Exclusive: Tests show billions of people globally are drinking water contaminated by plastic particles, with 83% of samples found to be polluted.

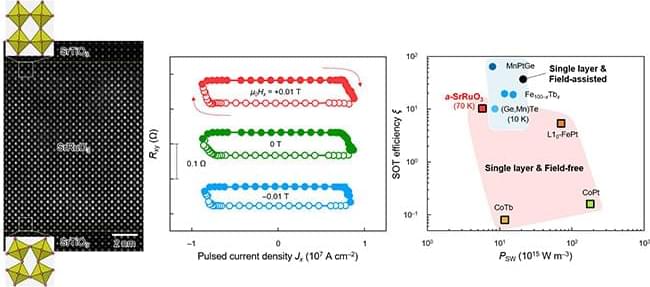

Like the flutter of a butterfly’s wings, sometimes small and minute changes can lead to big and unexpected results and changes in our lives. Recently, a team of researchers at Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) made a very small change to develop a material called “spin-orbit torque (SOT),” which is a hot topic in next-generation DRAM memory.

This research team, led by Professor Daesu Lee and Yongjoo Jo, a PhD candidate, from the Department of Physics and Professor Si-Young Choi from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at POSTECH, achieved highly efficient field-free (i.e. SOT magnetization switching that does not require the assistance of a magnetic field) SOT magnetization switching through atom-level control of composite oxides.

Their findings were recently published in Nano Letters (“Field-Free Spin–Orbit Torque Magnetization Switching in a Single-Phase Ferromagnetic and Spin Hall Oxide”).

Gaussian ray tracing: fast tracing of particle scenes.

Nicolas Moenne-Loccoz, Ashkan Mirzaei, Or Perel, Riccardo de Lutio, Janick Martinez Esturo, Gavriel State, Sanja Fidler, Nicholas Sharp, Zan Gojcic NVDIA 2024 https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.07090 https://radiancefields.com/3d-gaussian-ray–…

Today, things are taking an exciting step forward with the introduction of 3D Gaussian Ray Tracing (3DGRT).

Electrons inherently carry both spin and orbital angular momentum (i.e., properties that help to understand the rotating motions and behavior of particles). While some physicists and engineers have been trying to leverage the spin angular momentum of electrons to develop new technologies known as spintronics, these particles’ orbital momentum has so far been rarely considered.

Currently, generating an orbital current (i.e., a flow of orbital angular momentum) remains far more challenging than generating a spin current. Nonetheless, approaches to successfully leverage the orbital angular momentum of electrons could open the possibility for the development of a new class of devices called orbitronics.

Researchers at Keio University and Johannes Gutenberg University report the successful generation of an orbital current from magnetization dynamics, a phenomenon called orbital pumping. Their paper, published in Nature Electronics, outlines a promising approach that could allow engineers to develop new technologies leveraging the orbital angular momentum of electrons.

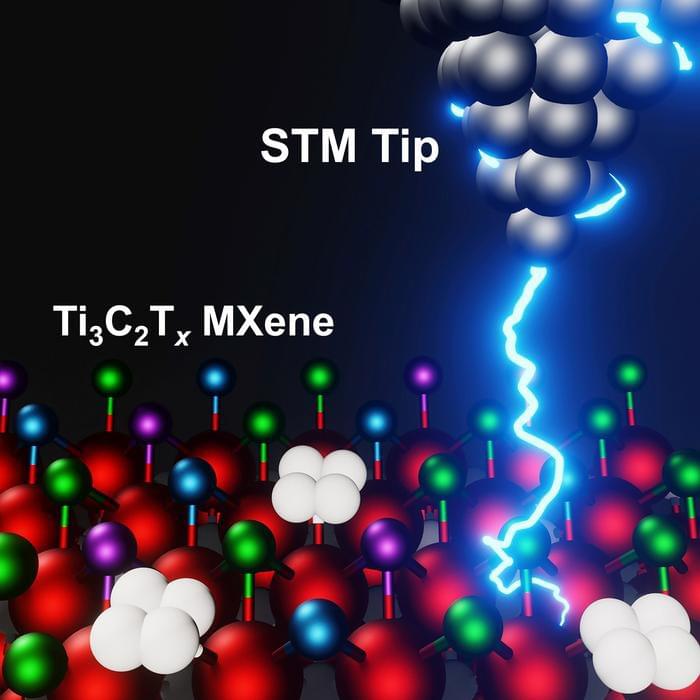

In the decade since their discovery at Drexel University, the family of two-dimensional materials called MXenes has shown a great deal of promise for applications ranging from water desalination and energy storage to electromagnetic shielding and telecommunications, among others. While researchers have long speculated about the genesis of their versatility, a recent study led by Drexel and the University of California, Los Angeles, has provided the first clear look at the surface chemical structure foundational to MXenes’ capabilities.

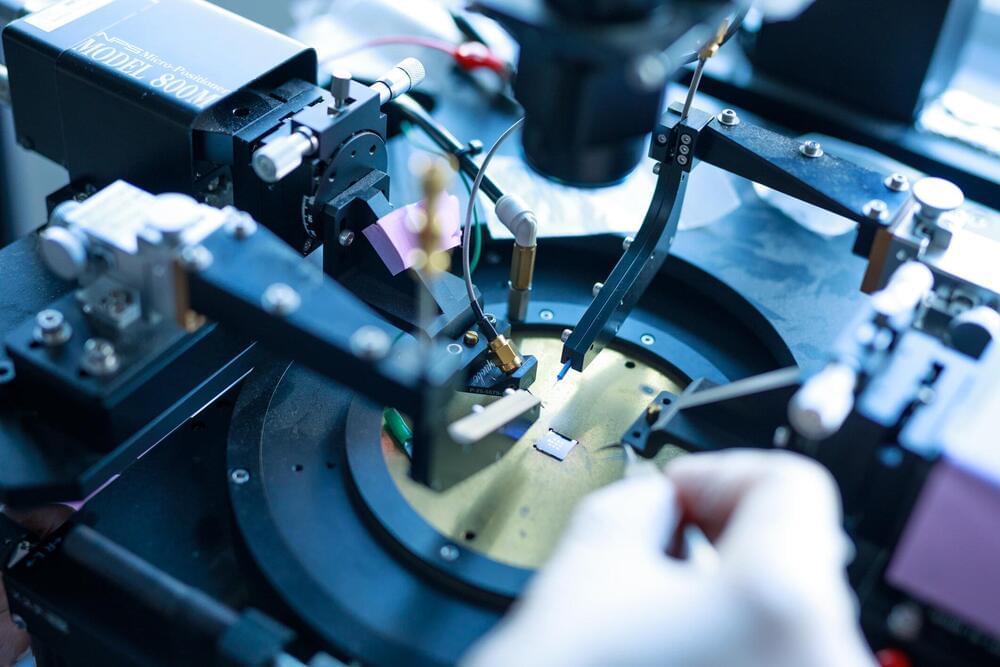

Using advanced imaging techniques, known as scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS), the team, which also includes researchers from California State University Northridge, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, mapped the electrochemical surface topography of the titanium carbide MXene — the most-studied and widely used member of the family.

Their findings, published in the 5th anniversary issue of the Cell Press journal Matter (“Atomic-scale investigations of Ti 3 C 2 Tx MXene surfaces”), will help to explain the range of properties exhibited by members of the MXene family and allow researchers to tailor new materials for specific applications.

Scientists have for the first time observed how atoms in magnesium oxide morph and melt under ultra-harsh conditions, providing new insights into this key mineral within Earth’s mantle that is known to influence planet formation.

High-energy laser experiments — which subjected tiny crystals of the mineral to the type of heat and pressure found deep inside a rocky planet’s mantle — suggest the compound could be the earliest mineral to solidify out of magma oceans in forming “super-Earth” exoplanets.

“Magnesium oxide could be the most important solid controlling the thermodynamics of young super-Earths,” said June Wicks, an assistant professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins University who led the research. “If it has this very high melting temperature, it would be the first solid to crystallize when a hot, rocky planet starts to cool down and its interior separates into a core and a mantle.”

So I serve a hundred years in one day…’- Joe Haldeman, 2011.

Robot Preachers Found To Undermine Religious Commitment ‘Tell me your torments,’ the Padre said, in an elderly voice marked with compassion. — Philip K. Dick, 1969.

Gaia — Why Stop With Just The Earth? ‘But the stars are only atoms in larger space, and in that larger space the star-atoms could combine to form living matter, thinking matter, couldn’t they?’ — Robert Castle, 1939.