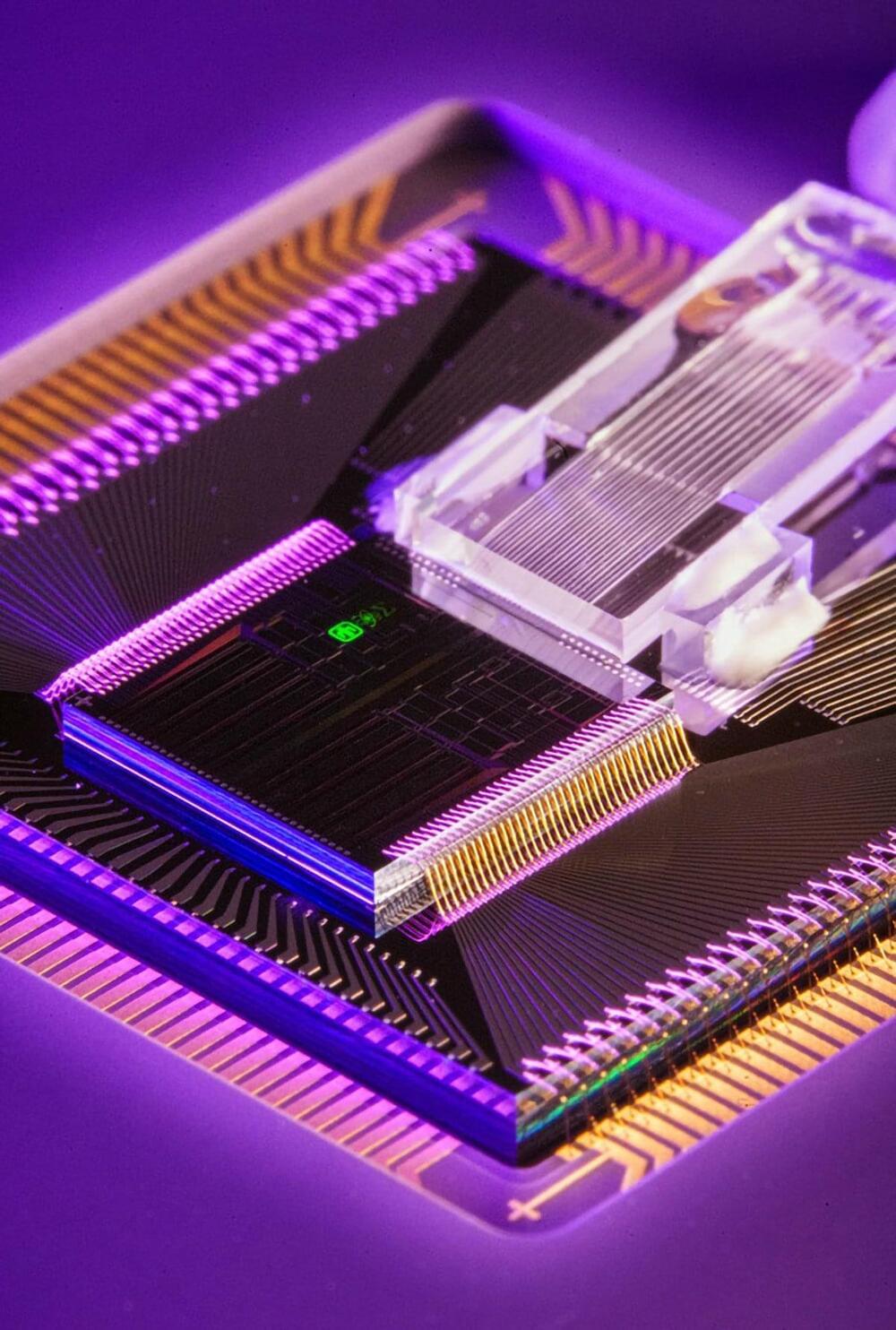

Innovative diode laser spectroscopy provides precise monitoring of the color changes in the sweeping laser at each moment, establishing new benchmarks for frequency metrology and practical applications.

Since the laser’s debut in the 1960s, laser spectroscopy has evolved into a crucial technique for investigating the intricate structures and behaviors of atoms and molecules. Advances in laser technology have significantly expanded its potential. Laser spectroscopy primarily consists of two key types: frequency comb-based laser spectroscopy and tunable continuous-wave (CW) laser spectroscopy.

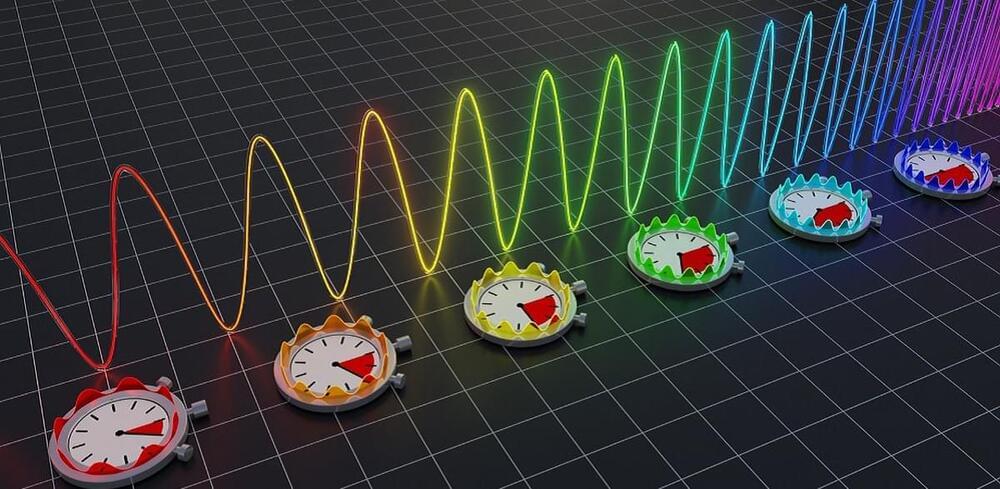

Comb-based laser spectroscopy enables extremely precise frequency measurements, with an accuracy of up to 18 digits. This remarkable precision led to a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2005 and has applications in optical clocks, gravity sensing, and the search for dark matter. Frequency combs also enable high-precision, high-speed broadband spectroscopy because they combine large bandwidth with high spectral resolution.