Helen Edwards was a particle physicist who led the design and construction of the Tevatron, a machine built to probe deeper into the atom than anyone had gone before.

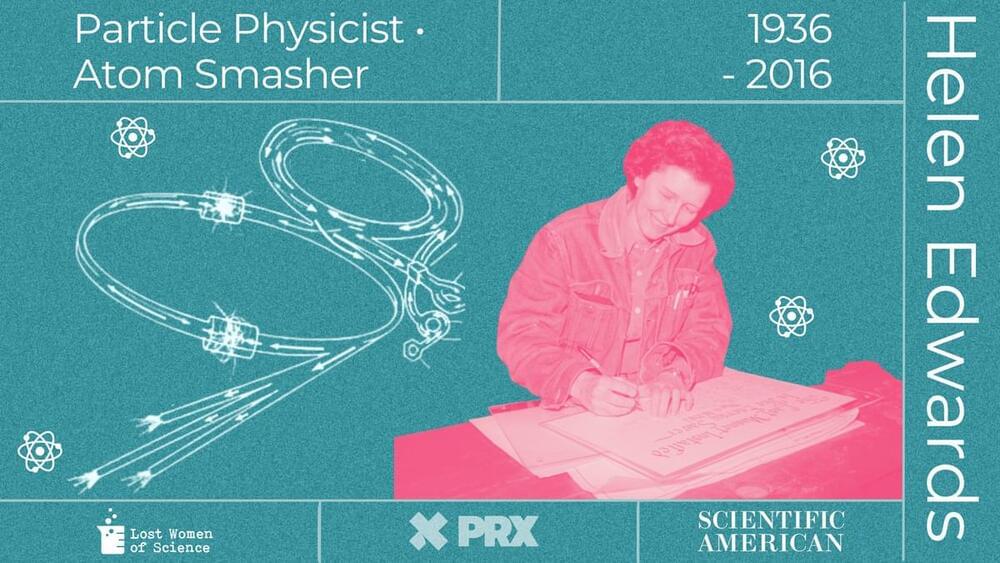

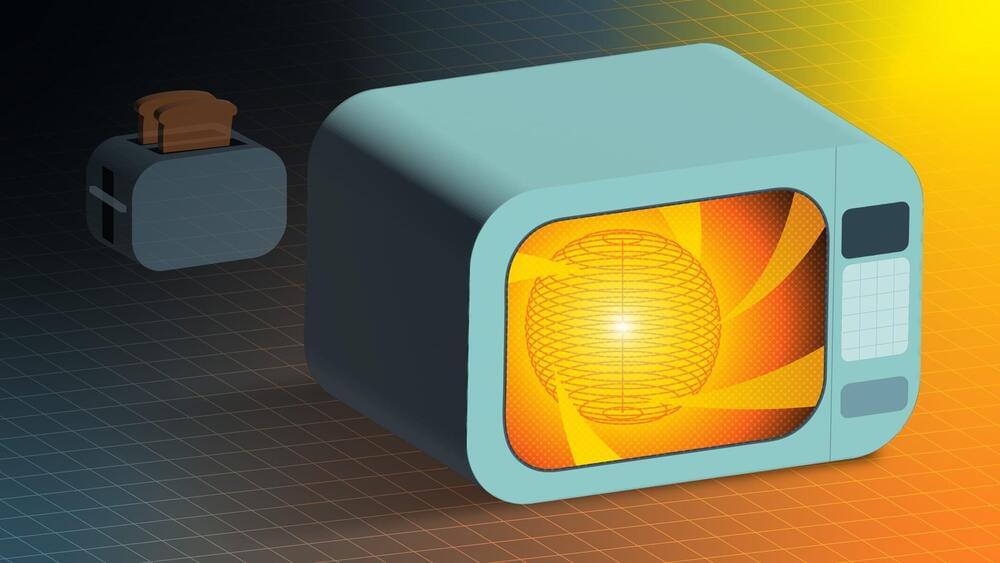

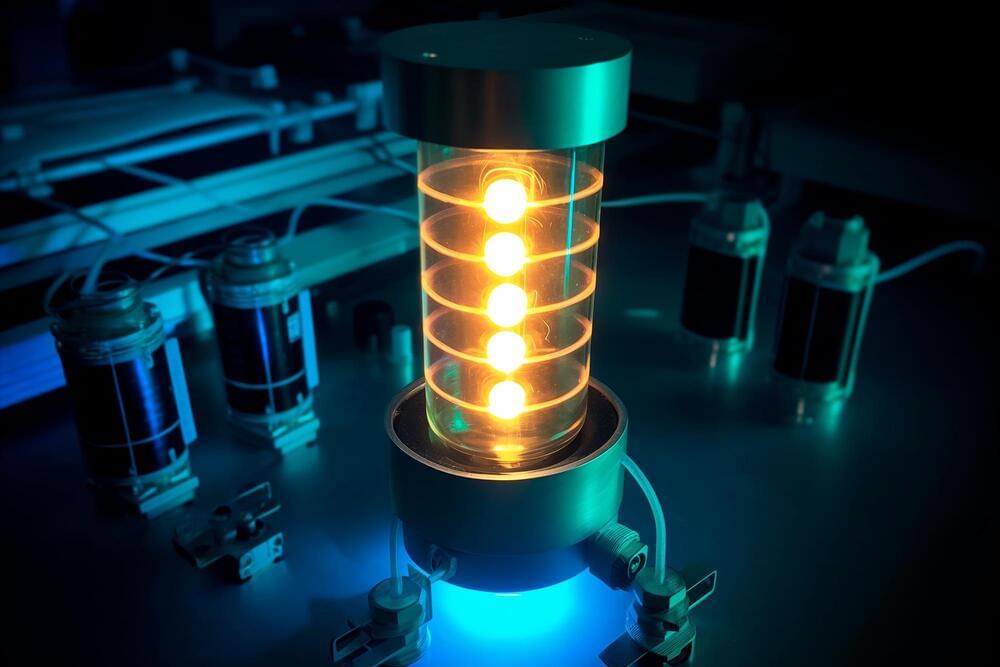

Some experts believe that the future of fusion in the U.S. may be found in compact, spherical fusion vessels. A smaller tokamak is seen as a potentially more economical solution for fusion energy. The challenge lies in fitting all necessary components into a limited space. Recent research indicates that removing one key component used to heat the plasma could create the additional space required.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), the private company Tokamak Energy, and Kyushu University in Japan have proposed a design for a compact, spherical fusion pilot plant that heats the plasma using only microwaves. Typically, spherical tokamaks also use a massive coil of copper wire called a solenoid, located near the center of the vessel, to heat the plasma. Neutral beam injection, which involves applying beams of uncharged particles to the plasma, is often used as well. But much like a tiny kitchen is easier to design if it has fewer appliances, it would be simpler and more economical to make a compact tokamak if it has fewer heating systems.

The new approach eliminates ohmic heating, which is the same heating that happens in a toaster and is standard in tokamaks. “A compact, spherical tokamak plasma looks like a cored apple with a relatively small core, so one does not have the space for an ohmic heating coil,” said Masayuki Ono, a principal research physicist at PPPL and lead author of the paper detailing the new research. “If we don’t have to include an ohmic heating coil, we can probably design a machine that is easier and cheaper to build.”

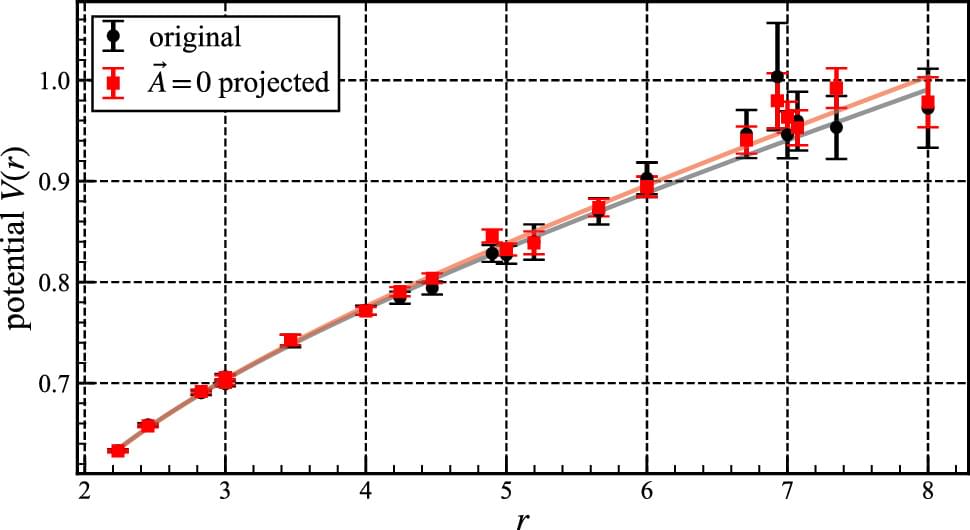

Aiming at the relation between QCD and the quark model, we consider projections of gauge configurations generated in quenched lattice QCD simulations in the Coulomb gauge on a 16 $$^{\textrm{3}}$$3 $$\mathrm \times $$ × 32, $$\mathrm \beta $$ β = 6.0 lattice. First, we focus on a fact that the static quark-antiquark potential is independent of spatial gauge fields. We explicitly confirm this by performing $$\textbf{A}$$ A = 0 projection, where spatial gauge fields are all set to zero. We also apply the $$\textbf{A}$$ A = 0 projection to light hadron masses and find that nucleon and delta baryon masses are almost degenerate, suggesting vanishing of the color-magnetic interactions.

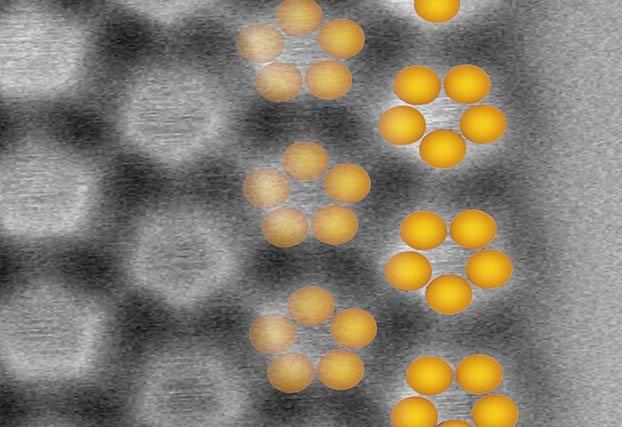

Phosphorus is an exciting element: It is essential for the survival of organisms and promises numerous electronic applications. With this in mind, researchers at the University of Basel have synthesized two-dimensional layers containing rings of five phosphorus atoms (phosphorus pentamers (cyclo-P5)) on a silver surface.

For the first time, they have been able to investigate their electronic properties using combined atomic force and scanning tunneling spectroscopy. They found that the atomic phosphorus pentamer layer retains its semiconductor properties and forms a special electronic interface where the layer joins the silver surface (p-type semiconductor-metal Schottky junction).

This shows that phosphorus pentamers on the silver surface fulfill a basic requirement for applications in field-effect transistors, diodes or solar cells, as recently reported by the research team in the scientific journal Nature Communications (“Probing charge redistribution at the interface of self-assembled cyclo-P5 pentamers on Ag(111)”).

CU Boulder scientists have found how ions move in tiny pores, potentially improving energy storage in devices like supercapacitors. Their research updates Kirchhoff’s law, with significant implications for energy storage in vehicles and power grids.

Imagine if your dead laptop or phone could be charged in a minute, or if an electric car could be fully powered in just 10 minutes. While this isn’t possible yet, new research by a team of scientists at CU Boulder could potentially make these advances a reality.

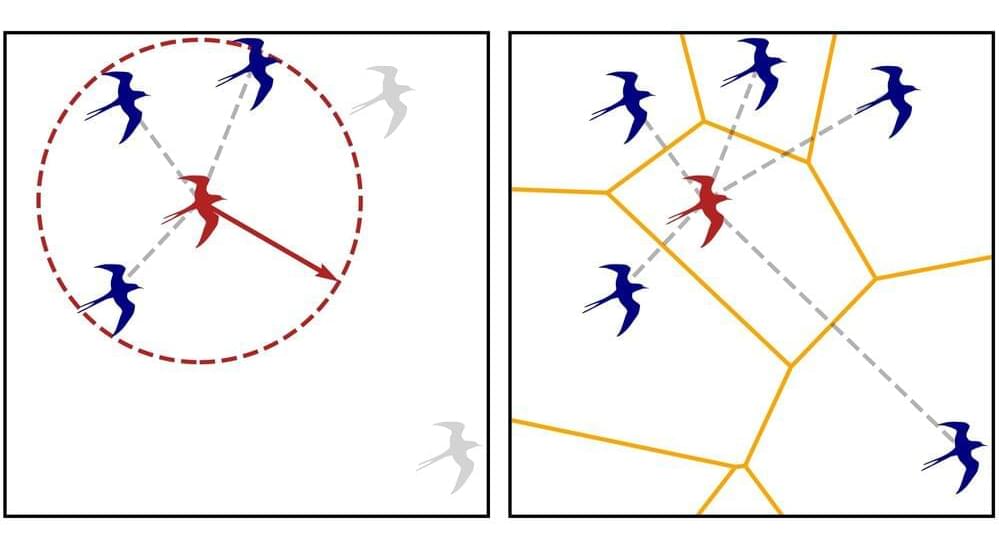

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers in Ankur Gupta’s lab discovered how tiny charged particles, called ions, move within a complex network of minuscule pores. The breakthrough could lead to the development of more efficient energy storage devices, such as supercapacitors, said Gupta, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering.

Using a laser to raise the energy state of an atom ’s nucleus, known as excitation, can lead to the development of the most precise atomic clocks. This process has been challenging because the electrons surrounding the nucleus are highly reactive to light, necessitating more light to affect the nucleus. UCLA physicists have overcome this by bonding the electrons with fluorine in a transparent crystal, allowing them to excite the neutrons in a thorium atom’s nucleus using a moderate amount of laser light. This achievement paves the way for significantly more accurate measurements of time, gravity, and other fields, far surpassing the current accuracy levels provided by atomic electrons.

For almost half a century, physicists have envisioned the possibilities that could arise from elevating the energy state of an atom’s nucleus with a laser. This breakthrough would enable the replacement of current atomic clocks with a nuclear clock, the most accurate timekeeping device ever conceived. Such precision would revolutionize fields like deep space navigation and communication.

It would also allow scientists to measure precisely whether the fundamental constants of nature are, in fact, really constant or merely appear to be because we have not yet measured them precisely enough.

“We can rewind to a previous scene or skip several scenes ahead.”

An worldwide team of scientists claims to have found a means to speed up, slow down, and even reverse the clock of a given system by taking use of the peculiar qualities of the quantum universe, as reported by Spanish newspaper El País.

The scientists from the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the University of Vienna presented their findings in six separate papers. The basic principles of physics do not transfer intuitively onto the subatomic world, which is made up of quantum particles known as qubits, which can exist in several states at the same time, a phenomenon known as quantum entanglement.