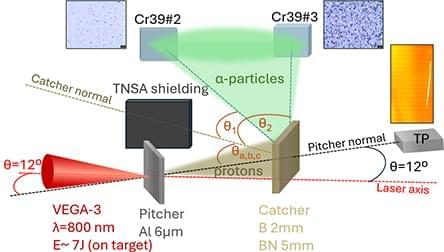

The majority of studies on laser-driven proton–boron nuclear reaction is based on the measurement of α-particles with solid-state nuclear tracks detector (Cr39). However, Cr39’s interpretation is difficult due to the presence of several other accelerated particles which can bias the analysis. Furthermore, in some laser irradiation geometries, cross-checking measurements are almost impossible. In this case, numerical simulations can play a very important role in supporting the experimental analysis. In our work, we exploited different laser irradiation schemes (pitcher–catcher and direct irradiation) during the same experimental campaign, and we performed numerical analysis, allowing to obtain conclusive results on laser-driven proton–boron reactions. A direct comparison of the two laser irradiation schemes, using the same laser parameters is presented.