Entire atoms have been put through a classic quantum experiment for the first time and the breakthrough could lead to better detectors for picking up the gravitational waves that ripple across the universe.

By Alex Wilkins

Entire atoms have been put through a classic quantum experiment for the first time and the breakthrough could lead to better detectors for picking up the gravitational waves that ripple across the universe.

By Alex Wilkins

When quantum electrodynamics, the quantum field theory of electrons and photons, was being developed after World War II, one of the major challenges for theorists was calculating a value for the Lamb shift, the energy of a photon resulting from an electron transitioning from one hydrogen hyperfine energy level to another.

The effect was first detected by Willis Lamb and Robert Retherford in 1947, with the emitted photon having a frequency of 1,000 megahertz, corresponding to a photon wavelength of 30 cm and an energy of 4 millionths of an electronvolt—right on the lower edge of the microwave spectrum. It came when the one electron of the hydrogen atom transitioned from the 2P1/2 energy level to the 2S1/2 level. (The leftmost number is the principal quantum number, much like the discrete but increasing circular orbits of the Bohr atom.)

Conventional quantum mechanics didn’t have such transitions, and Dirac’s relativistic Schrödinger equation (naturally called the Dirac equation) did not have such a hyperfine transition either, because the shift is a consequence of interactions with the vacuum, and Dirac’s vacuum was a “sea” that did not interact with real particles.

Special multi-layer mirrors guide the light through plates called masks, which hold the intricate patterns of the integrated circuits for semiconductor wafers. The light projects the pattern onto a photoresist layer that is etched away to leave the integrated circuits on the chip, according to a press release by LLNL.

The project also aims to investigate the primary hypothesis that the energy efficiency of existing EUV lithography sources for semiconductor production can be improved with technology developed for the novel petawatt-class BAT laser, which uses thulium-doped yttrium lithium fluoride (Tm: YLF) as the gain medium through which the power and intensity of laser beams are increased, as per the release.

Scientists have planned to conduct a demonstration pairing the compact high-rep-rate BAT laser with technologies that generate sources of EUV light using shaped nanosecond pulses and high-energy x-rays and particles using ultrashort sub-picosecond pulses.

What is the deepest level of reality? In this Quanta explainer, Vijay Balasubramanian, a physicist at the University of Pennsylvania, takes us on a journey through space-time to investigate what it’s made of, why it’s failing us, and where physics can go next.

Explore black holes, holograms, “alien algebra,” and more space-time geometry: https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-un…

00:00 — The Planck length, an intro to space-time.

1:23 — Descartes and Newton investigate space and time.

2:04 — Einstein’s special relativity.

2:32 — The geometry of space-time and the manifold.

3:16 — Einstein’s general relativity: space-time in four dimensions.

3:35 — The mathematical curvature of space-time.

4:57 — Einstein’s field equation.

6:04 — Singularities: where general relativity fails.

6:50 — Quantum mechanics (amplitudes, entanglement, Schrödinger equation)

8:32 — The problem of quantum gravity.

9:38 — Applying quantum mechanics to our manifold.

10:36 — Why particle accelerators can’t test quantum gravity.

11:28 — Is there something deeper than space-time?

11:45 — Hawking and Bekenstein discover black holes have entropy.

13:54 — The holographic principle.

14:49 — AdS/CFT duality.

16:06 — Space-time may emerge from entanglement.

17:44 — The path to quantum gravity.

——-

VISIT our website: https://www.quantamagazine.org.

LIKE us on Facebook: / quantanews.

FOLLOW us Twitter: / quantamagazine.

Quanta Magazine is an editorially independent publication supported by the Simons Foundation: https://www.simonsfoundation.org

At first glance, it might seem obvious that atoms touch each other, especially when you consider the material world around us. From the objects we handle to the materials we utilize, everything indeed appears very solid. However, the question of whether atoms actually “touch” as we understand it on a human level is far more intricate than it might seem. In fact, the answer hinges on how we define “touch,” a concept that shifts significantly at the atomic scale.

At the human scale, “touch” generally refers to the meeting of well-defined surfaces. For instance, when you place a glass on a table, you might say the two objects are touching because their outer surfaces overlap. However, at the atomic scale, this notion of contact becomes much more ambiguous. An atom is neither a solid object nor an entity with a clear boundary. It consists of a central nucleus made up of protons and neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of constantly moving electrons. This unpredictable movement means the electron cloud does not create a fixed and defined surface.

To understand what contact means between atoms, one must look into the internal structure of these particles and the interactions occurring between their electrons. Each atom is made up of a central nucleus surrounded by an electron cloud, which isn’t located at a specific spot but occupies areas known as orbitals. These orbitals are regions of probability where it’s more or less likely to find an electron at any given time. Their shape and organization vary depending on the chemical element of the atom, giving each type of atom unique characteristics.

Tachyons, the hypothetical particles that travel faster than light, have long fascinated scientists and enthusiasts. In this video, we explore how the McGinty Equation (MEQ) serves as a groundbreaking tool in understanding these elusive particles. Delve into the world of quantum mechanics, fractal geometry, and gravity as we uncover the potential of tachyons to revolutionize science and technology. From their intriguing properties, such as imaginary mass and energy reduction at high speeds, to their implications for faster-than-light communication and interstellar exploration, this video is a journey into uncharted territories of physics.

We also discuss the quest to detect tachyons, innovative experimental methods, and the role of MEQ in guiding researchers. Could tachyons be the key to unlocking new dimensions, explaining dark matter and energy, or understanding the origins of the universe? Join us in this deep dive into the unknown and discover the potential future of tachyon research.

#Tachyons #McGintyEquation #QuantumMechanics #FractalGeometry #FasterThanLight #ImaginaryMass #QuantumPhysics #AdvancedPhysics #TachyonResearch #LightSpeedPhysics #QuantumFieldTheory #ScientificDiscovery #SpaceTime #InterstellarTravel #DarkMatter #DarkEnergy #FasterThanLightCommunication #PhysicsBreakthrough #CosmicMysteries #HypotheticalParticles

NASA has been monitoring a strange anomaly in Earth’s magnetic field: a giant region of lower magnetic intensity in the skies above the planet, stretching out between South America and southwest Africa.

This vast, developing phenomenon, called the South Atlantic Anomaly, has intrigued and concerned scientists for years, and perhaps none more so than NASA researchers.

The space agency’s satellites and spacecraft are particularly vulnerable to the weakened magnetic field strength within the anomaly, and the resulting exposure to charged particles from the Sun.

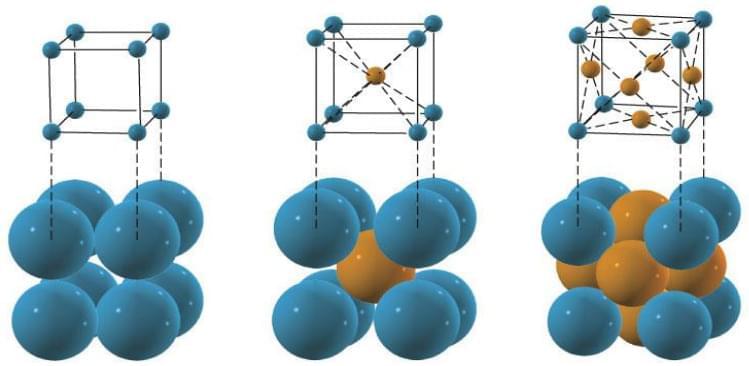

All solids have a crystal structure that shows the spatial arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in the lattice. These crystal structures are often determined by a method known as X-ray diffraction technique (XRD).

These crystal structures play an import role in determining many physical properties such as the electronic band structure, cleavage and explains many of their physical and chemical properties.

This article aims to discuss an approach to identify these structures by various machine learning and deep learning methods. It demonstrates how supervised machine learning and deep learning approaches and help in determining various crystal structures of solids.

The 21st century faces an unprecedented energy challenge that demands innovative solutions. This video explores Zero Point Energy (ZPE), a groundbreaking concept rooted in quantum mechanics that promises limitless, clean, and sustainable power. Learn how the quantum vacuum—long considered empty—is teeming with virtual particles and untapped energy potential. From understanding the Casimir effect to leveraging advanced technologies like fractal energy collectors and quantum batteries, this video details how ZPE could revolutionize industries, mitigate climate change, and empower underserved communities. Dive into the science, challenges, and global implications of a ZPE-powered future.

#ZeroPointEnergy #CleanEnergy #QuantumVacuum #Sustainability #EnergyInnovation #ZPE #QuantumMechanics #RenewableEnergy #GreenTech #CasimirEffect #QuantumEnergy #EnergySustainability #ClimateSolutions #FractalEnergy #QuantumBatteries #AdvancedTechnology #LimitlessEnergy #Nanotechnology #FutureOfEnergy #CleanPower

With so much fascinating research going on in quantum science and technology, it’s hard to pick just a handful of highlights. Fun, but hard. Research on entanglement-based imaging and quantum error correction both appear in Physics World’s list of 2024’s top 10 breakthroughs, but beyond that, here are a few other achievements worth remembering as we head into 2025 – the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology.

Quantum sensing

In July, physicists at Germany’s Forschungszentrum Jülich and Korea’s IBS Center for Quantum Nanoscience (QNS) reported that they had fabricated a quantum sensor that can detect the electric and magnetic fields of individual atoms. The sensor consists of a molecule containing an unpaired electron (a molecular spin) that the physicists attached to the tip of a scanning-tunnelling microscope. They then used it to measure the magnetic and electric dipole fields emanating from a single iron atom and a silver dimer on a gold substrate.