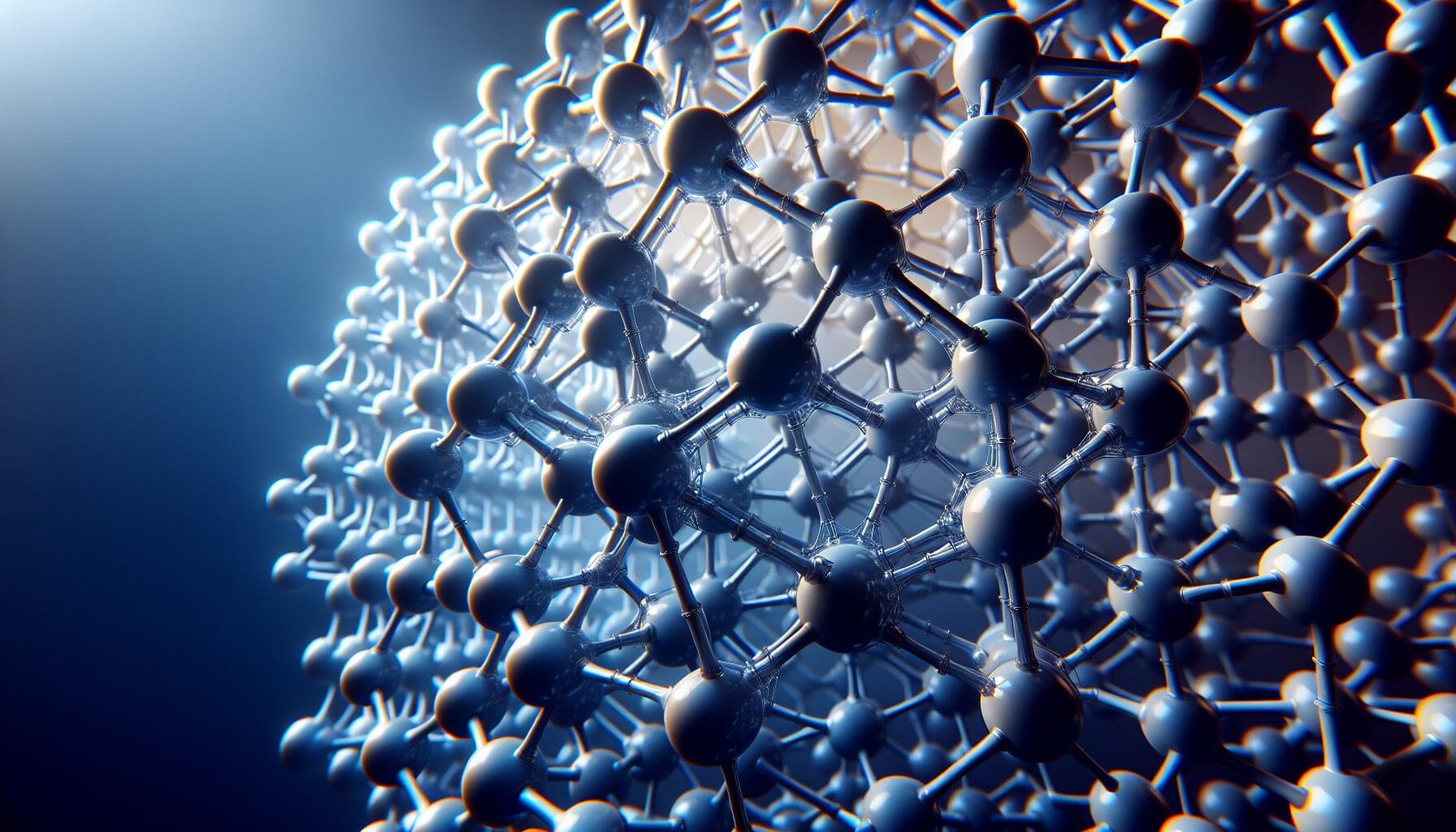

Can copper be turned into gold? For centuries, alchemists pursued this dream, unaware that such a transformation requires a nuclear reaction. In contrast, graphite—the material found in pencil tips—and diamond are both composed entirely of carbon atoms; the key difference lies in how these atoms are arranged. Converting graphite into diamond requires extreme temperatures and pressures to break and reform chemical bonds, making the process impractical.

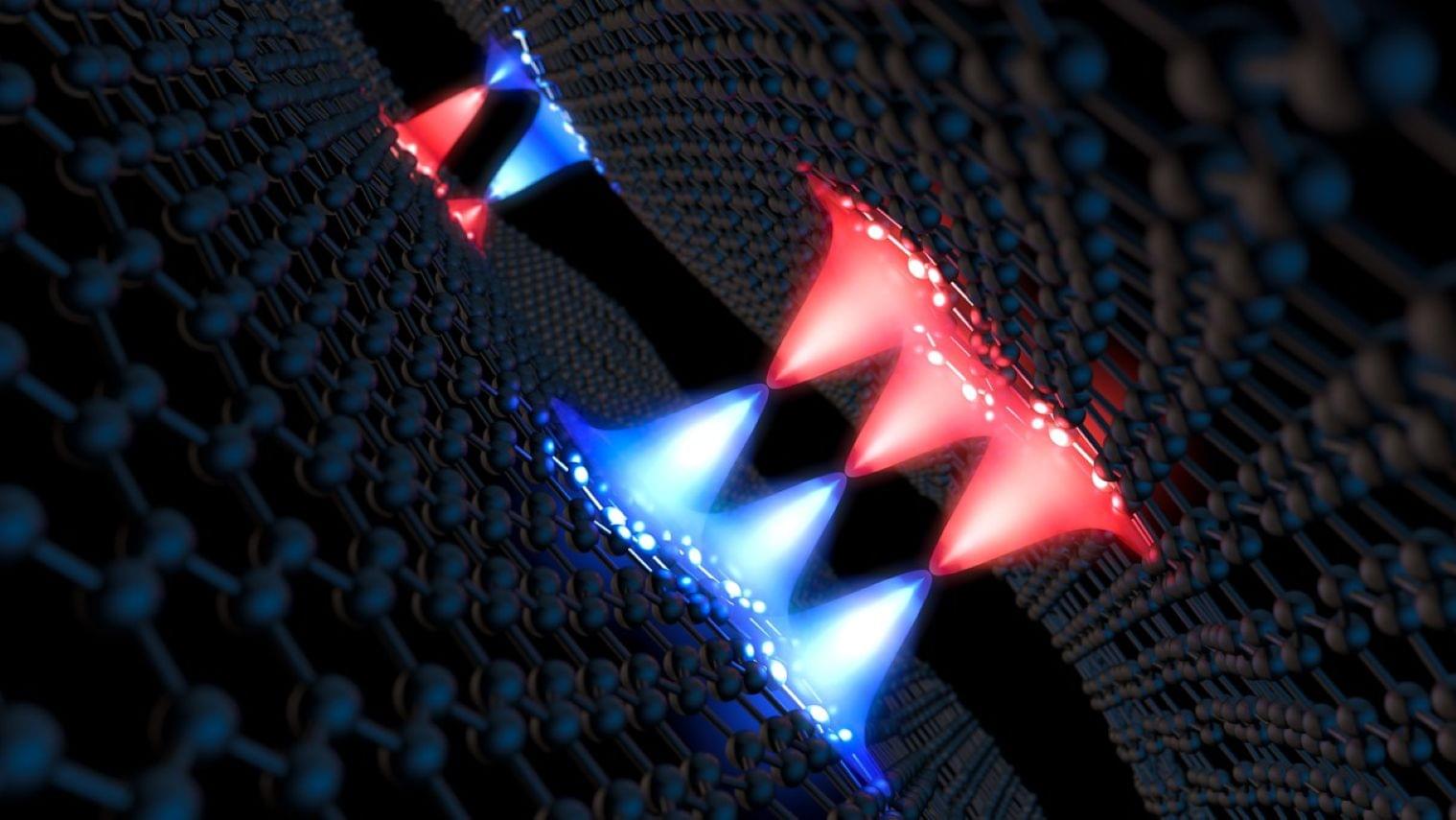

A more feasible transformation, according to Prof. Moshe Ben Shalom, head of the Quantum Layered Matter Group at Tel Aviv University, involves reconfiguring the atomic layers of graphite by shifting them against relatively weak van der Waals forces. This study, led by Prof. Ben Shalom and Ph.D. students Maayan Vizner Stern and Simon Salleh Atri, all from the Raymond & Beverly Sackler School of Physics & Astronomy at Tel Aviv University, was recently published in the journal Nature Review Physics.

While this method won’t create diamonds, if the switching process is fast and efficient enough, it could serve as a tiny electronic memory unit. In this case, the value of these newly engineered “polytype” materials could surpass that of both diamonds and gold.