A search for particles’ most paradoxical quantum states led researchers to construct a 37-dimensional experiment.

A search for particles’ most paradoxical quantum states led researchers to construct a 37-dimensional experiment.

Quantum networks require quantum nodes that are built using quantum dots.

However, a new study impressively solves these challenges. The study authors successfully used 13,000 nuclear spins in a gallium arsenide (GaAs) quantum dot system to create a scalable quantum register.

Quantum networks require quantum nodes that are built using quantum dots — tiny particles, much smaller than a human hair, which can trap and control electrons, and store quantum information.

Quantum dots are valued for their ability to emit single photons because single-photon sources are key requirements for secure quantum communication and quantum computing applications.

Everyone has their favourite example of a trick that reliably gets a certain job done, even if they don’t really understand why. Back in the day, it might have been slapping the top of your television set when the picture went fuzzy. Today, it might be turning your computer off and on again.

Quantum mechanics — the most successful and important theory in modern physics — is like that. It works wonderfully, explaining things from lasers and chemistry to the Higgs boson and the stability of matter. But physicists don’t know why. Or at least, if some of us think we know why, most others don’t agree.

Graphene is an allotrope of carbon in the form of a single layer of atoms in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice in which one atom forms each vertex. It is the basic structural element of other allotropes of carbon, including graphite, charcoal, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes. In proportion to its thickness, it is about 100 times stronger than the strongest steel.

What do eyes, quantum collapse, and photon emission have in common?

While experimenting with a simple particle simulation, an unexpected phenomenon emerged that bridges multiple realms of physics and perception.

The simulation, designed to model particles moving in toroidal orbits while attracting each other, spontaneously developed a striking pattern: a perfectly centered emission of particles perpendicular to the toroid’s plane, resembling both an eye and a quantum emission event.

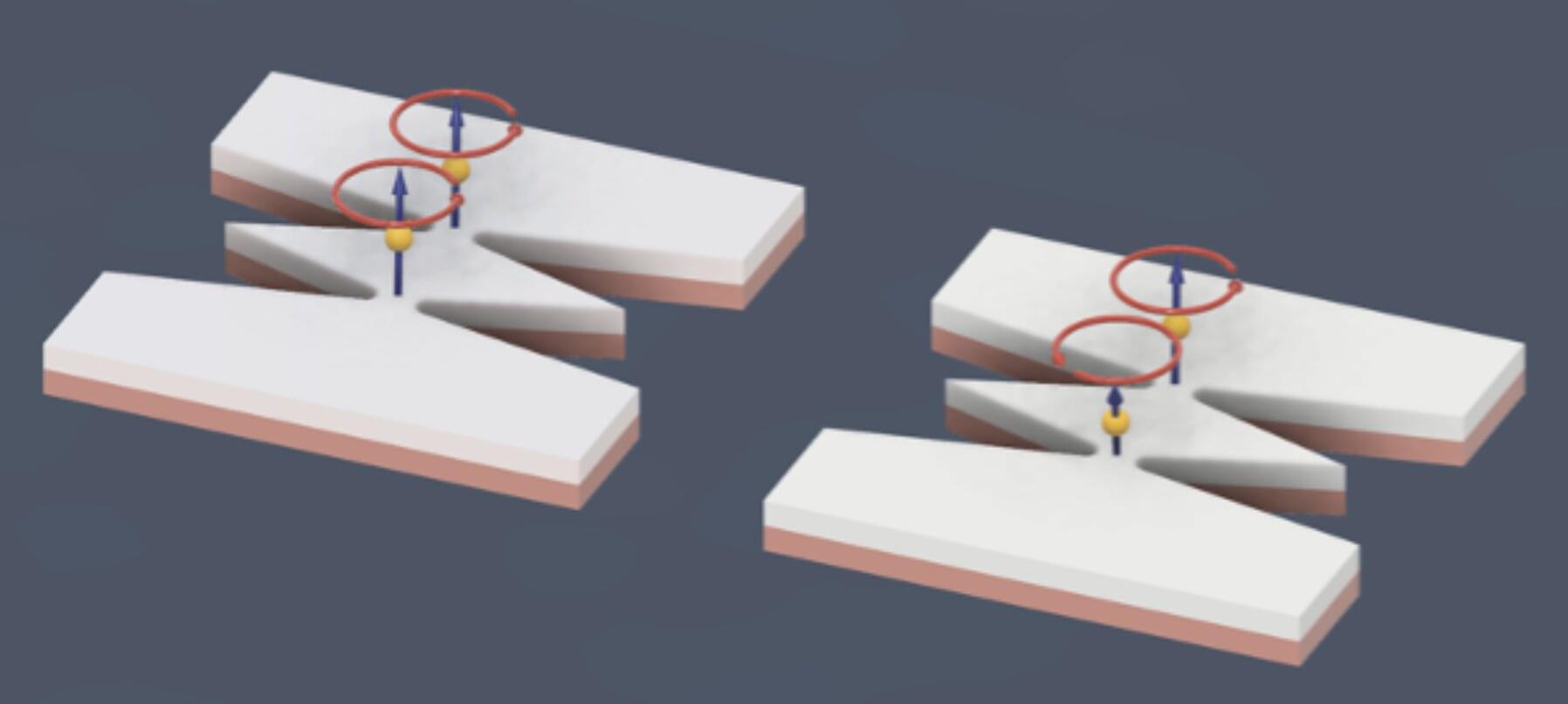

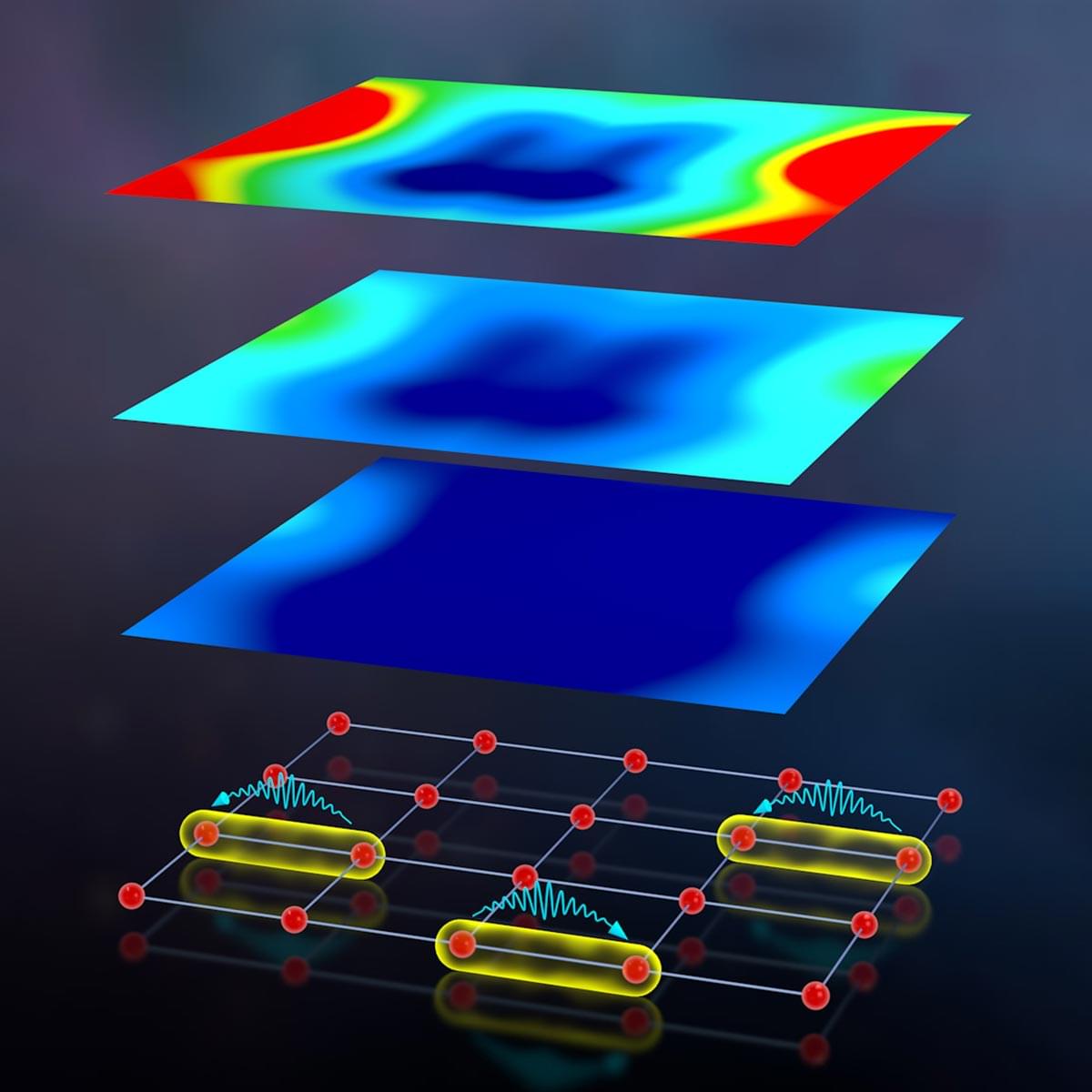

Spin Hall nano-oscillators (SHNOs) are nanoscale spintronic devices that convert direct current into high-frequency microwave signals through spin wave auto-oscillations. This is a type of nonlinear magnetization oscillations that are self-sustained without the need for a periodic external force.

Theoretical and simulation studies found that propagating spin-wave modes, in which spin waves move across materials instead of being confined to the auto-oscillation region, can promote the coupling between SHNOs.

This coupling may in turn be harnessed to adjust the timing of oscillations in these devices, which could be advantageous for the development of neuromorphic computing systems and other spintronic devices.

A groundbreaking discovery by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) has challenged a long-standing rule in organic chemistry known as Bredt’s Rule. Established nearly a century ago, this rule stated that certain types of specific organic molecules could not be synthesized due to their instability. UCLA’s team’s findings open the door to new molecular structures that were previously deemed unattainable, potentially revolutionizing fields such as pharmaceutical research.

To grasp the significance of this breakthrough, it’s helpful to first understand some basics of organic chemistry. Organic chemistry primarily deals with molecules made of carbon, such as those found in living organisms. Among these, certain molecules known as olefins or alkenes feature double bonds between two carbon atoms. These double bonds create a specific geometry: the atoms and atom groups attached to them are generally in the same plane, making these structures fairly rigid.

In 1924, German chemist Julius Bredt formulated a rule regarding certain molecular structures called bridged bicyclic molecules. These molecules have a complex structure with multiple rings sharing common atoms, akin to two intertwined bracelet loops. Bredt’s Rule dictates that these molecules cannot have a double bond at a position known as the bridgehead, where the two rings meet. The rule is based on geometric reasons: a double bond at the bridgehead would create such significant structural strain that the molecule would become unstable or even impossible to synthesize.

Dangerous solar blast detected at Mars by Chinese Orbiter in new episode of Robots In Space!🇨🇳🟠.

Join aerospace engineer Mike DiVerde as he breaks down groundbreaking research on Mars radiation from multiple space missions. This comprehensive analysis combines data from Tianwen-1, MAVEN, ExoMars, and the Curiosity rover to understand the dangerous Solar Energetic Particles affecting Mars. Learn why radiation protection is crucial for future Mars colonization and astronaut safety and discover how space weather impacts potential Mars habitats. DiVerde explains complex space science concepts in an accessible way, drawing from recent research that highlights the challenges of keeping humans safe on Mars. Essential viewing for anyone interested in Mars exploration and the future of human space missions.

Have you ever looked up at the night sky and wondered what you’re not seeing? The skies may be full of invisible “boson stars” that are made of an exotic form of matter that does not shine.

We strongly suspect that the universe is full of dark matter, which makes up around 25% of all the mass and energy in the cosmos. But while circumstantial evidence abounds and we believe that dark matter is some sort of undiscovered particle, we don’t have any direct evidence of such a particle.

Researchers are exploring multi-level atomic interactions to enhance quantum entanglement. Using metastable states in strontium, they demonstrate how photon.

A photon is a particle of light. It is the basic unit of light and other electromagnetic radiation, and is responsible for the electromagnetic force, one of the four fundamental forces of nature. Photons have no mass, but they do have energy and momentum. They travel at the speed of light in a vacuum, and can have different wavelengths, which correspond to different colors of light. Photons can also have different energies, which correspond to different frequencies of light.