In the annals of scientific inquiry, few endeavors have been as audacious as the attempt to bridge the chasm between the tangible and the intangible, the empirical and the experiential. The declassification of the 1983 U.S. Army Intelligence report, “Analysis and Assessment of The Gateway Process,” offers a compelling case study in this regard. Authored by Lieutenant Colonel Wayne M. McDonnell, the report delves into altered states of consciousness, suggesting that human consciousness may transcend the physical plane, potentially supporting concepts akin to reincarnation. This proposition invites us to explore the intersection of infodynamics — the study of information dynamics within physical systems — and phenomena traditionally deemed spiritual, under the premise that all such phenomena are rooted in the natural order.

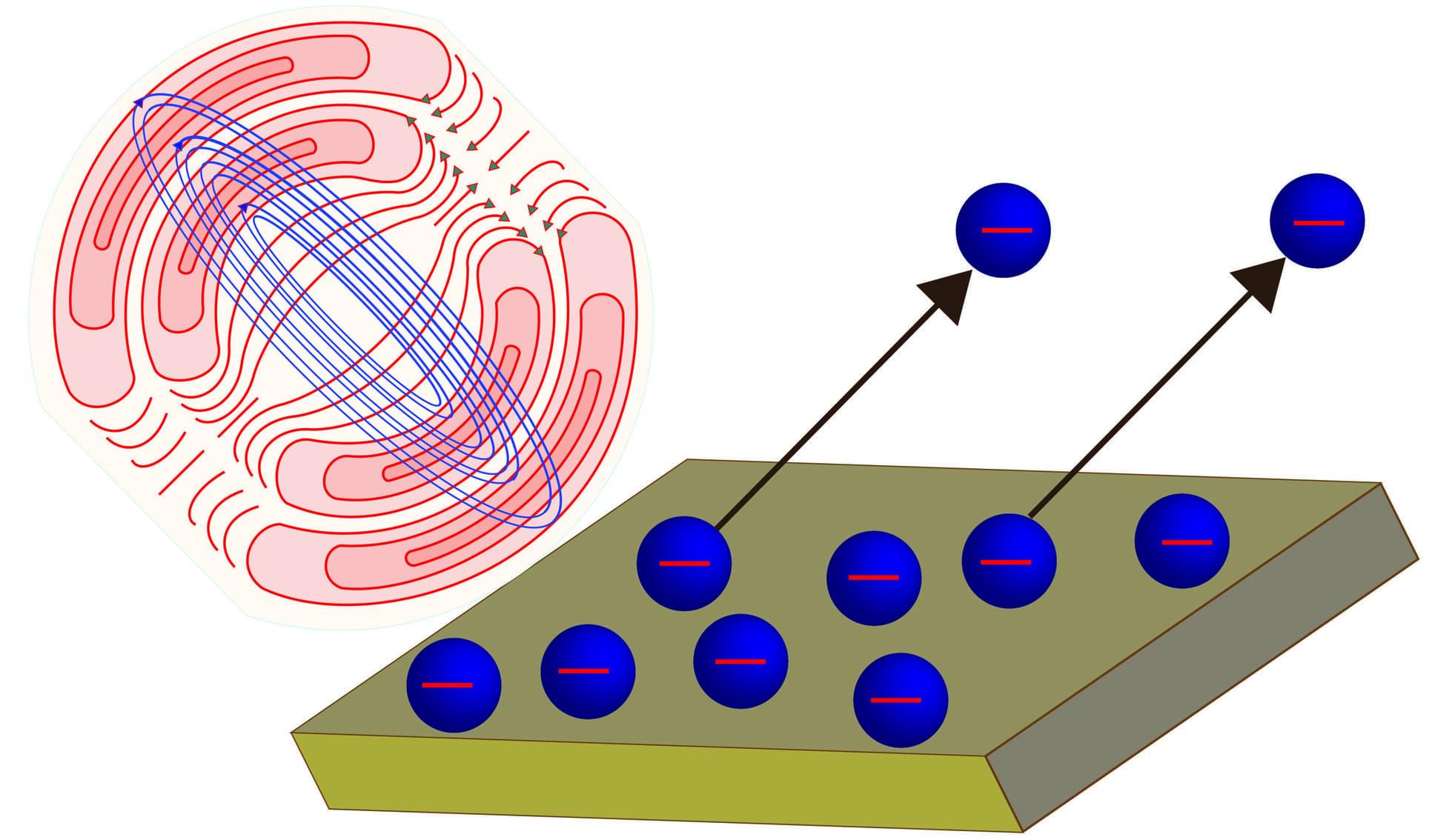

At the heart of this exploration lies the principle that information, much like energy, is conserved within the universe. This concept is reminiscent of the first law of thermodynamics, which asserts that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed. In the realm of information theory, this translates to the idea that information persists, undergoing transformations but never facing annihilation. This perspective aligns with the notion that consciousness, as a form of information, may continue beyond the cessation of its current physical embodiment.

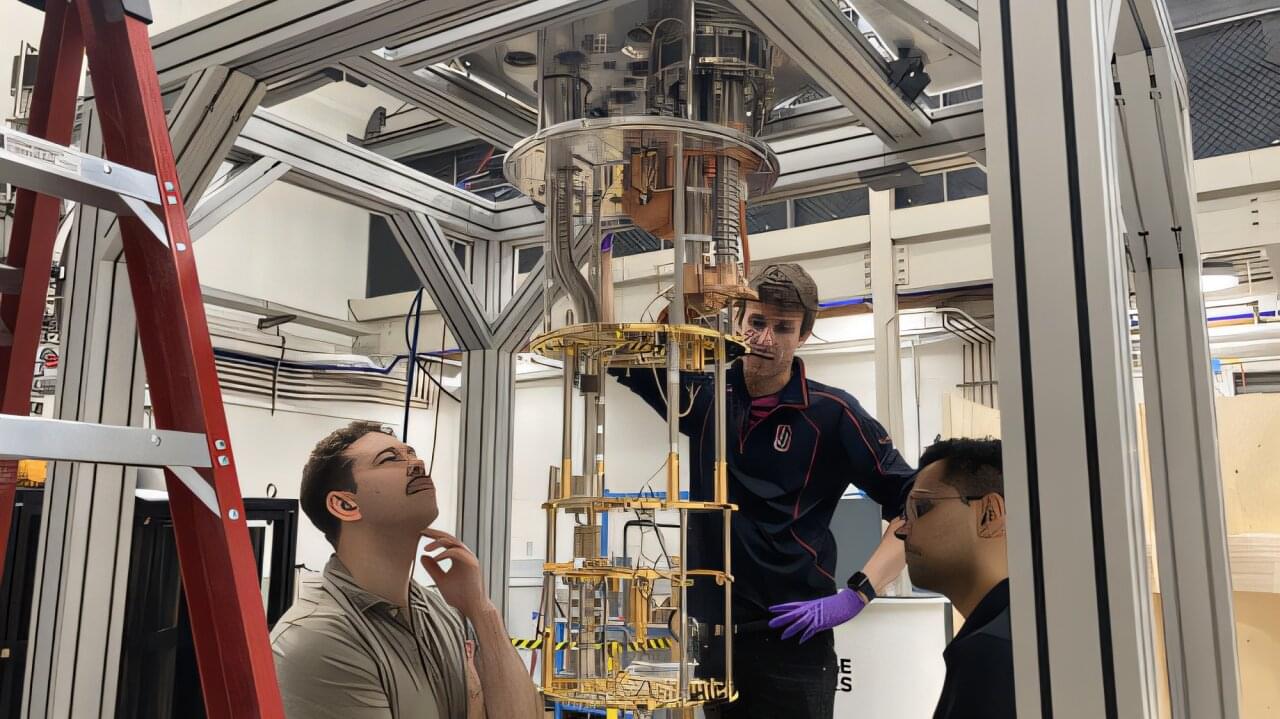

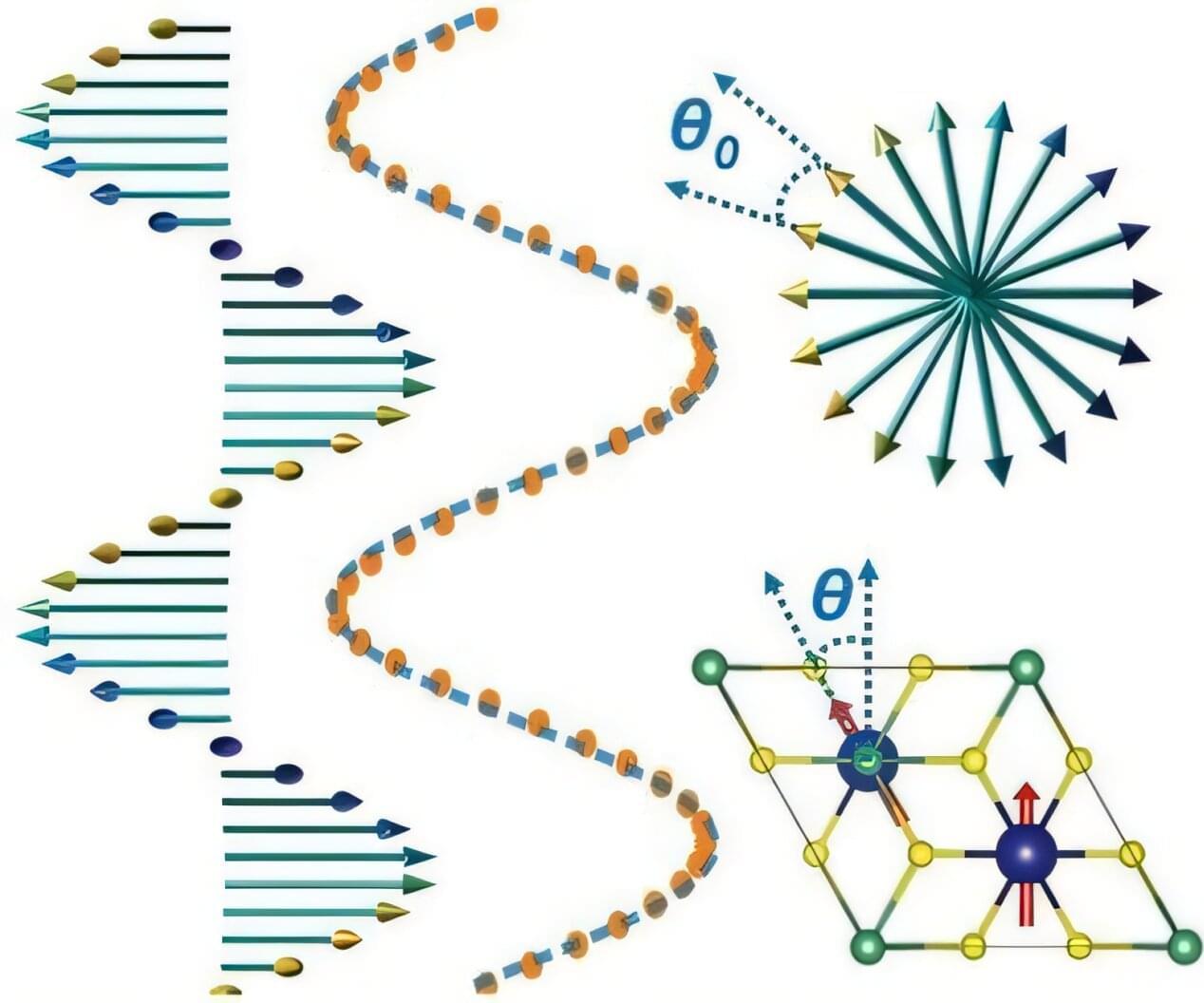

Quantum mechanics further enriches this discourse. The phenomenon of quantum entanglement, wherein particles become interconnected in such a way that the state of one instantaneously influences the state of another, regardless of the spatial separation, challenges our classical understanding of locality and separability. This non-locality suggests a deeply interconnected fabric of reality, where information is not confined to a singular point in space or time. Such a framework provides a plausible basis for understanding how consciousness, as an informational construct, could transcend individual physical forms, offering a naturalistic foundation for phenomena like reincarnation.