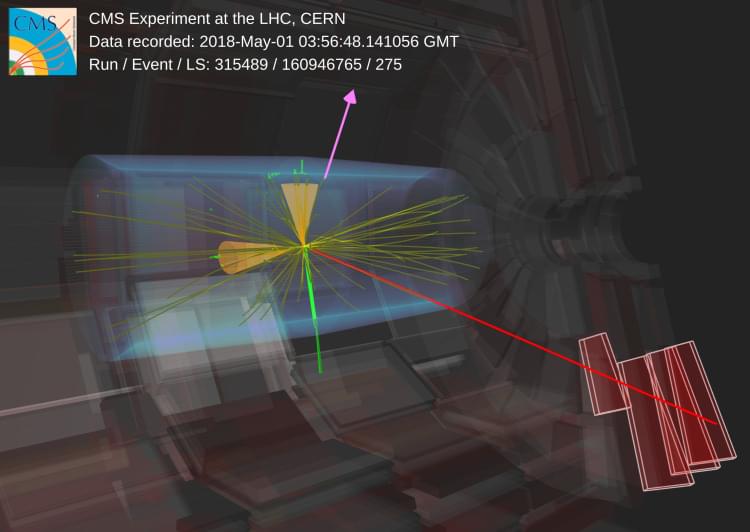

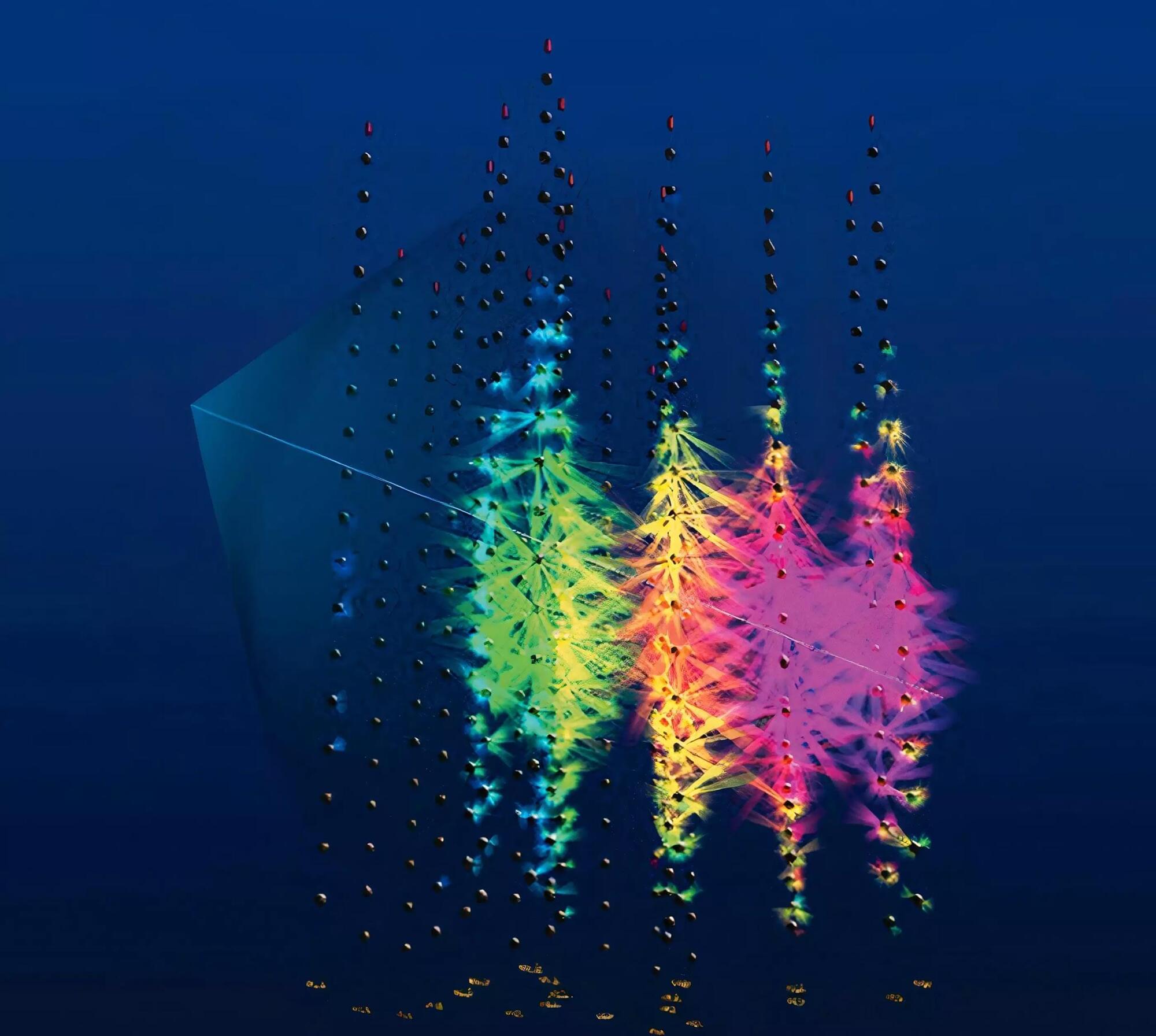

Quantum gravity is one of the biggest unresolved and challenging problems in physics, as it seeks to reconcile quantum mechanics, which governs the microscopic world, and general relativity, which describes the macroscopic world of gravity and space-time.

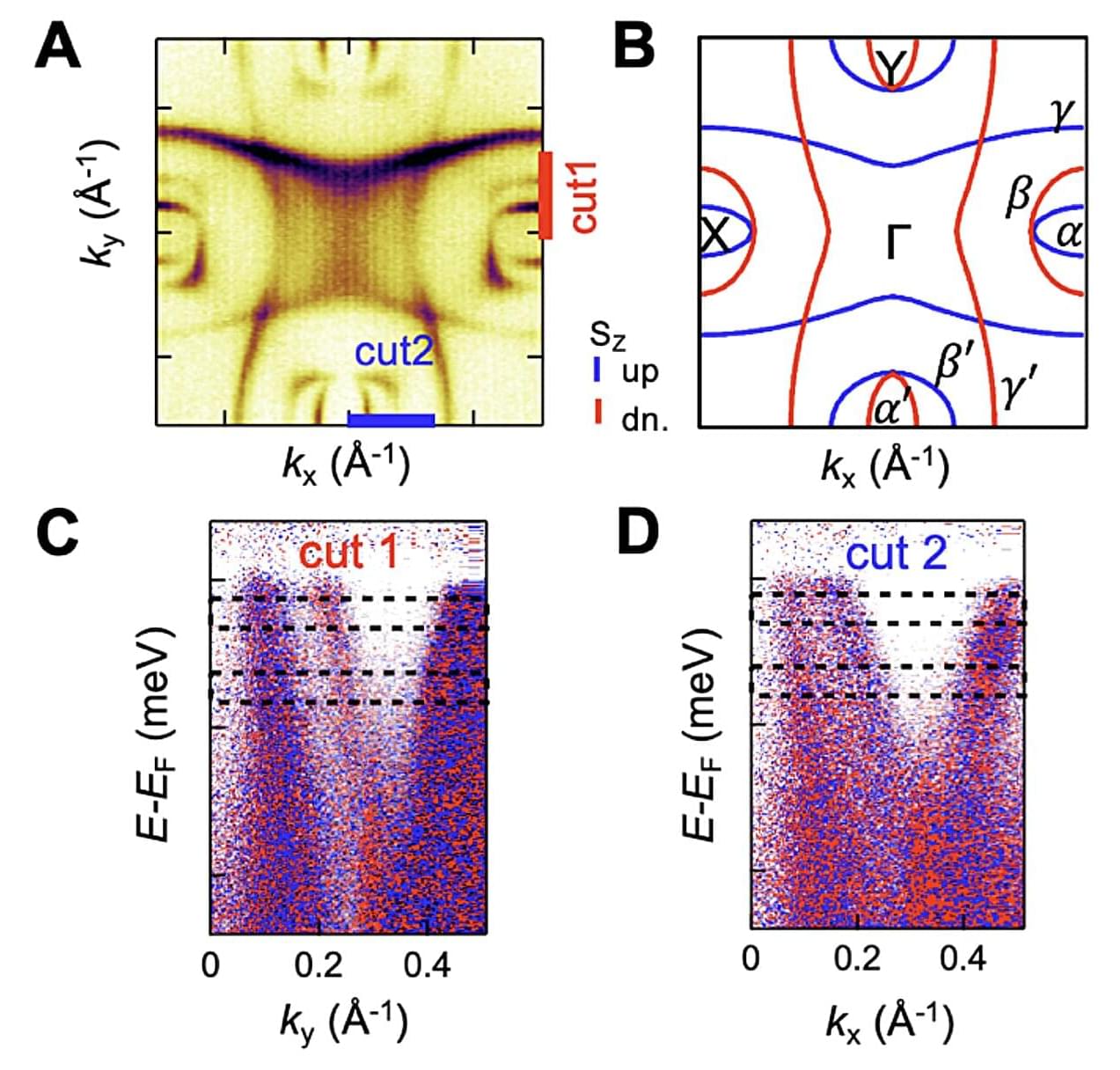

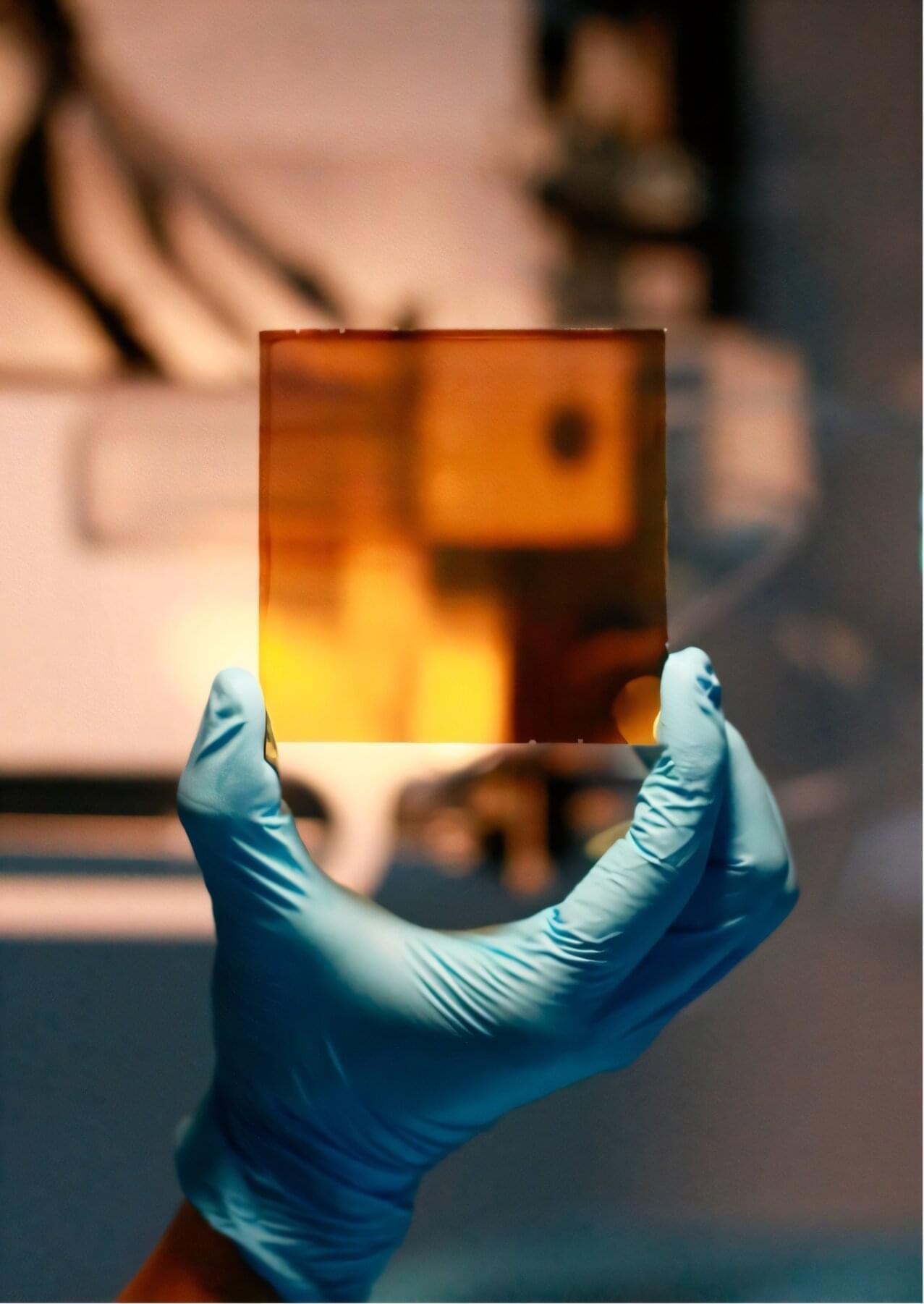

Efforts to understand quantum gravity have been focused almost entirely at the theoretical level, but Monika Schleier-Smith at Stanford University has been exploring a novel experimental approach — trying to create quantum gravity from scratch. Using laser-cooled clouds of atoms, she is testing the idea that gravity might be an emergent phenomenon arising from quantum entanglement.

In this episode of The Joy of Why podcast, Schleier-Smith discusses the thinking behind what she admits is a high-risk, high-reward approach, and how her experiments could provide important insights about entanglement and quantum mechanical systems even if the end goal of simulating quantum gravity is never achieved.