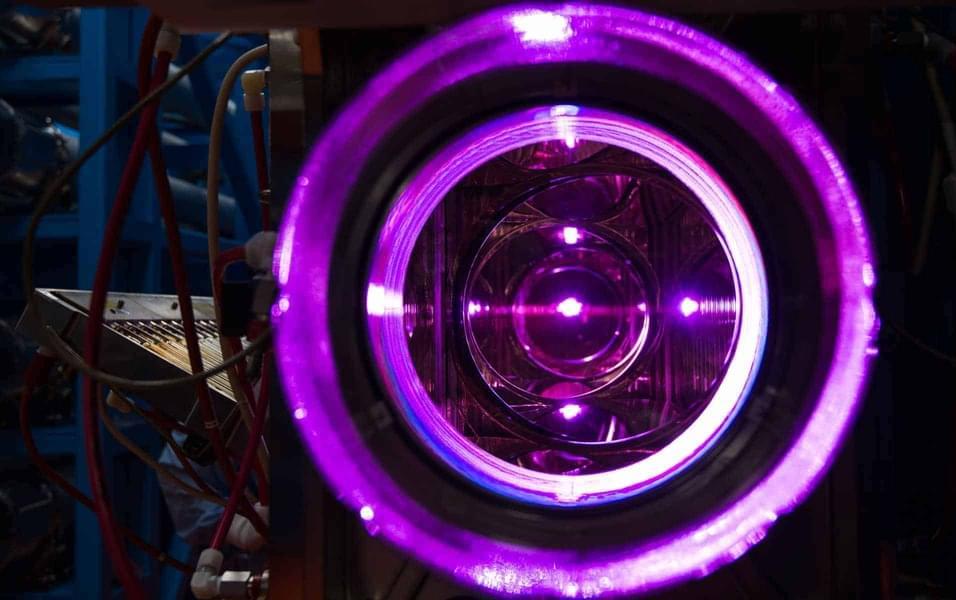

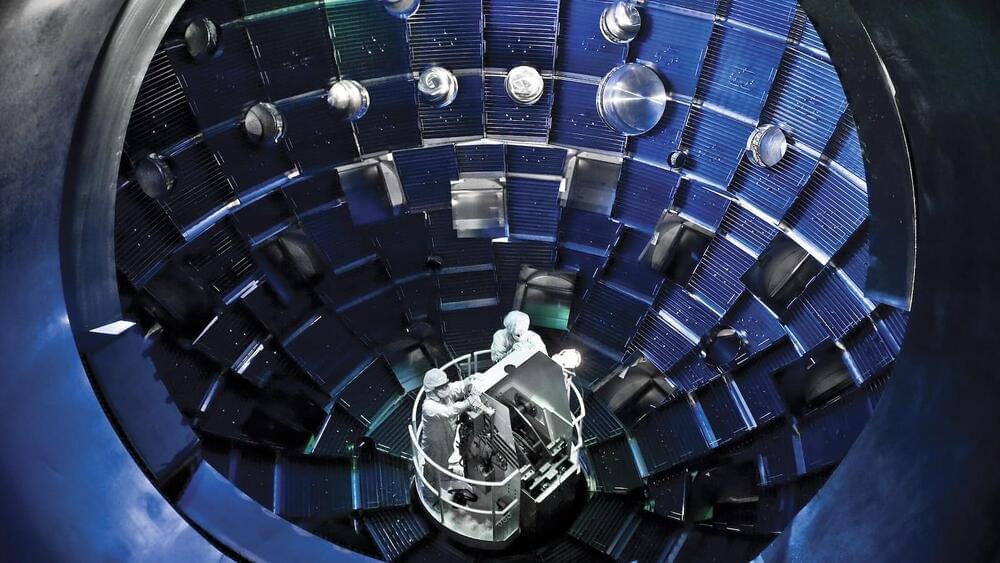

FUTABA, Japan (AP) — At Japan’s tsunami-wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, giant blue pipes have been constructed to bring in torrents of seawater to dilute treated, radioactive water under a plan to discharge it gradually into the Pacific Ocean.

Workers were making final preparations as Associated Press journalists received a rare opportunity Friday to get a look at key equipment and facilities for the release, expected in coming weeks or months.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has looked at Japan’s wastewater-release plan and said it would cause negligible radioactivity in the sea and no effect on neighboring countries. But the plans continue to draw strong protest and no starting date has been set.