University of California, Irvine scientists have expanded on a longstanding model governing the mechanics behind slip banding, a process that produces strain marks in metals under compression, gaining a new understanding of the behavior of advanced materials critical to energy systems, space exploration and nuclear applications.

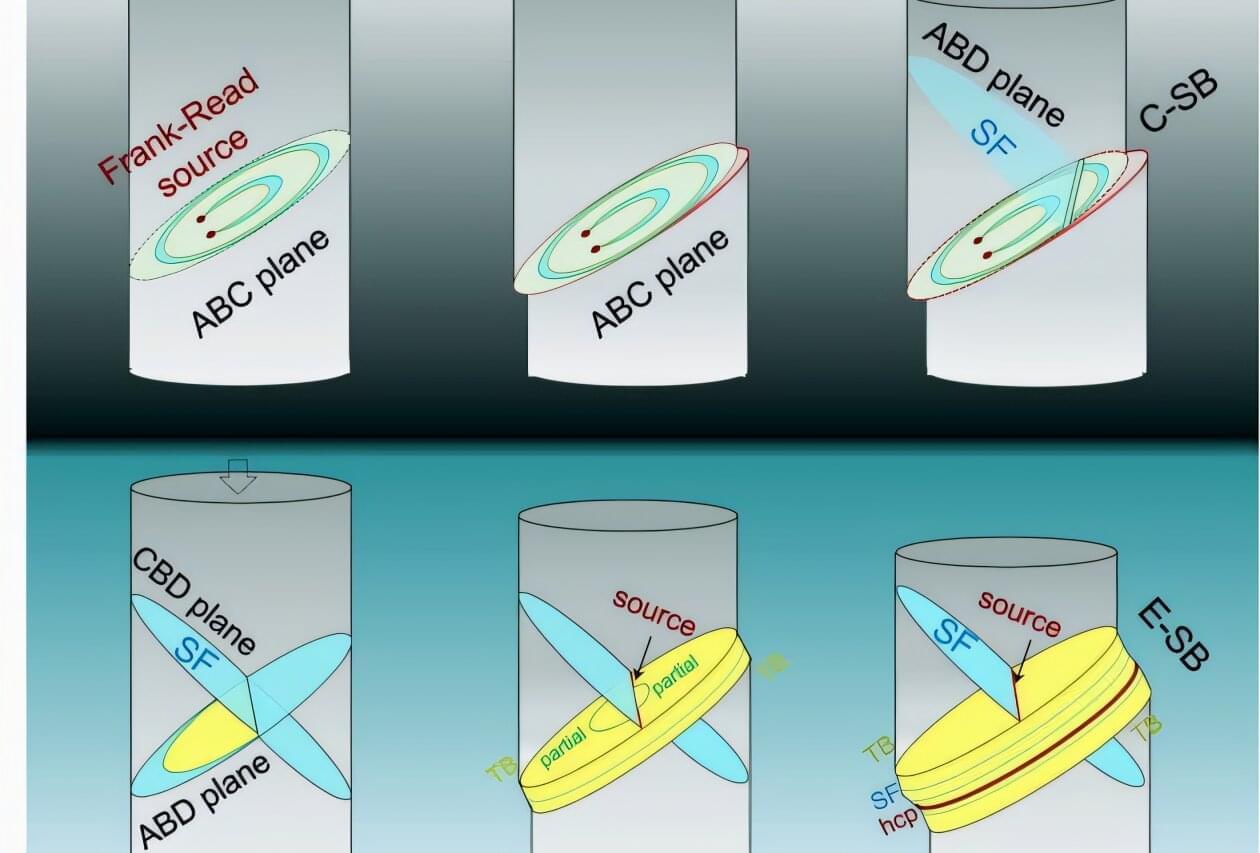

In a paper published recently in Nature Communications, researchers in UC Irvine’s Samueli School of Engineering report the discovery of extended slip bands—a finding that challenges the classic model developed in the 1950s by physicists Charles Frank and Thornton Read.

While the Frank–Read theory attributes slip band formation to continuous dislocation multiplication at active sources, the UC Irvine team found that extended slip bands emerge from source deactivation followed by the dynamic activation of new dislocation sources.