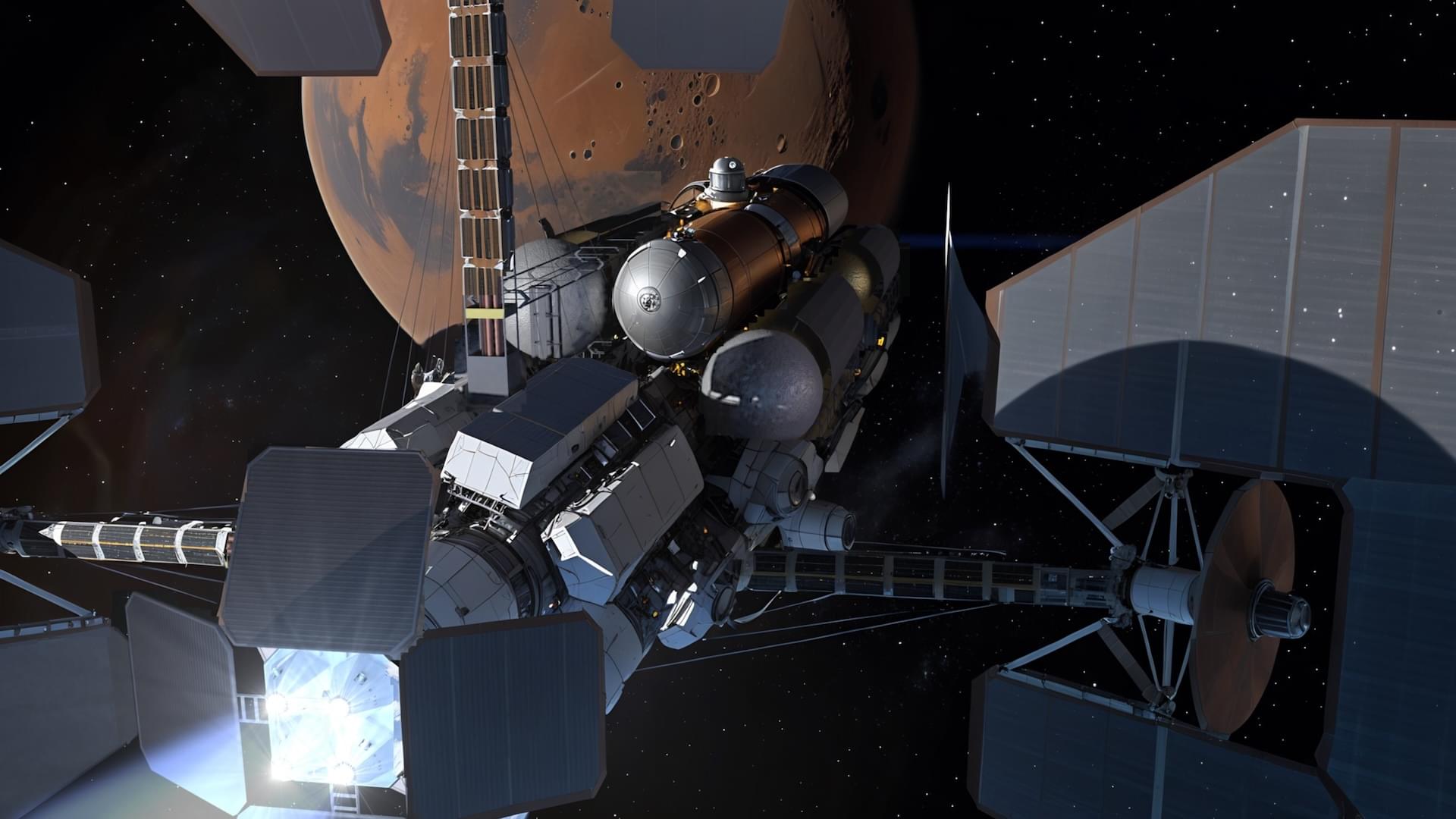

Nuclear electric rockets could fly to Mars in as little as 45 days. Space firm SpaceNukes is developing the reactor to make this possible.

Join our free newsletter for weekly updates on the latest innovations improving our lives and shaping our future, and don’t miss this cool list of easy ways to help yourself while helping the planet.

First appeared on The Cool Down.

IN A NUTSHELL 🌕 Interlune, a Seattle-based startup, plans to extract helium-3 from the moon, aiming to revolutionize clean energy and quantum computing. 🚀 The company has developed a prototype excavator capable of digging up to ten feet into lunar soil, refining helium-3 directly on the moon for efficiency. 🔋 Helium-3 offers potential for nuclear

High-energy particles or gamma rays are usually needed to kick an atomic nucleus up to a higher-energy state. But last year, scientists excited thorium-229 nuclei with just laser light (see Viewpoint: Shedding Light on the Thorium-229 Nuclear Clock Isomer). Laser-excited nuclei could be useful for making precise timekeepers and sensitive quantum sensors. And now, Wolfram Ratzinger at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and his colleagues have shown how these nuclei also provide a way to detect certain speculative particles that may constitute dark matter [1].

Several models of dark matter involve axions or other extremely light bosons. Thanks to their lightness, these particles would have to be abundant—so much so that they would collectively behave like a classical field, oscillating at a frequency proportional to their mass. The particles’ interactions with the building blocks of nuclei—quarks and gluons—would cause various nuclear properties to oscillate at that same frequency. Among those properties is the energy of the photon emitted by an excited thorium-229 nucleus. Crucially, the oscillations in that energy are predicted to be much more pronounced, and therefore easier to detect, than those in other properties.

Ratzinger and his colleagues conducted the first-ever search for these oscillations in a previously reported spectrum of light emitted by excited thorium-229 nuclei. Finding no oscillations, the researchers set upper limits on the coupling strength of ultralight dark matter particles to quarks and gluons for particles ranging in mass from 10–20 to 10–13 eV. These limits are less stringent than those obtained through other means, but the team anticipates that ongoing and future experiments could set much stronger and possibly decisive constraints.

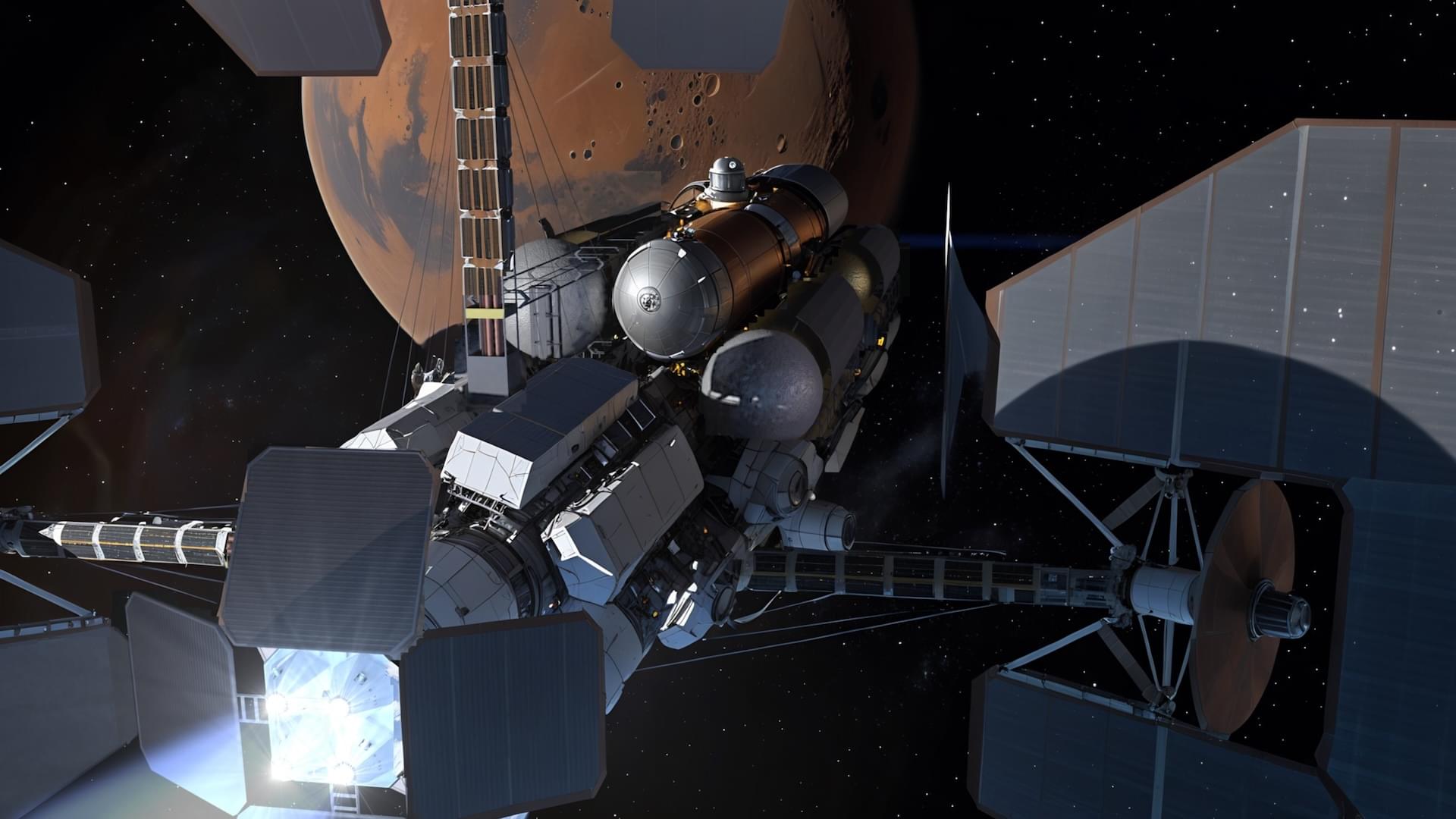

A team of chemists, materials scientists and engineers affiliated with several institutions in China, working with a colleague from Taiwan, has developed a new way to remove uranium from seawater that is much more efficient than other methods. Their paper is published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

The current method for obtaining uranium for use in nuclear power plants is mining it from the ground. Canada, Kazakhstan and Australia are currently the largest producers of uranium, accounting for nearly 70% of global production. Other countries such as the U.S., China and Russia would like to overcome their reliance on foreign providers of the radioactive element, and have been looking for ways to efficiently extract it from seawater.

The world’s oceans have far more uranium than ground sources, but it is highly dilute, which makes harvesting difficult and expensive. In this new effort, the team working in China has found a way to do it much more efficiently, resulting in lower costs. Notably, China builds more nuclear power plants than any other country and would very much like to be able to produce its own uranium.

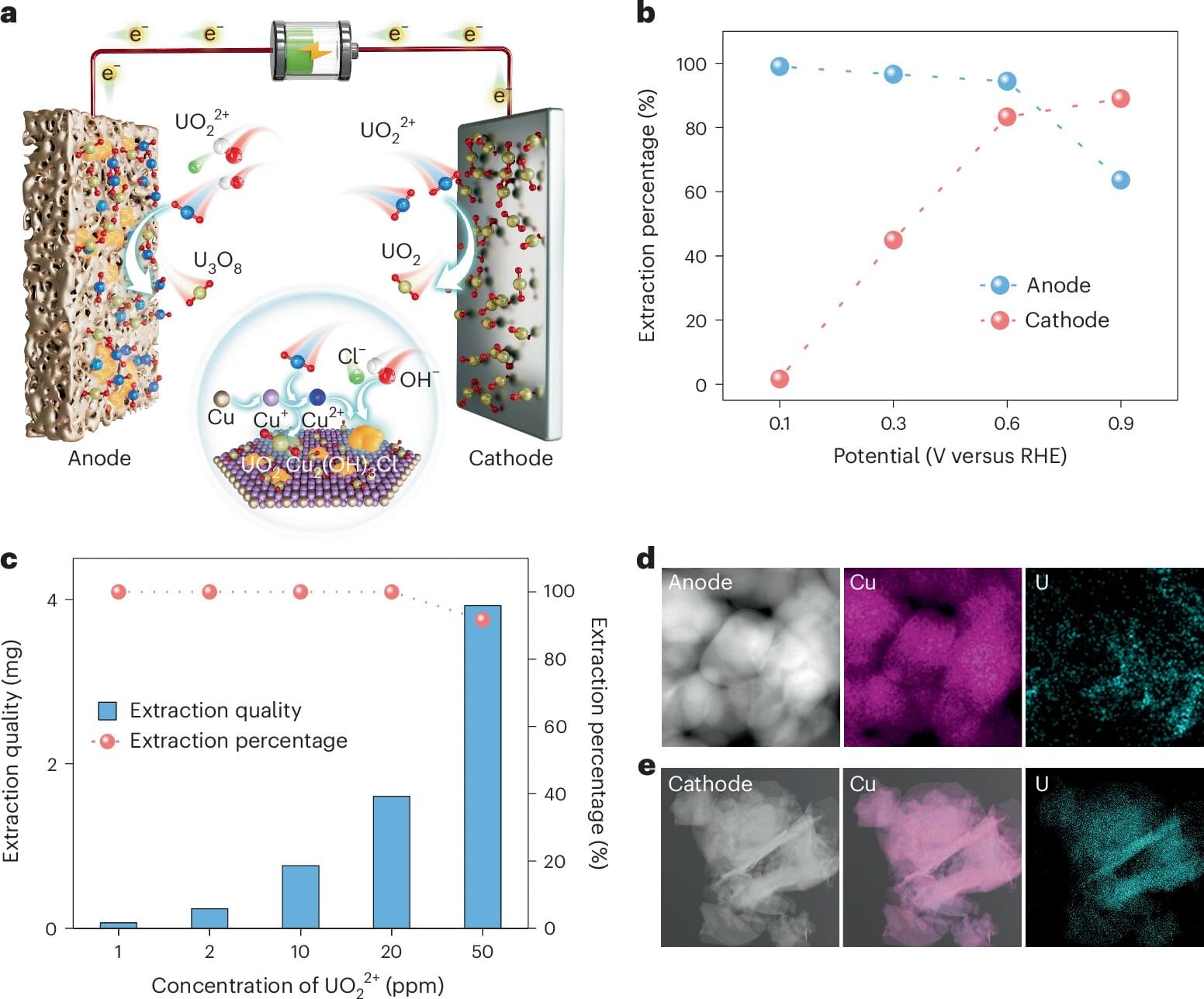

The present century has witnessed a proactive shift toward more sustainable forms of energy, including renewable resources such as solar power, wind, nuclear energy, and geothermal energy. These technologies naturally require robust energy storage systems for future usage. In recent years, lithium-ion batteries have emerged as dominant energy storage systems. However, they are known to suffer from critical safety issues.

In this regard, zinc-ion batteries based on water-based electrolytes offer a promising solution. They are inherently safe, environmentally friendly, as well as economically viable. These batteries also mitigate fire risks and thermal runaway issues associated with their lithium-based counterparts, which makes them lucrative for grid-scale energy storage.

Furthermore, zinc has high capacity, low cost, ample abundance, and low toxicity. Unfortunately, current collectors utilized in zinc-ion batteries, such as graphite foil, are difficult to scale up and suffer from relatively poor mechanical properties, limiting their industrial use.

Arianna Gleason is an award-winning scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory who studies matter in its most extreme forms—from roiling magma in the center of our planet to the conditions inside the heart of distant stars. During Fusion Energy Week, Gleason discussed the current state of fusion energy research and how SLAC is helping push the field forward.

Fusion is at the heart of every star. The tremendous pressure and temperature at the center of a star fuses atoms together, creating many of the elements you see on the periodic table and generating an immense amount of energy.

Fusion is exciting, because it could provide unlimited energy to our power grid. We’re trying to replicate fusion energy here on Earth, though it’s a tremendous challenge for science and engineering.

In collisions of argon and scandium atomic nuclei, scientists from the international NA61/SHINE experiment have observed a clear anomaly indicative of a violation of one of the most important symmetries of the quark world: the approximate flavor symmetry between up and down quarks.

The existence of the anomaly may be due to hitherto unknown inadequacies in current nuclear collision models, but the potential connection to the long-sought-after “new physics” cannot be ruled out.

If we were to assemble a structure using the same number of wooden and plastic blocks, we would expect the proportions between the blocks of the two types not to alter after it has been dismantled. Physicists have so far lived in the belief that a similar symmetry of the initial and final states, called flavor symmetry, occurs in collisions between particles containing up and down quarks.

Among the most enduring designs for a fusion reactor is the tokamak, which uses a doughnut-shaped magnetic field to trap burning plasma. But some of the plasma still interacts with the reactor wall, which can cause severe damage. Now, on one of the key European tokamak experiments, Kenneth Lee of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) and his collaborators have demonstrated a new and potentially efficient way to shed excess heat [1].

The experiment was conducted at the Variable Configuration Tokamak (TCV) on the EPFL campus. Like other modern tokamaks, TCV hosts a so-called X-point: The cross-section of the doughnut’s outer magnetic field features a point at the bottom where the field lines cross, creating an opening for reaction by-products to drain away through a narrow magnetic funnel called a divertor. In 2015, researchers at a tokamak in Germany discovered that plasma at the X-point radiates strongly, thereby removing potentially troublesome thermal energy.

The EPFL team realized they could boost the useful, heat-removing radiation by reconfiguring the confinement field to include a second X-point along the divertor funnel. Experiments at the TCV vindicated this concept, which they call the X-point target radiator (XPTR). What’s more, conditions for filling the XPTR with plasma turned out to be easy to achieve and control. Lee points out that the XPTR concept could be implemented at SPARC, a next-generation tokamak reactor being developed by Commonwealth Fusion Systems, Massachusetts, in collaboration with MIT.

In an unassuming industrial park 30 miles outside Boston, engineers are building a futuristic machine to replicate the energy of the stars. If all goes to plan, it could be the key to producing virtually unlimited, clean electricity in the United States in about a decade.

The donut-shaped machine Commonwealth Fusion Systems is assembling to generate this energy is simultaneously the hottest and coldest place in the entire solar system, according to the scientists who are building it.

It is inside that extreme environment in the so-called tokamak that they smash atoms together in 100-million-degree plasma. The nuclear fusion reaction is surrounded by a magnetic field more than 400,000 times more powerful than the Earth’s and chilled with cryogenic gases close to absolute zero.