When the makers of electronic implants abandon their projects, people who rely on the devices have everything to lose.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a neurological disorder that causes progressive loss of movement, coordination and cognitive function. It is caused by a mutation in a single gene called huntingtin (HTT). More than 200,000 people worldwide live with the genetic condition, approximately 30,000 in the United States. More than a quarter of a million Americans are at risk of inheriting HD from an affected parent. There is no cure.

But in a new study, published December 12, 2022 in Nature Neuroscience, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues elsewhere, describe using RNA-targeting CRISPR/Cas13D technology to develop a new therapeutic strategy that specifically eliminates toxic RNA that causes HD.

CRISPR is known as a genome-editing tool that allows scientists to add, remove or alter genetic material at specific locations in the genome. It is based on a naturally occurring immune defense system used by bacteria. However, current strategies run the risk of off-target edits at unintended sites that may cause permanent and inheritable chromosomal insertions or genome alterations. Because of this, significant efforts have focused on identifying CRISPR systems that target RNA directly without altering the genome.

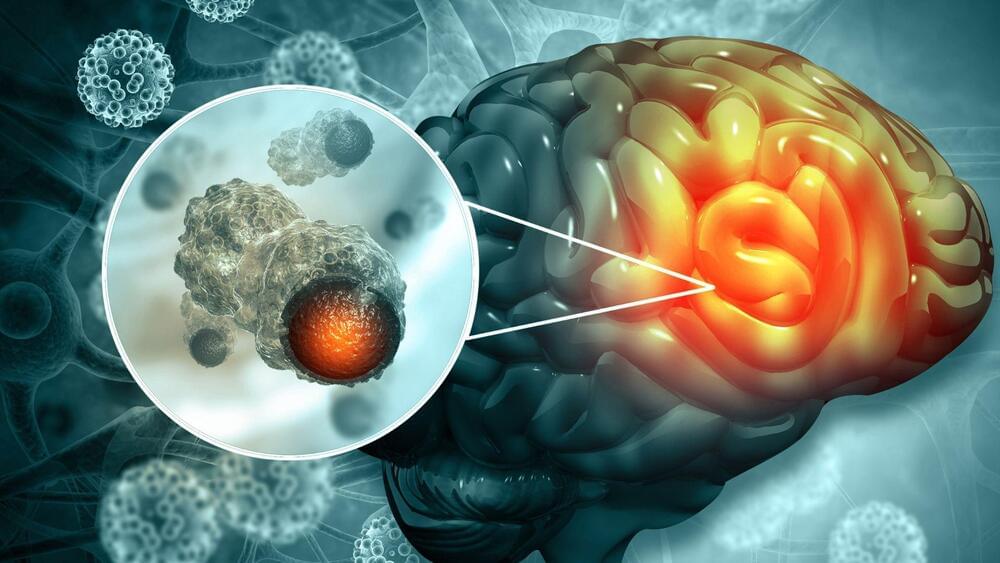

𝐂𝐀𝐑-𝐓-𝐜𝐞𝐥𝐥 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐩𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐥𝐲𝐦𝐩𝐡𝐨𝐦𝐚 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐥

𝘼 𝘾𝘼𝙍-𝙏-𝙘𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙥𝙮 𝙠𝙣𝙤𝙬𝙣 𝙖𝙨 𝙖𝙭𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙗𝙩𝙖𝙜𝙚𝙣𝙚 𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙤𝙡𝙚𝙪𝙘𝙚𝙡 (𝙖𝙭𝙞-𝙘𝙚𝙡) 𝙞𝙨 𝙨𝙖𝙛𝙚 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙨𝙝𝙤𝙬𝙨 𝙚𝙣𝙘𝙤𝙪𝙧𝙖𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙨𝙞𝙜𝙣𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙚𝙛𝙛𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙘𝙮 𝙞𝙣 𝙖 𝙨𝙢𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙥𝙞𝙡𝙤𝙩 𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙖𝙡 𝙞𝙣𝙫𝙤𝙡𝙫𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙥𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙨 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙡𝙮𝙢𝙥𝙝𝙤𝙢𝙖 𝙤𝙛 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙗𝙧𝙖𝙞𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙙/𝙤𝙧 𝙨𝙥𝙞𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙘𝙤𝙧𝙙, 𝘿𝙖𝙣𝙖-𝙁𝙖𝙧𝙗𝙚𝙧 𝘾𝙖𝙣𝙘𝙚𝙧 𝙄𝙣𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙩𝙪𝙩𝙚 𝙞𝙣𝙫𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙜𝙖𝙩𝙤𝙧𝙨 𝙧𝙚𝙥𝙤𝙧𝙩 𝙖𝙩 𝙩𝙝𝙚 64𝙩𝙝 𝘼𝙢𝙚𝙧𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙣 𝙎𝙤𝙘𝙞𝙚𝙩𝙮 𝙤𝙛 𝙃𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙩𝙤𝙡𝙤𝙜𝙮 (𝘼𝙎𝙃) 𝘼𝙣𝙣𝙪𝙖𝙡 𝙈𝙚𝙚𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜.

A CAR-T-cell therapy known as axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) is safe and shows encouraging signs of efficacy in a small pilot trial involving patients with lymphoma of the brain and/or spinal cord, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute investigators report at the 64th American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting.

The research features an in-depth, molecular study of individual CAR-T cells isolated from patients’ blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which surrounds the brain and spinal cord. This unprecedented analysis, conducted in collaboration with the Cellular Therapeutics and Systems Immunology Lab (CTSI), directed by Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, at Dana-Farber and Boston Children’s Hospital, reveals a surprising difference between the two CAR-T-cell populations: the cells in the CSF display a molecular signature that indicates activation of the interferon pathway, an important step in rallying the immune system. These studies are reported in two oral abstracts at ASH. “For many patients with lymphoma of the central nervous system, there aren’t great treatment options,” said Dana-Farber’s Caron Jacobson, MD, MMSc, who led the trial and will present the findings at ASH. “Our early results suggest that expanding the applicability of CAR-T cells to this indication could improve patient outcomes.”

Lymphomas can begin within the brain or spinal cord, or the tumors can spread to those sites (known collectively as the central nervous system or CNS) after they originate in other parts of the body. While the underlying biology of these primary and secondary CNS lymphomas can be quite different, these cancers are often difficult to treat, especially once the tumors evade standard treatments. In that case, patients typically do not live more than 2 years.

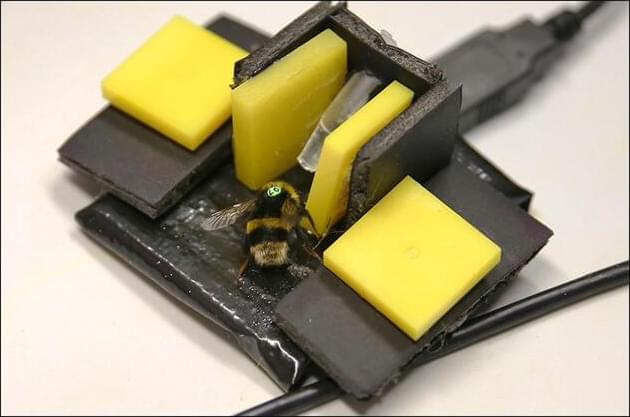

We swat bees to avoid painful stings, but do they feel the pain we inflict? A new study suggests they do, a possible clue that they and other insects have sentience—the ability to be aware of their feelings.

“It’s an impressive piece of work” with important implications, says Jonathan Birch, a philosopher and expert on animal sentience at the London School of Economics who was not involved with the paper. If the study holds up, he says, “the world contains far more sentient beings than we ever realized.”

Previous research has shown honey bees and bumble bees are intelligent, innovative, creatures. They understand the concept of zero, can do simple math, and distinguish among human faces (and probably bee faces, too). They’re usually optimistic when successfully foraging, but can become depressed if momentarily trapped by a predatory spider. Even when a bee escapes a spider, “her demeanor changes; for days after, she’s scared of every flower,” says Lars Chittka, a cognitive scientist at Queen Mary University of London whose lab carried out that study as well as the new research. “They were experiencing an emotional state.”

A biological mechanism has been identified by researchers at Linköping University in Sweden that increases the strength with which fear memories are stored in the brain The research, conducted in rats, was published in the scientific journal Molecular Psychiatry. It provides new insights into the processes behind anxiety-related disorders and identified shared mechanisms of anxiety and alcohol dependence.

The ability to feel fear is critical for escaping life-threatening circumstances and learning how to avoid them in the future. However, in certain conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder that develops in some people who have experienced or witnessed a shocking, scary, or dangerous event.

The study brings much hope to patients with brain and spinal cord cancers.

A small pilot trial involving patients with lymphoma of the brain and/or spinal cord has shown that CAR-T-cell therapy known as axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) can be a viable treatment option for patients who often have little hope, according to a press release by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute investigators published on Sunday. “For many patients with lymphoma of the central nervous system, there aren’t great treatment options,” said Dana-Farber’s Caron Jacobson, MD, MMSc, who led the trial.

Our early results suggest that expanding the applicability of CAR-T cells to this indication could improve patient outcomes.

Mohammed Haneefa Nizamudeen/iStock.

Lymphomas typically feature aggressive tumors that can spread to the brain and spinal cord after they originate in other parts of the body. These cancers are often difficult to treat and patients do not survive more than two years.

An analysis of 22 large-scale gene expression datasets pointed to exercise and activity in general as the most effective theoretical treatment for reversing gene expressions typical of Alzheimer’s disease. Fluoxetine, a well-known antidepressant, also showed effect, particularly when combined with exercise. Curcumin showed positive effects as well. The study was published in Scientific Reports.

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex neurodegenerative disorder that affects multiple brain regions. It is the most common disease that causes dementia and is very difficult to treat. In the course of the disease, abnormal collections of proteins called tau accumulate inside neurons.

Another type of protein clumps together to form so-called amyloid plaques that collect between neurons and disrupt cell functions. These and other changes harm the functioning of the brain across different regions and lead to dysfunction and death of brain cells.

A pleasingly disorienting foray into the fundamental perplexity of life.