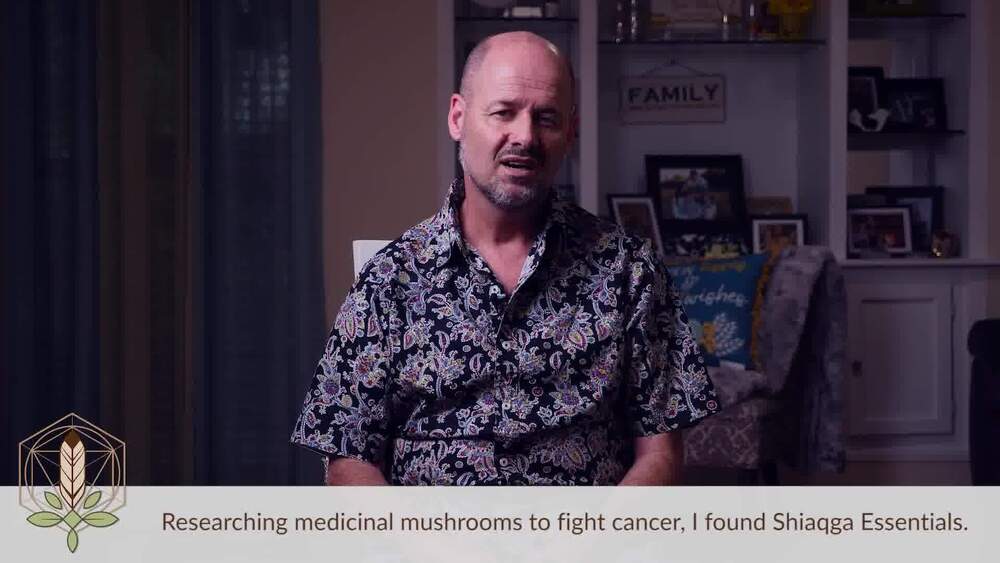

By mushrooms…?

People like Nathan have found out first hand that they can. You may have also seen scientists and doctors talking about mycotherapy for serious chronic conditions like cancer and HIV. That’s because many conditions thought of as diseases really have the same cause– an immune system that was unbalanced and compromised by environmental factors or diet.

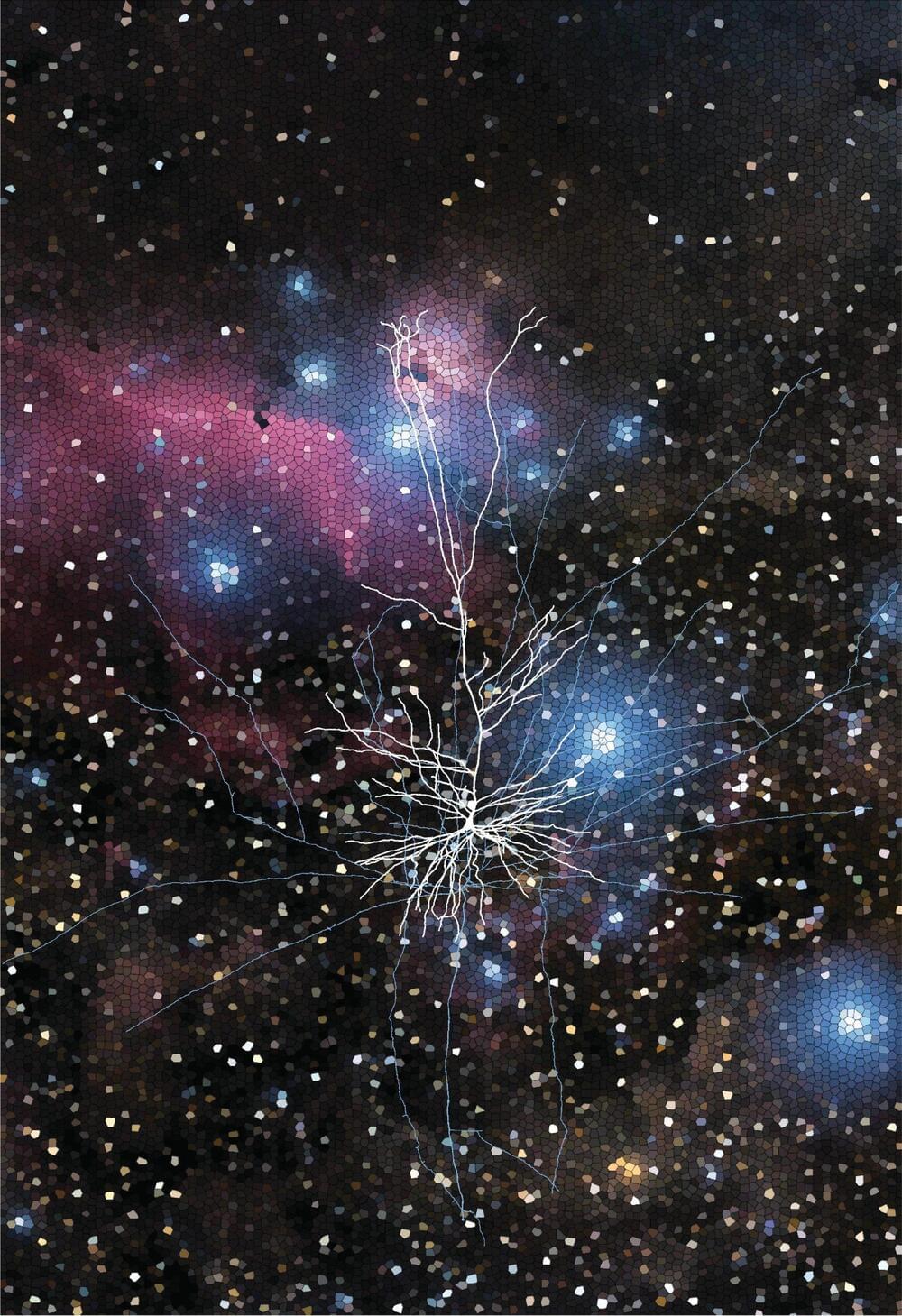

Certain foods we eat are inflammatory, they boost problematic cells in our body called TH2 cytokines, which cause inflammation, and these cells can cause allergic reactions, auto-immune conditions, and weaken the cancer-fighting TH1 cytokines. When the TH1 cytokines are weakened by inflammatory foods, cancer is allowed to thrive and grow and spread.

But our bodies naturally have the ability to fight diseases and cancers, that’s what our immune system’ does.

The cells responsible for finding and removing cancer in our body, the TH1 cytokines, do this amazingly– but inflammatory foods and environments shut them down and prevent these natural cells from doing their jobs and killing cancerous cells quickly.

The best way to help reverse this process is by eliminating inflammatory foods and using nature’s miracle– mushrooms.

Many mushrooms are immune stimulating and modulating. Mushrooms like the Shiaqga mushroom with a high concentration of beta-glucans help boost the immune systems and support effective T-cell activity.