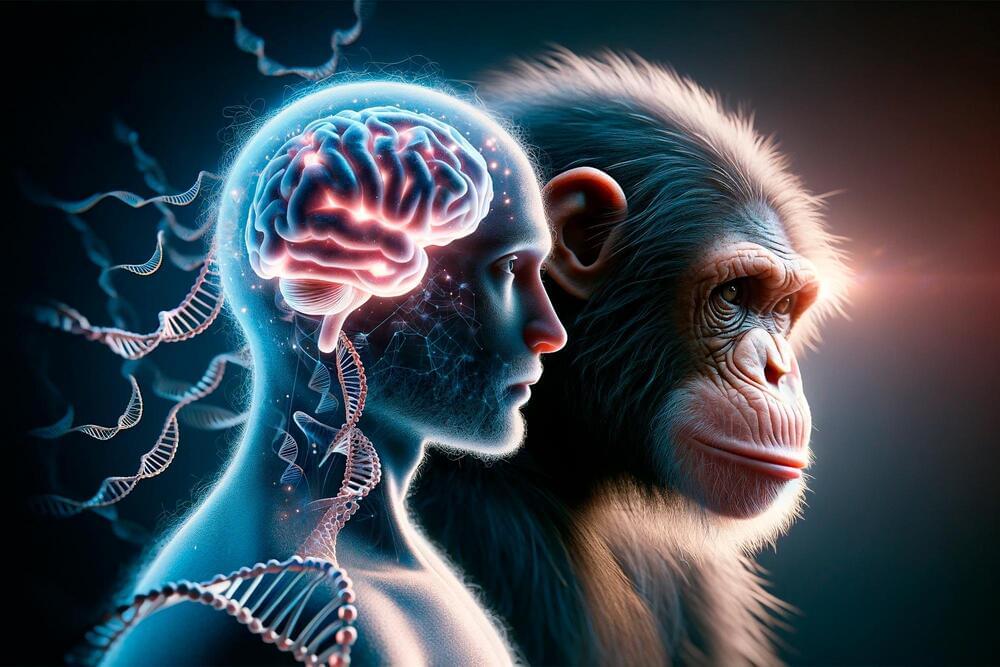

Primates are among the most intelligent creatures with distinct cognitive abilities. Their brains are relatively large in relation to their body stature and have a complex structure. However, how the brain has developed over the course of evolution and which genes are responsible for the high cognitive abilities is still largely unclear. The better our understanding of the role of genes in brain development, the more likely it will be that we will be able to develop treatments for serious brain diseases.

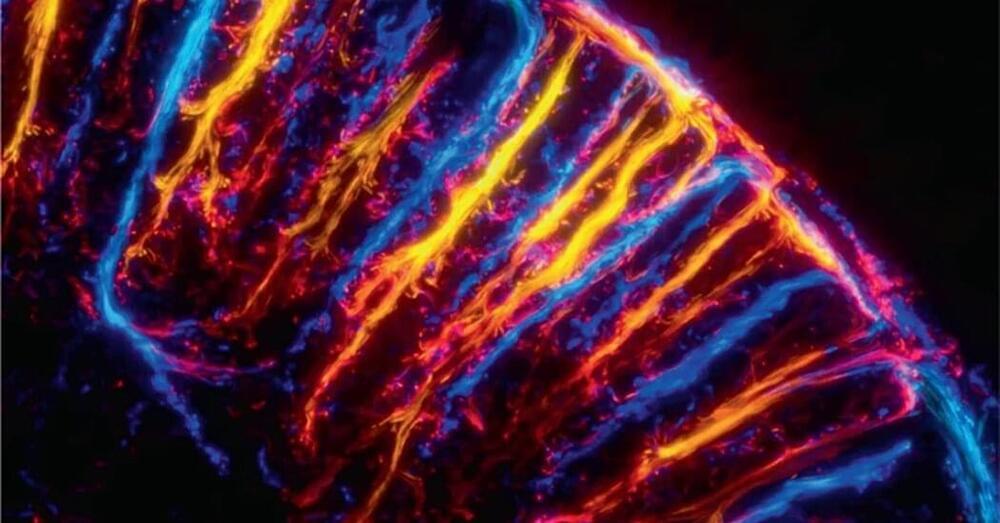

Researchers are approaching these questions by knocking out or activating individual genes and thus drawing conclusions about their role in brain development. To avoid animal experiments as far as possible, brain organoids are used as an alternative. These three-dimensional cell structures, which are only a few millimeters in size, reflect different stages of brain development and can be genetically modified. However, such modifications are usually very complex, lengthy and costly.

Researchers at the German Primate Center (DPZ)—Leibniz Institute for Primate Research in Göttingen have now succeeded in genetically manipulating brain organoids quickly and effectively. The procedure requires only a few days instead of the usual several months and can be used for organoids of different primate species. The brain organoids thus enable comparative studies of the function of genes at early stages of brain development in primates and help to better understand neurological diseases.