UCLA Department of Integrative Biology and PhysiologyLuskin Endowment forLeadership SymposiumPushing the Boundaries: Neuroscience, Cognition, and LifeKarl Fris…

Category: neuroscience – Page 510

Brain Inflammation May Underlie Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia

I’m thinking my autistic sister has this. Maybe my 80 year old mother too. Short but informative article.

Neuroinflammation—as measured by levels of activated microglia, the brain’s immune cells—was strongly linked with irritability, agitation, and nighttime disturbances in people with dementia, recent research found. The results, published in JAMA Network Open, were based on data from a cross-sectional study that involved 109 participants aged 38 to 87 years, about two-thirds of whom did not have cognitive impairment.

Higher levels of microglial activation, and particularly microglial activation–associated irritability, in participants with dementia were also tied to greater distress in their caregivers, family members, or close friends.

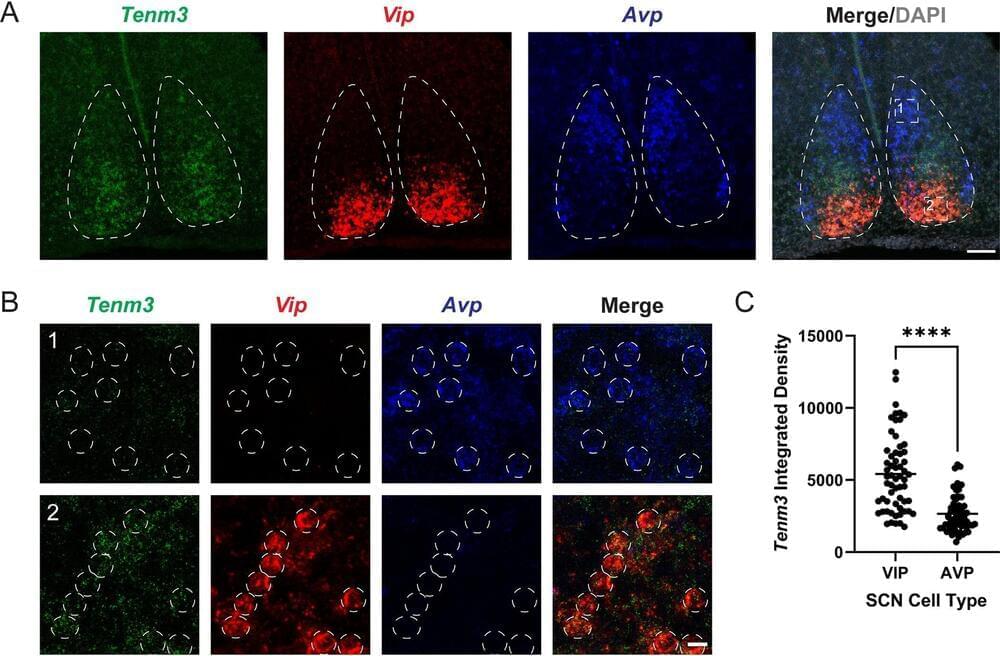

Study identifies ‘visual system’ protein for circadian rhythm stability

Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health have identified a protein in the visual system of mice that appears to be key for stabilizing the body’s circadian rhythms by buffering the brain’s response to light. The finding, published Dec. 5 in PLoS Biology, advances efforts to better treat sleep disorders and jet lag, the study authors say.

“If circadian rhythms adjusted to every rapid change in illumination, say an eclipse or a very dark and rainy day, they would not be very effective in regulating such periodic behaviors as sleep and hunger. The protein we identified helps wire the brain during neural development to allow for stable responses to circadian rhythm challenges from day to day,” says Alex Kolodkin, Ph.D., professor in the Johns Hopkins Department of Neuroscience and deputy director for the Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences.

Kolodkin co-led the study with Samer Hattar, Ph.D., chief of the Section on Light and Circadian Rhythms at the National Institute of Mental Health.

A Journey into Chaos: Creativity and the Unconscious**

The capacity to be creative, to produce new concepts, ideas, inventions, objects or art, is perhaps the most important attribute of the human brain. We know very little, however, about the nature of creativity or its neural basis. Some important questions include how should we define creativity? How is it related (or unrelated) to high intelligence? What psychological processes or environmental circumstance cause creative insights to occur? How is it related to conscious and unconscious processes? What is happening at the neural level during moments of creativity? How is it related to health or illness, and especially mental illness? This paper will review introspective accounts from highly creative individuals. These accounts suggest that unconscious processes play an important role in achieving creative insights. Neuroimaging studies of the brain during “REST” (random episodic silent thought, also referred to as the default state) suggest that the association cortices are the primary areas that are active during this state and that the brain is spontaneously reorganising and acting as a self-organising system. Neuroimaging studies also suggest that highly creative individuals have more intense activity in association cortices when performing tasks that challenge them to “make associations.” Studies of creative individuals also indicate that they have a higher rate of mental illness than a noncreative comparison group, as well as a higher rate of both creativity and mental illness in their first-degree relatives. This raises interesting questions about the relationship between the nature of the unconscious, the unconscious and the predisposition to both creativity and mental illness.

Keywords: Creativity, Complexity, Consciousness, Default mode, Functional imaging, Self-organising systems, The Unconscious, Resting state, REST

Creativity is one of our most valued human traits. It has given human beings the ability to change the world that they live in; and it has also, paradoxically, given them the ability to adapt to changes in the world over which they have no control. Our highly developed capacity to develop and implement new ideas arises from our highly developed human brain. Understanding how creative ideas arise from the brain is one of the most fascinating challenges of contemporary neuroscience.

Protein Discovery Sheds Light on Circadian Rhythms

Summary: Researchers identify a crucial protein, Tenm3, in mice’s visual system that stabilizes circadian rhythms by modulating the brain’s response to light. This discovery has significant implications for treating sleep disorders and jet lag.

Circadian rhythms play a vital role in regulating sleep, alertness, and other cyclic behaviors, and disruptions can lead to health problems.

By understanding Tenm3’s role, researchers aim to develop interventions for sleep disorders and jet lag, ultimately benefiting human health.

Intermittent Fasting Seems to Result in Dynamic Changes to The Human Brain

Scientists looking to tackle our ongoing obesity crisis have made an important discovery: Intermittent fasting leads to significant changes both in the gut and the brain, which may open up new options for maintaining a healthy weight.

Researchers from China studied 25 volunteers classed as obese over a period of 62 days, during which they took part in an intermittent energy restriction (IER) program – a regime that involves careful control of calorie intake and fasting on some days.

Not only did the participants in the study lose weight – 7.6 kilograms (16.8 pounds) or 7.8 percent of their body weight on average – there was also evidence of shifts in the activity of obesity-related regions of the brain, and in the make-up of gut bacteria.

From Language to Consciousness (Guest: Joscha Bach)

Guest lecture by Joscha Bach on the past and future of language models.

Quantum Physics and the End of Reality | Sabine Hossenfelder, Carlo Rovelli, Eric Weinstein

Last year, I edhost a thrilling conversation between @SabineHossenfelder, Carlo Rovelli, and Eric Weinstein as they debate quantum physics, consciousness and the mystery of reality. \

\

IAI Live is a monthly event featuring debates, talks, interviews, documentaries and music. LIVE. \

Watch the original video \

\

See the world’s leading thinkers debate the big questions for real, LIVE in London. Tickets: https://howthelightgetsin.org/\

\

To discover more talks, debates, interviews and academies with the world’s leading speakers visit https://iai.tv/\

\

We imagine physics is objective. But quantum physics found the act of human observation changes the outcome of experiment. Many scientists assume this central role of the observer is limited to just quantum physics. But is this an error? As Heisenberg puts it, \.