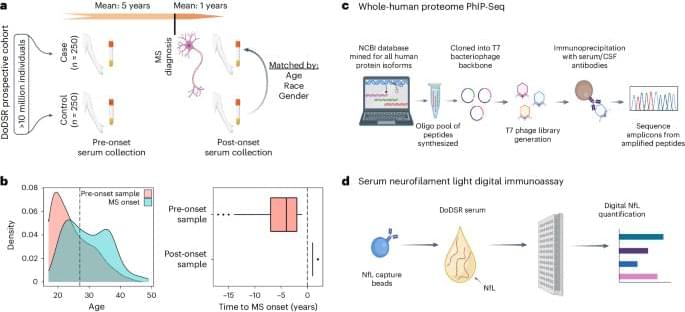

An antibody screen of two distinct multiple sclerosis cohorts reveals an autoantibody signature that is detectable years before symptom onset and linked to a common microbial motif, according to a paper in Nature Medicine. Read the paper:

Abstract. In recent years, brain research has indisputably entered a new epoch, driven by substantial methodological advances and digitally enabled data integration and modelling at multiple scales—from molecules to the whole brain. Major advances are emerging at the intersection of neuroscience with technology and computing. This new science of the brain combines high-quality research, data integration across multiple scales, a new culture of multidisciplinary large-scale collaboration, and translation into applications. As pioneered in Europe’s Human Brain Project (HBP), a systematic approach will be essential for meeting the coming decade’s pressing medical and technological challenges.

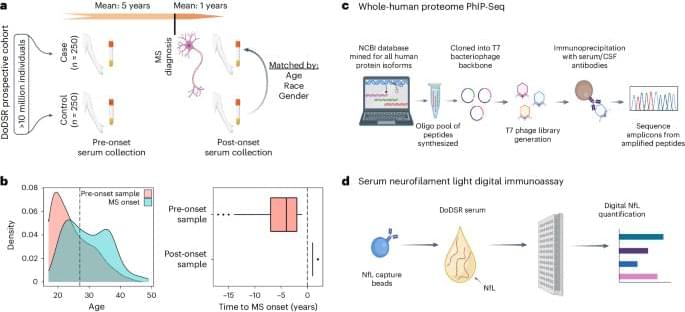

Single-cell multiplexing techniques (cell hashing and genetic multiplexing) combine multiple samples, optimizing sample processing and reducing costs. Cell hashing conjugates antibody-tags or chemical-oligonucleotides to cell membranes, while genetic multiplexing allows to mix genetically diverse samples and relies on aggregation of RNA reads at known genomic coordinates. We develop hadge (hashing deconvolution combined with genotype information), a Nextflow pipeline that combines 12 methods to perform both hashing-and genotype-based deconvolution. We propose a joint deconvolution strategy combining best-performing methods and demonstrate how this approach leads to the recovery of previously discarded cells in a nuclei hashing of fresh-frozen brain tissue.

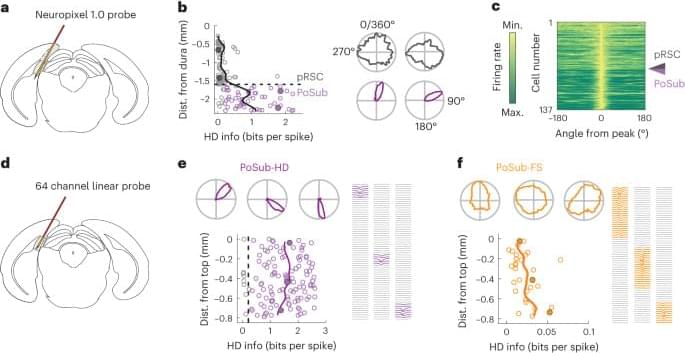

Varying the parameters of weight distribution did not account for the observed amount of HD information conveyed by PoSub-FS cells (Fig. 2a). Rather, we found that the number of inputs received by each output unit was a key factor influencing the amount of HD information (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Varying both weight distribution and the number of input units, we obtained a distribution of HD information in output tuning curves that matched the real data (Extended Data Fig. 5f), revealing that the tuning of PoSub-FS cells can be used to estimate both the distribution of weights and the number of input neurons. Notably, under optimal network conditions, Isomap projection of output tuning curve auto-correlograms has a similar geometry to that of real PoSub-FS cells (Extended Data Fig. 5g), confirming similar distribution of tuning shapes.

To further quantify the relative contributions of ADN and local PoSub inputs to PoSub-FS cell tuning, we expanded the simulation to include the following two inputs: one with tuning curve widths corresponding to ADN-HD cells and one with tuning curve widths corresponding to PoSub-HD cells (Fig. 4h, left). We then trained the model using gradient descent to find the variances and means of input weights that result in the best fit between the simulated output and real data. The combination of parameters that best described the real data resulted in ADN inputs distributed in a near Gaussian-like manner but a heavy-tailed distribution of PoSub-HD inputs (Fig. 4h, middle). Using these distribution parameters, we performed simulations to determine the contribution of ADN-HD and PoSub-HD inputs to the output tuning curves and established that PoSub-FS cell-like outputs are best explained by flat, high firing rate inputs from ADN-HD cells and low firing rate, HD-modulated inputs from PoSub-HD cells (Fig. 4h, right).

Our simulations, complemented by direct analytical derivation (detailed in the Supplementary Methods), not only support the hypothesis that the symmetries observed in PoSub-FS cell tuning curves originate from local cortical circuits but also demonstrate that these symmetries emerge from strongly skewed distributions of synaptic weights.

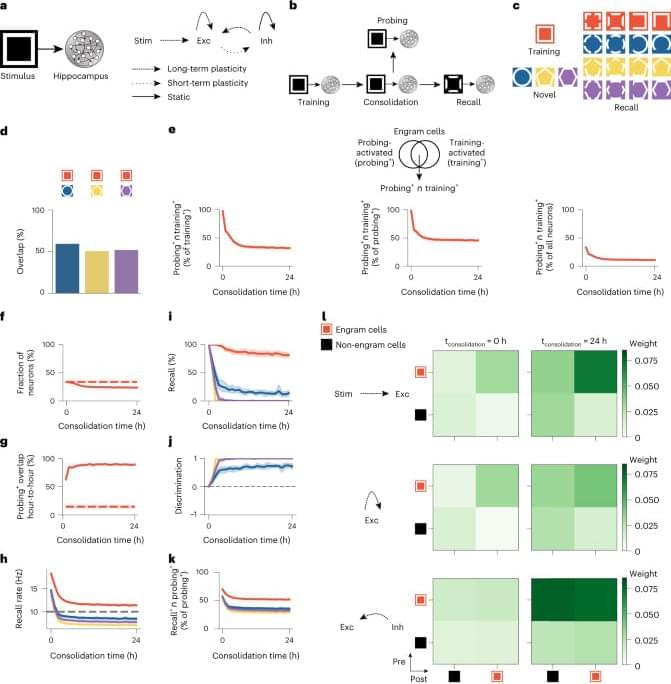

The changes in engram composition and selectivity observed in our model were associated with ongoing synaptic plasticity during memory consolidation (Fig. 1l). Feedforward synapses from training stimulus neurons (that is, sensory engram cells; Methods) onto hippocampal engram cells were strengthened over the course of memory consolidation, and, consequently, the synaptic coupling between the stimulus population and the hippocampus network was increased. Recurrent excitatory synapses between engram cells also experienced a modest gain in synaptic efficacy. Notably, inhibitory synapses from inhibitory engram cells onto both engram and non-engram cells were strongly potentiated throughout memory consolidation. This indicated that a number of training-activated engram cells were forced out of the engram due to strong inhibition, and, consequently, only neurons highly responsive to the training stimulus remained in the engram, in line with our previous analysis (Fig. 1e). Inhibitory neurons also controlled the overall activity of excitatory neurons in the network through inhibitory synaptic plasticity (Extended Data Fig. 2h).

To investigate the contribution of synaptic plasticity to the engram dynamics in our model, we performed several manipulations in our simulations. First, we blocked the reactivation of the training stimulus during memory consolidation and found that this altered the temporal profile of engrams and prevented them from becoming selective (Extended Data Fig. 3a–i). These effects were associated with reduced potentiation of inhibitory synapses onto engram cells (compare Extended Data Fig. 3i to Fig. 1l, bottom rows). Previous experiments demonstrated that sleep-specific inhibition of learning-activated sensory neurons disrupts memory selectivity11, and, hence, our model was consistent with these findings, and it predicted underlying mechanisms. Second, blocking long-term potentiation (LTP) during memory consolidation almost completely eliminated engram cell turnover after a steady state was reached, and it also impaired memory recall relative to the control case (Extended Data Fig. 4a–i). Reduced feedforward and recurrent excitatory synaptic weights due to LTP blockage led to engram stabilization and impaired recall (compare Extended Data Fig. 4h to Fig. 1l, top and middle rows). These results are in line with a recent study showing that memory recall is impaired when LTP is optically erased selectively during sleep14. Third, we separately blocked the Hebbian and non-Hebbian forms of long-term excitatory synaptic plasticity in our model and verified that each was essential for memory encoding and consolidation (Extended Data Fig. 5). These results are consistent with a previously reported mean-field analysis showing that this combination of plasticity mechanisms can support stable memory formation and recall9. Fourth, we blocked inhibitory synaptic plasticity in our entire simulation protocol, and this disrupted the emergence of memory selectivity in our network model (Extended Data Fig. 6a–h). This demonstrated that excitatory synaptic plasticity alone could not drive an increase in memory selectivity because it could not increase competition among excitatory neurons in the absence of inhibitory synaptic plasticity (compare Extended Data Fig. 6h to Fig. 1l). However, excitatory synaptic plasticity could promote engram cell turnover on its own in an even more pronounced manner than in the presence of both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic plasticity (compare Extended Data Fig. 6b to Fig. 1g). Finally, we found that an alternative inhibitory synaptic plasticity formulation yielded engram dynamics analogous to those in our original network (compare Extended Data Fig. 7a–h to Fig. 1e–l). This suggested that the dynamic and selective engrams predicted by our model are not a product of a specific form of inhibitory plasticity but a consequence of memory encoding and consolidation in inhibition-stabilized plastic networks in general.

We also conduced loss-of-function and gain-of-function manipulations to examine the role of training-activated engram cells in memory recall in our model (Fig. 2). We found that blocking training-activated engram cells after a consolidation period of 24 h prevented memory recall (Fig. 2a), whereas artificially reactivating them in the absence of retrieval cues was able to elicit recall (Fig. 2b), in a manner consistent with previous experimental findings3,4 and despite the dynamic nature of engrams in our simulations (Fig. 1e–g). Thus, our model was able to reconcile the prominent role of training-activated engram cells in memory storage and retrieval with dynamic memory engrams. To determine whether neuronal activity during memory acquisition was predictive of neurons dropping out of or dropping into the engram, we examined the distribution of stimulus-evoked neuronal firing rates in the training phase (Extended Data Fig. 3j–m). We found that training-activated engram cells that remained part of the engram throughout memory consolidation exhibited higher stimulus-evoked firing rates than the remaining neurons in the network (Extended Data Fig. 3j) and training-activated engram cells that dropped out of the engram over the course of consolidation (Extended Data Fig. 3k). Therefore, stimulus-evoked firing rates during training were indicative of a neuron’s ability to outlast inhibition and remain part of the engram after initial memory encoding. We also verified that neurons that were not engram cells at the end of training but later dropped into the engram displayed lower training stimulus-evoked firing rates than the remaining neurons in the network (Extended Data Fig. 3l). Surprisingly, neurons that dropped into the engram after training showed slightly lower stimulus-evoked firing rates than neurons that failed to become part of the engram altogether (Extended Data Fig. 3m). This suggested that stimulus-evoked firing rates during memory acquisition may not be reliable predictors of a neuron’s ability to increase its response to the training stimulus and become an engram cell after encoding. Lastly, we found that using a neuronal population-based approach to identify engram cells in our simulations yielded analogous engram dynamics (compare Extended Data Fig. 4j–o to Fig. 1e−j and Extended Data Fig. 2i–n to Extended Data Fig. 2b−g; Methods).

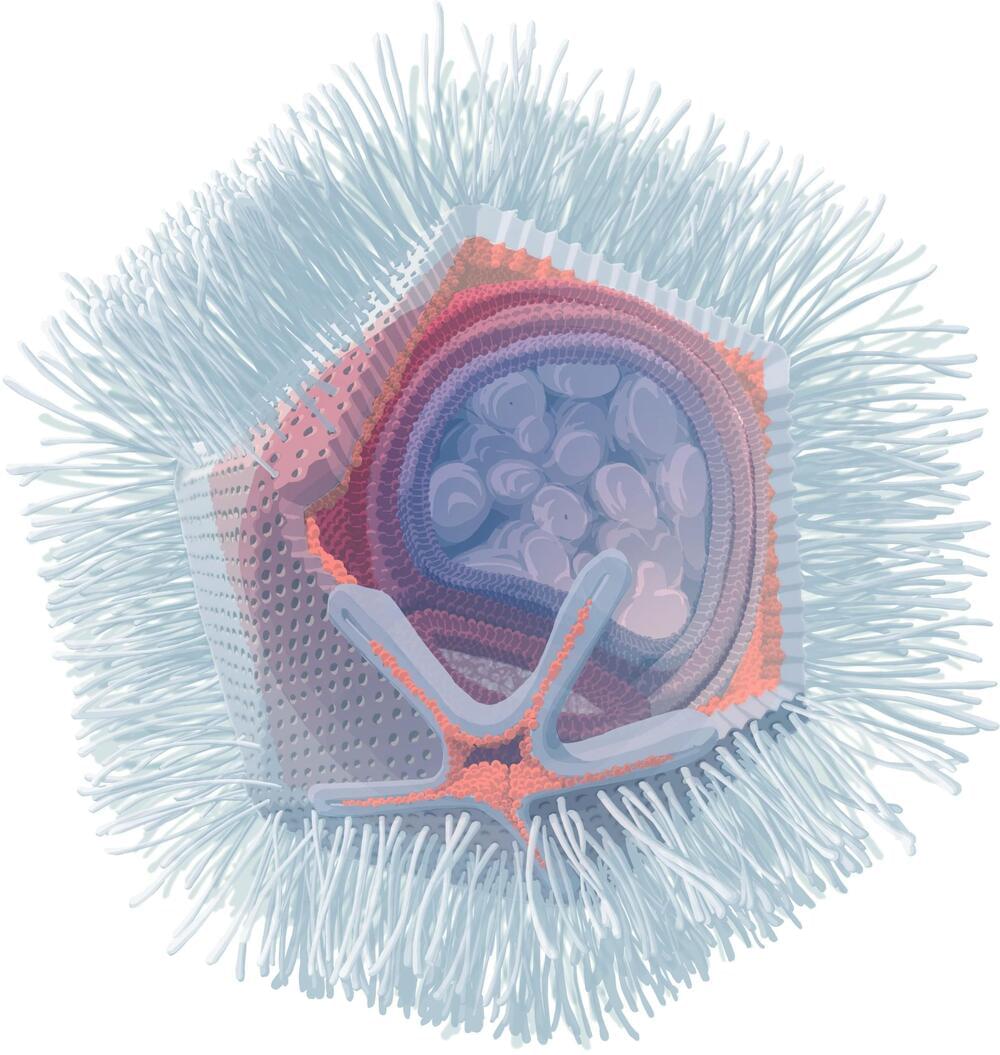

The single-celled organism Naegleria fowleri ranks among the deadliest human parasites. Matthias Horn and Patrick Arthofer of the University of Vienna’s Center for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science, along with other researchers, have identified viruses that target this dangerous organism.

Named Naegleriavirus, these belong to the giant viruses, a group known for their unusually large particles and complex genomes. The team details their findings in the prestigious journal, Nature Communications.

Naegleri species are single-celled amoebae, found globally in water bodies. Notably, one species, Naegleria fowleri, thrives in warm waters above 30°C and causes primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a rare but almost invariably fatal brain infection. A research team led by Patrick Arthofer and Matthias Horn from the University of Vienna’s Center for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science (CeMESS) has now isolated giant viruses that infect various Naegleria species.

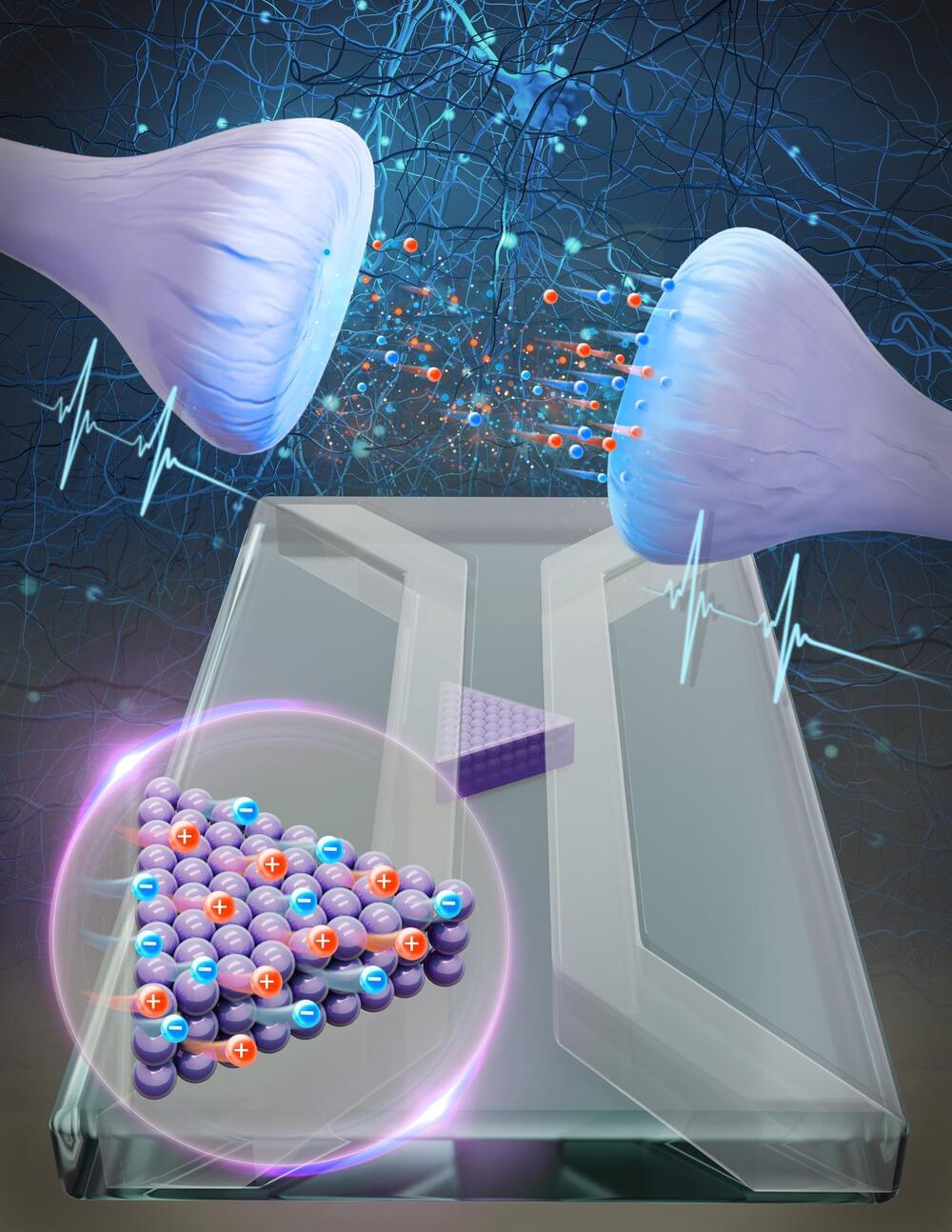

Theoretical physicists at Utrecht University, together with experimental physicists at Sogang University in South Korea, have succeeded in building an artificial synapse. This synapse works with water and salt and provides the first evidence that a system using the same medium as our brains can process complex information.

The results appear in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In the pursuit of enhancing the energy efficiency of conventional computers, scientists have long turned to the human brain for inspiration. They aim to emulate its extraordinary capacity in various ways.