Sepsis is a condition in which the body responds improperly. More specifically, the infection causes the organs in the body to shut down. This is a serious illness which could lead to extremely low blood pressure or septic shock. In this case, permanent damage to the lungs, kidneys, liver, and other organs can occur. Unfortunately, if the damage is extensive enough, it could be fatal. Common symptoms associated with sepsis includes alteration of mental status, shallow breathing, sweating out of context, lightheadedness, chills, and other symptoms associated with infection or fever. Sepsis can lead to septic shock and raises the risk of death. Symptoms of septic shock include inability to stand, sleepiness, and extreme confusion. Interestingly, symptoms can vary between people, and it is important to monitor bodily changes to detect sepsis as early as possible. Bacterial, viral, or fungal infections can lead to sepsis including common infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and burns, among others. It is critical to see a doctor if you suspect you are not getting better or if your symptoms worsen. Early detection of sepsis can help improve survival rate and prevent permanent organ damage. Treatments include antibiotics, increased fluids, vasopressors to increase blood pressure, and steroids. Although scientists and physicians have worked to understand sepsis and how to treat it, other discoveries are yet to be made.

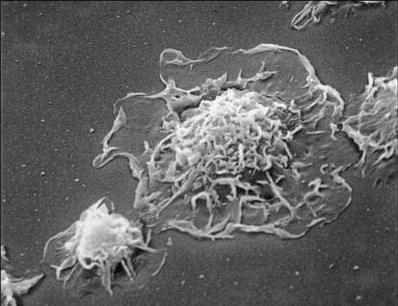

A recent study in Nature Immunology by Dr. Antoine Roquilly from Nantes University in France, demonstrated that patients that experienced sepsis build strong immune cells that aid in the prevention of tumor development. It was previously unknown how the immune landscape was shaped after a patient recovered from sepsis. Roquilly and his team wanted to understand the relationship between these exposed immune cells and the risk of developing cancer in the future.

Roquilly’s research team first analyzed big datasets that consisted of information from patients who survived sepsis. Researchers were able to determine the risk of cancer prevalence up to 10 years following the discharge from the hospital for sepsis patients. Interestingly, sepsis survivors had lower risk of developing cancer compared to those that did not have sepsis.