At Stanford, a treatment that aims magnetic pulses at the brain is showing results for people with treatment-resistant depression. It’s called SAINT, and here’s how it works.

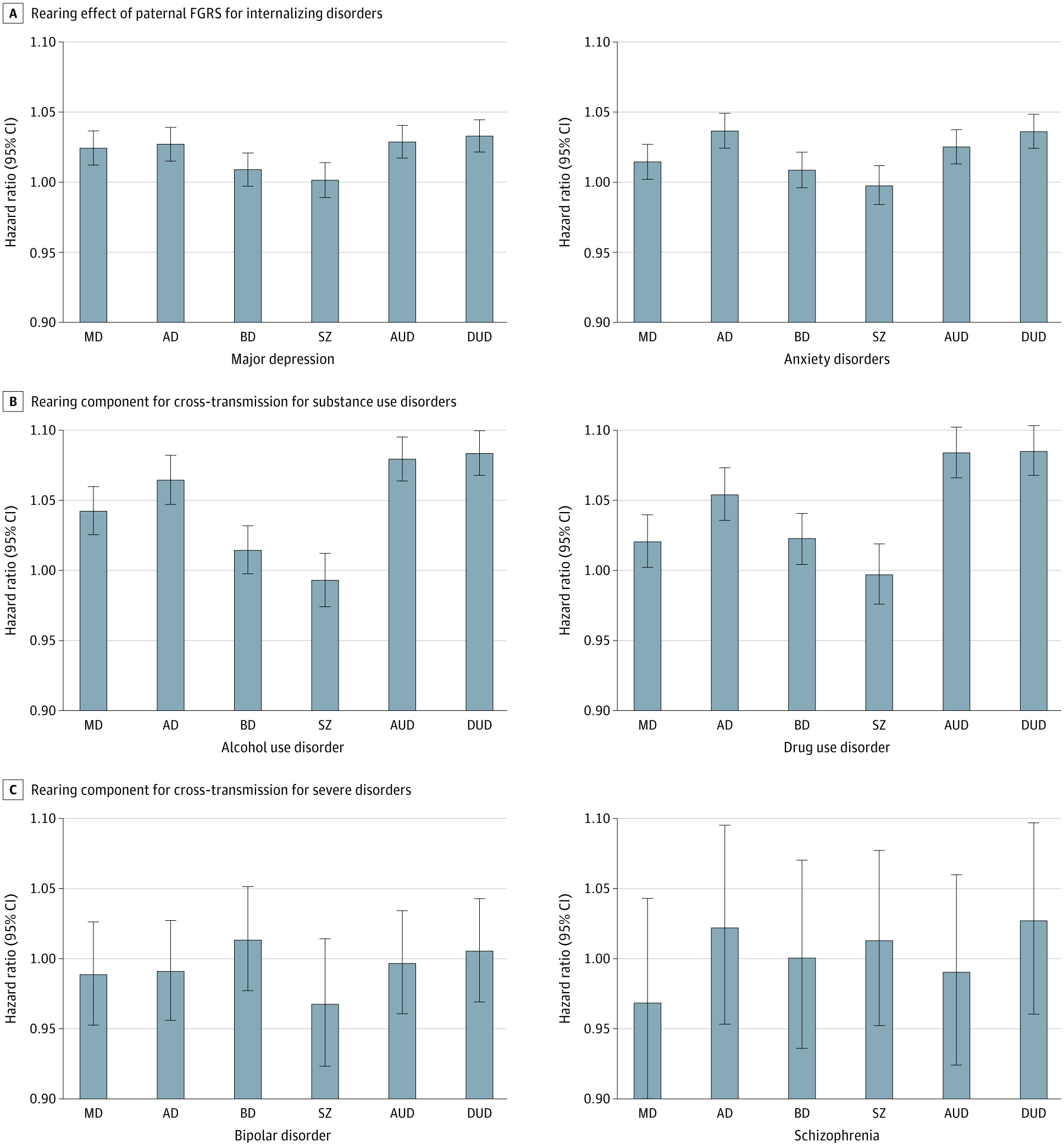

Paternal genetic risk is a robust predictor of offspring psychiatric disorders, with additional “indirect genetic effects” observed for internalizing and substance use conditions in adoptive and stepfather relationships. Rearing effects were most pronounced for substance use disorders.

Question In an adoption study of major psychiatric illness, what results would be obtained if offspring risk were predicted not from the phenotype of the parents but from their genetic risk?

Findings In this cohort study, paternal genetic risk was associated with offspring risk of illness for all disorders in genetically related father-offspring pairs. In an indirect pathway, genetic risk in adoptive and stepfathers predicted risk in their offspring for internalizing and substance use disorders but not for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Meaning Indirect genetic effects from the father may have an impact on offspring risk of internalizing and substance use disorders.

Researchers at the Children’s Cancer Institute and UNSW Sydney have tested a new way of treating childhood brain cancer by combining two medicines in lab studies. They found using the two treatments together may work better than using either on its own. The research is published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

In the new study, Children’s Cancer Institute and UNSW Sydney researchers lab-tested a combined therapy approach on a group of difficult-to-treat brain tumors: diffuse midline gliomas (DMG). This group includes diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a rare but fatal childhood brain cancer. Children diagnosed with DIPG usually survive for about 12 months.

UNSW Conjoint Professor David Ziegler and UNSW Conjoint Associate Professor Maria Tsoli led the study. They have been working for many years to find better treatments for DIPG.

A subtle change in brain wave activity could predict Alzheimer’s disease more than two years before diagnosis, according to a new study.

The signal could prove to be a sensitive biomarker of cognitive decline.

Using a noninvasive imaging technique called magnetoencephalography (MEG), neuroscientists at Brown University in the US and Spain’s Complutense University of Madrid and University of La Laguna analyzed the resting brain wave activity of 85 patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment.

Survey: Online ADHD coaching has increased substantially since the pandemic, mostly by lay adults reporting lived experience with ADHD, as a rising alternative to formal ADHD care.

This survey study found that most ADHD coaches primarily operated outside the US health care system and reported workforce entry after the COVID-19 pandemic’s onset. Our findings suggest ADHD coaching is usually delivered through a 1:1 virtual format using a traditional outpatient psychotherapy model (weekly 1-hour sessions) and reached prospective clients through a combination of online marketing and health care referrals. ADHD coaches tended to be individuals without formal mental health training who self-identified as having ADHD (or a loved one with ADHD), may have received ADHD coaching themselves, and based practices on lived experiences. Unlike most licensed mental health clinicians, ADHD coaches practiced across state and international borders.

As expected, we detected a spike in ADHD coaching workforce entry at the COVID-19 pandemic’s outset that mirrored similar ADHD medication prescribing patterns.6 Herein, we reveal that intervention content self-reported by ADHD coaches is similar to those manualized in evidence-based CBTs for ADHD.37 The potential redundancy in content between ADHD coaching and CBT for ADHD could make it difficult for prospective clients and some medical clinicians to differentiate between these approaches. However, the aforementioned aspects of ADHD coaching are different than traditional CBTs in that ADHD coaching appears longer term, involves sharing lived experiences with ADHD, and offers support between sessions (Table 2).38-40 These features may make ADHD coaching especially palatable to adults with ADHD, who reportedly criticize routine care CBT as being too rigid, generic, and short term, with therapists who are stigmatizing, negativistic about ADHD, and unempathetic.

A new study published in Neuropsychopharmacology suggests that the use of oral contraceptives may influence how the brain regulates fear responses in safe environments. The research indicates that women who use birth control pills, particularly those with higher doses of synthetic estrogen, may experience elevated fear in safe contexts compared to women who have never used hormonal contraception. The findings also imply that these alterations in fear processing could persist for a significant period after an individual stops taking the medication.

Anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder are nearly twice as prevalent in women as they are in men. Biological factors likely contribute to this disparity, with sex hormones acting as potential mediators. Specifically, the hormone estradiol plays a significant role in how the brain manages fear and memory.

Effective fear regulation requires the ability to distinguish between a threat and a safety signal based on the surrounding environment. For example, seeing a snake in a forest might require a fear response, while seeing a snake in a zoo enclosure should not. This process is known as contextual fear regulation.