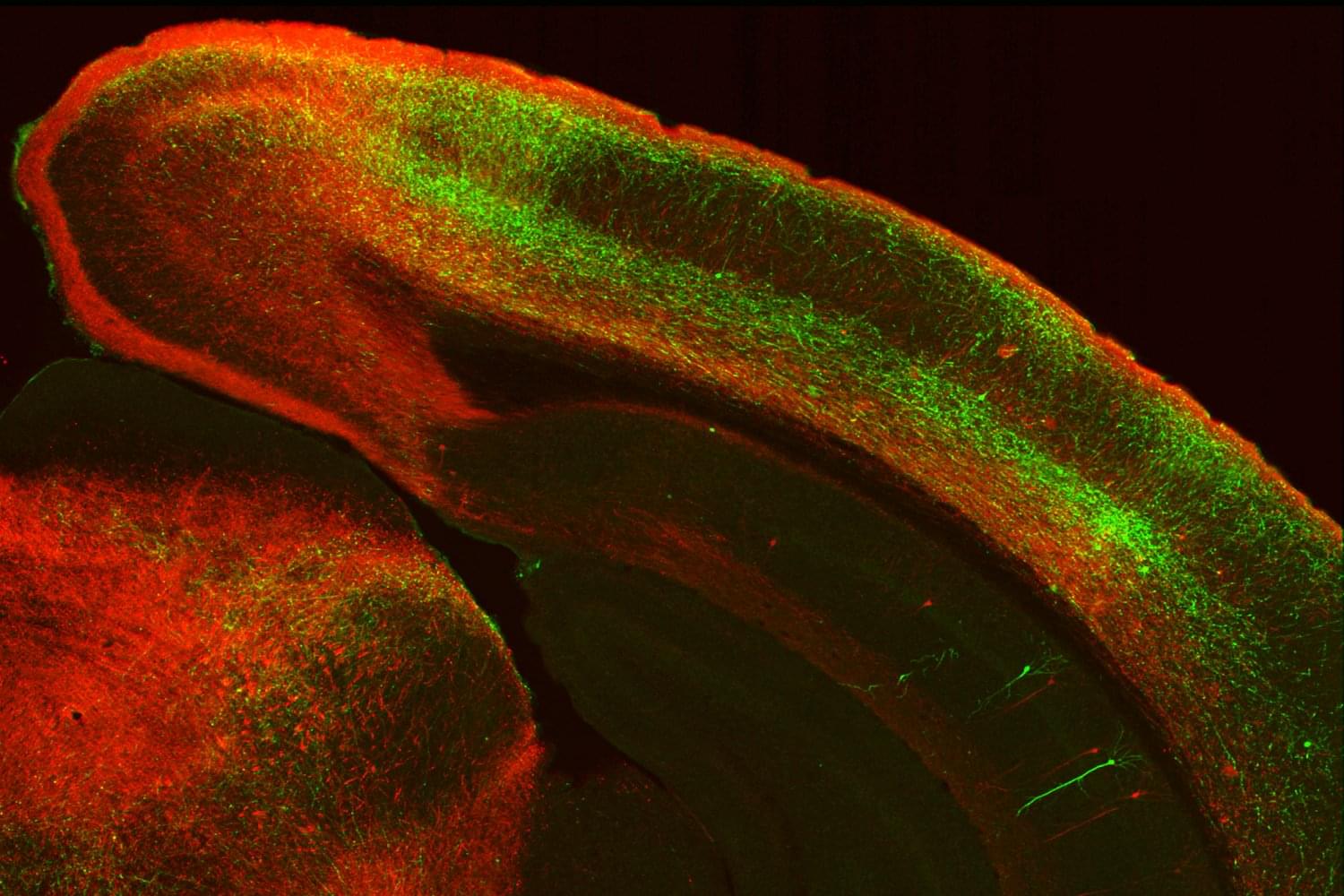

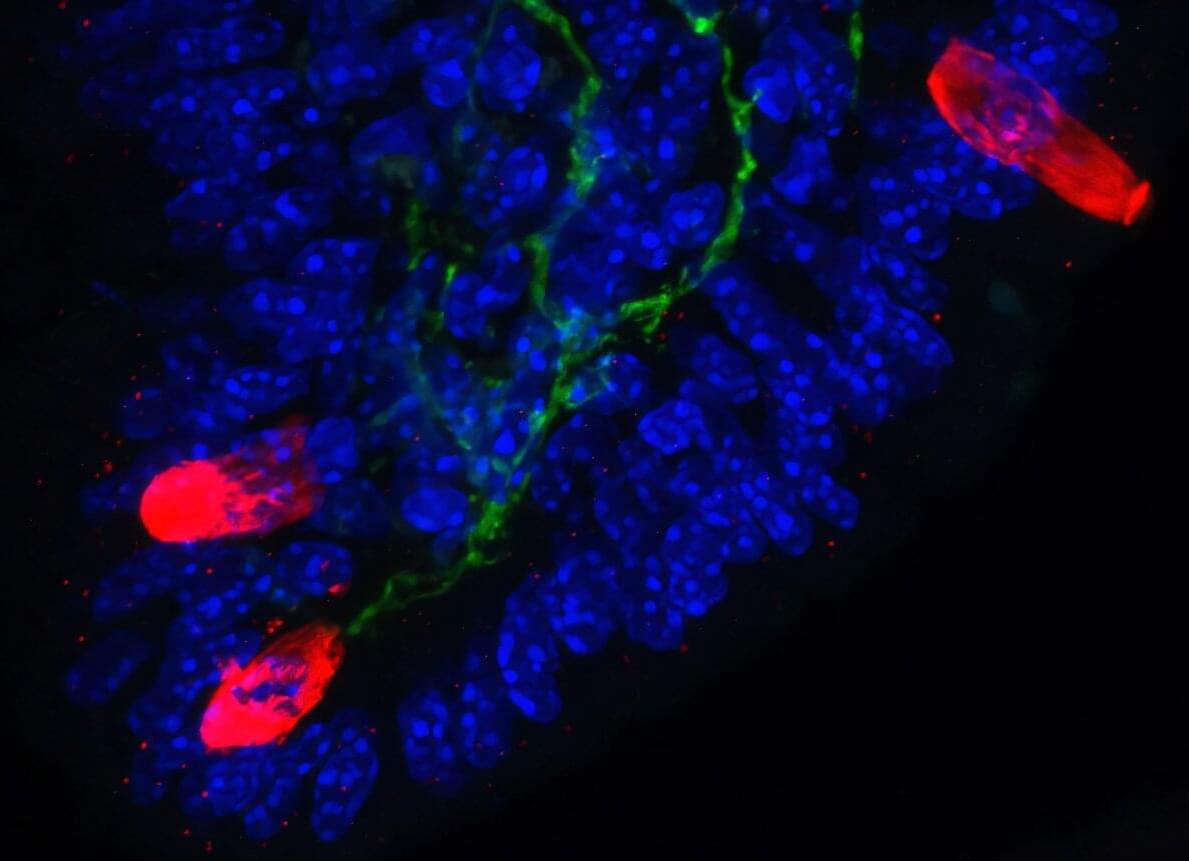

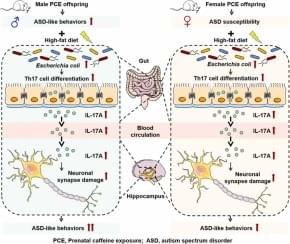

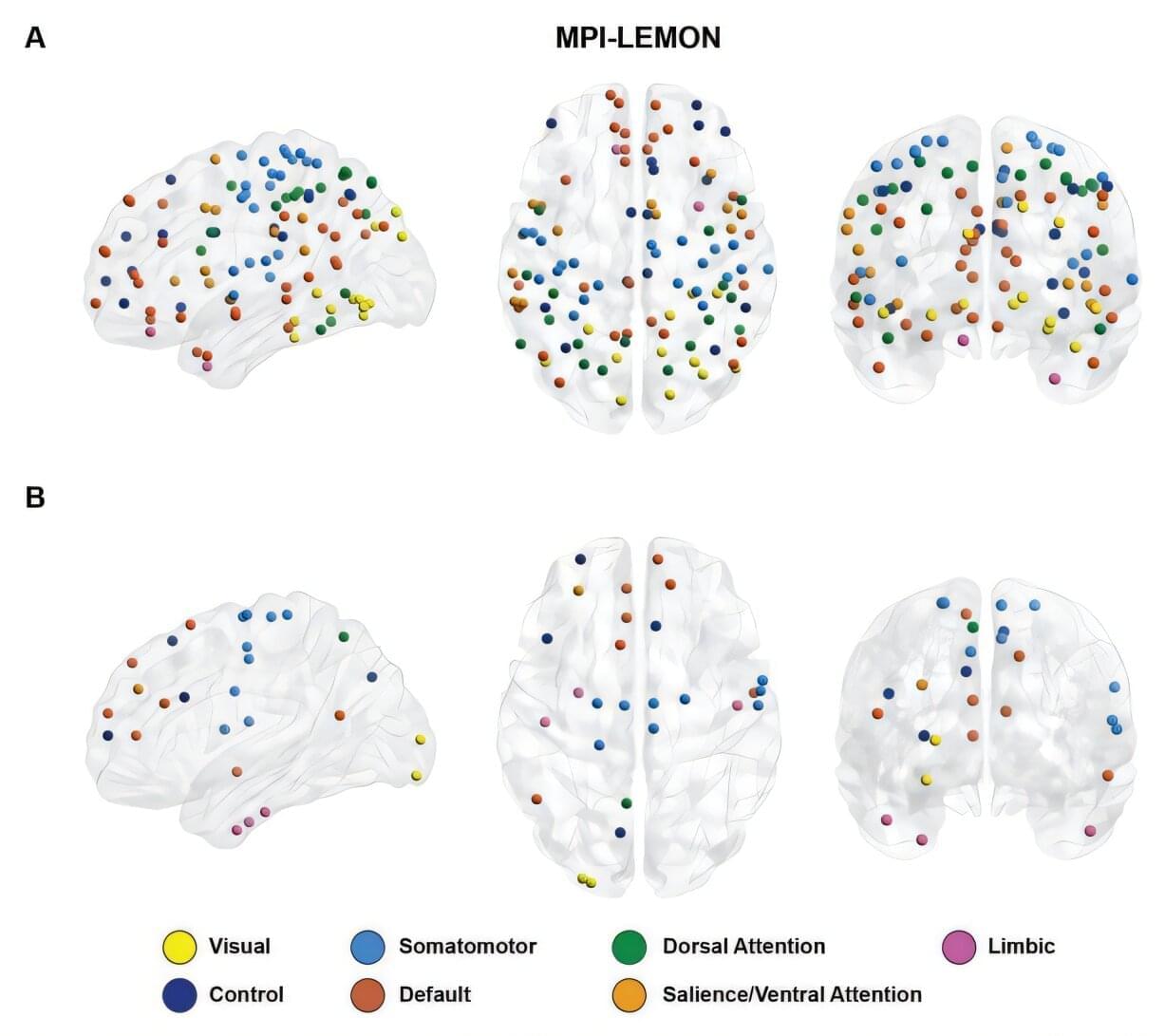

For more than a century, scientists have wondered why physical structures like blood vessels, neurons, tree branches, and other biological networks look the way they do. The prevailing theory held that nature simply builds these systems as efficiently as possible, minimizing the amount of material needed. But in the past, when researchers tested these networks against traditional mathematical optimization theories, the predictions consistently fell short.

The problem, it turns out, was that scientists were thinking in one dimension when they should have been thinking in three. “We were treating these structures like wire diagrams,” Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) physicist Xiangyi Meng, Ph.D., explains. “But they’re not thin wires, they’re three-dimensional physical objects with surfaces that must connect smoothly.”

This month, Meng and colleagues published a paper in the journal Nature showing that physical networks in living systems follow rules borrowed from an unlikely source: string theory, the exotic branch of physics that attempts to explain the fundamental structure of the universe.