Everything related to the human brain and neuroscience has always been an area in which specialists have said that there is much to discover, learn and investigate. In fact, the generation of memory in human beings, memories, and the different diseases that are clustered around the CPU of the body have always been constantly evolving.

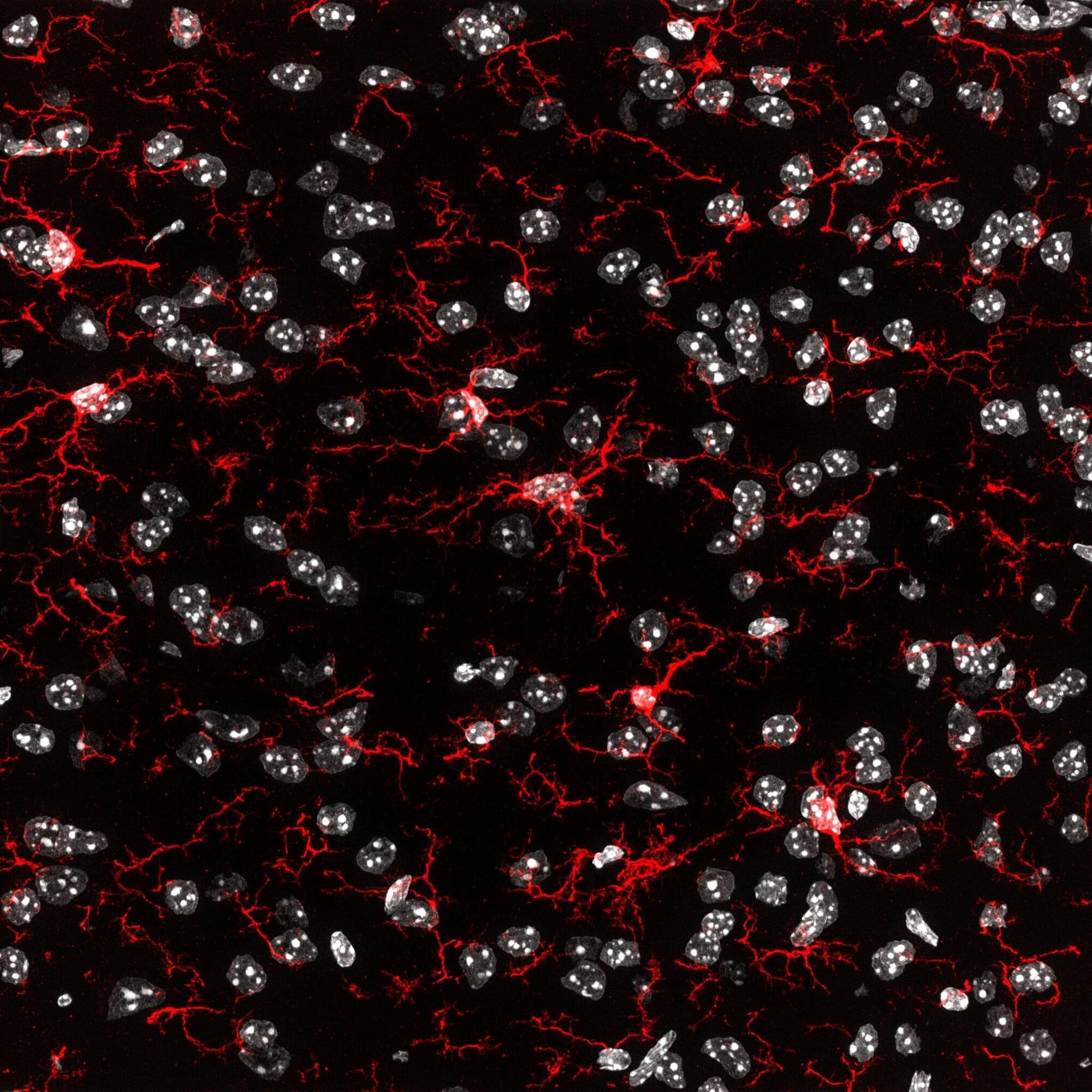

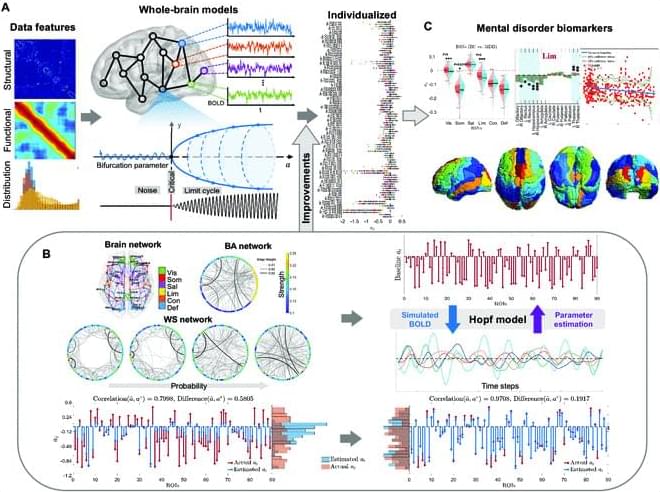

Now, Dr. Tomas Ryan of Trinity College Dublin, a neuroscientist who has explored the issues of brain learning by tracking the cells involved in this process, has found new findings suggesting that memory formation depends on the connections between groups of engram cells, neurons thought to capture and store distinct experiences.

In this new research, the experts indicate that each experience leaves a pattern of neuronal activation that can be activated later, which would mean the creation of a memory. To reach this conclusion, the neuroscientists tracked two sets of engram cells, each linked to a different memory.