The relationship between pathology in the brain and alterations in the gut microbiome could lead to therapies — even if it’s not clear which changes come first.

Back pain, migraines, arthritis, long-term concussion symptoms, complications following cancer treatment—these are just a few of the conditions linked to chronic pain, which affects 1 in 5 adults and for which medication is not always the answer.

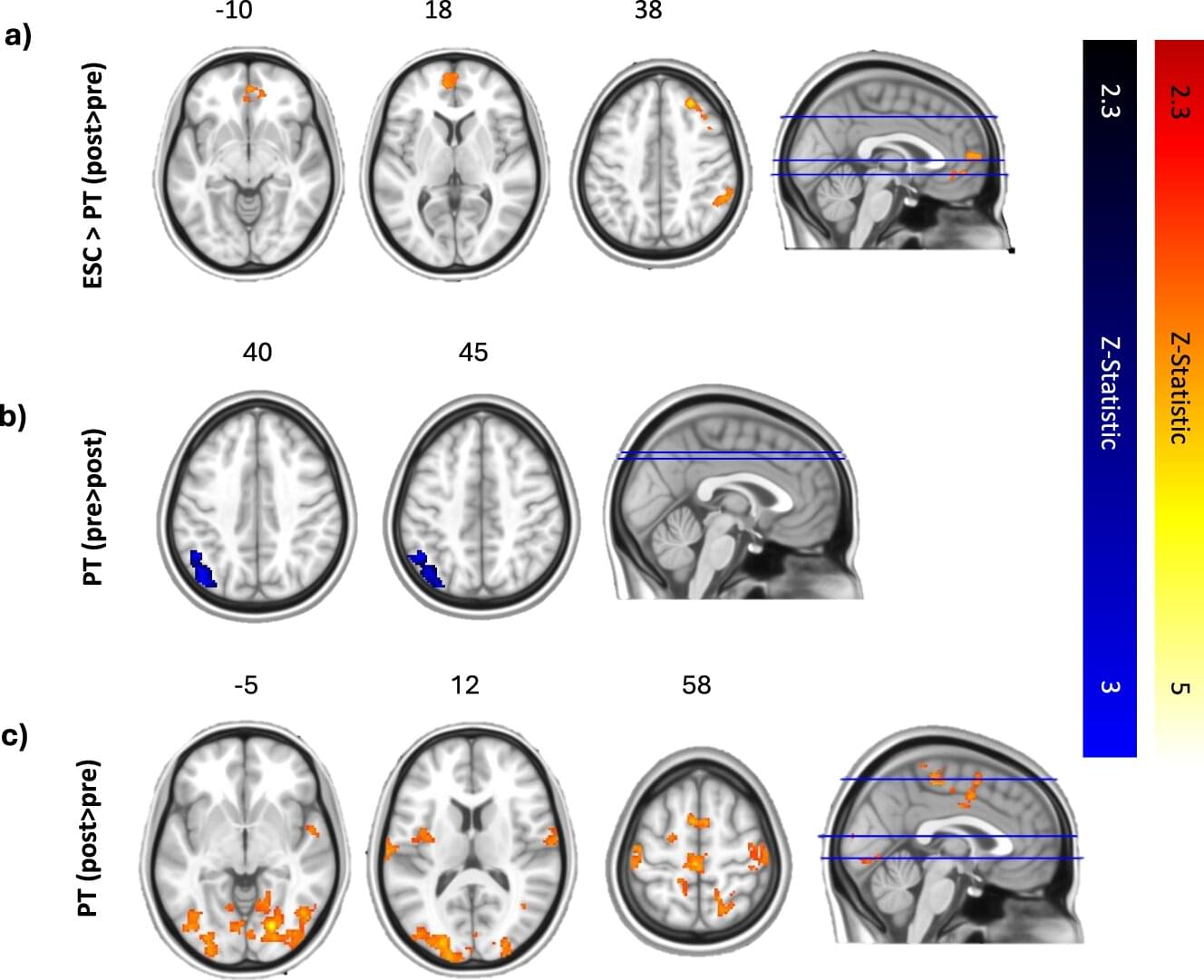

Now, a new review study offers insight into how specific types of psychological treatment can help relieve this pain through physical changes in the brain.

The research article was published today in The Lancet. The study was led by Professor Lene Vase from the Department of Psychology at Aarhus BSS, Aarhus University.

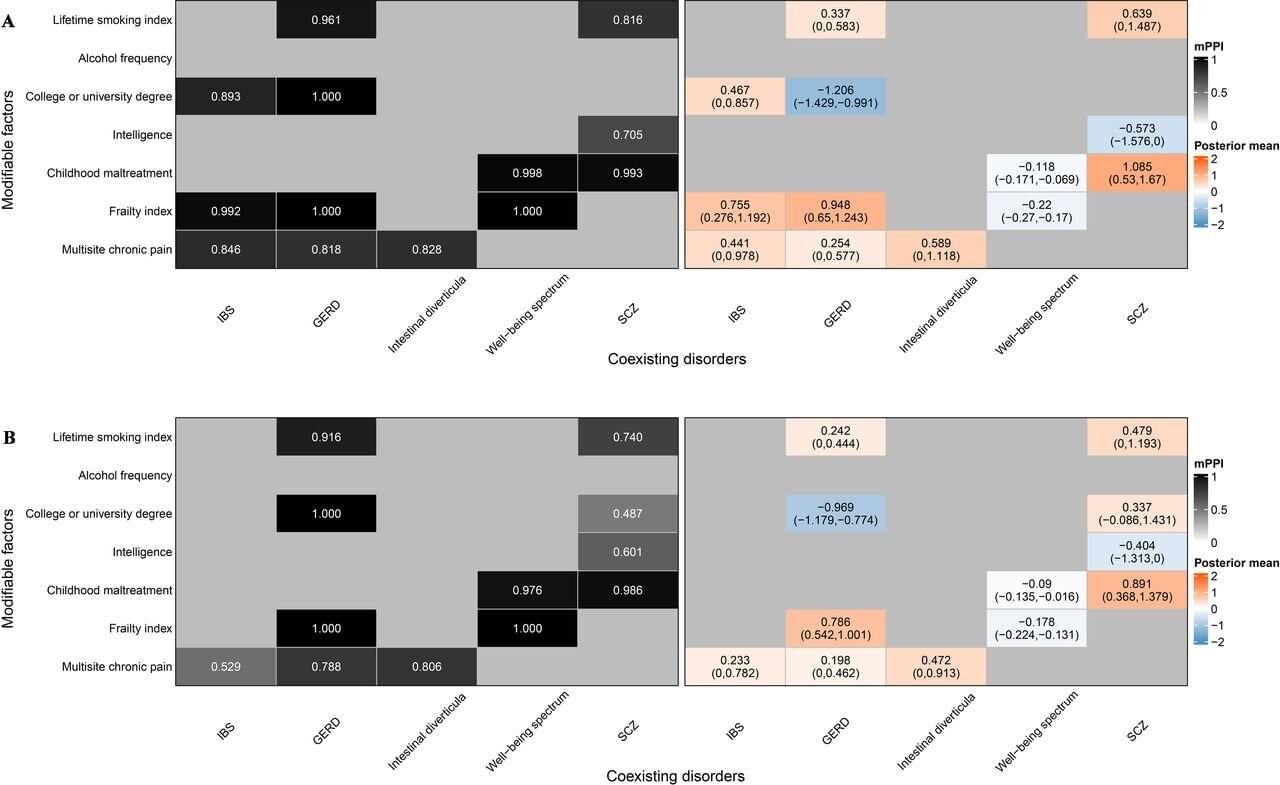

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent and debilitating gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately 5%–10% of the global population. Characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits, IBS imposes a significant burden on quality of life and health care systems worldwide.

Despite its prevalence, the exact pathogenesis of IBS remains elusive, and effective prevention strategies are lacking. Di Liu and colleagues conducted a comprehensive Mendelian randomization (MR) study—an approach that uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causality.

The study integrates Mendelian randomization (MR) and multiresponse MR (MR2) analyses to distinguish genuine causal relationships from shared or spurious associations. The research is published in the journal eGastroenterology.

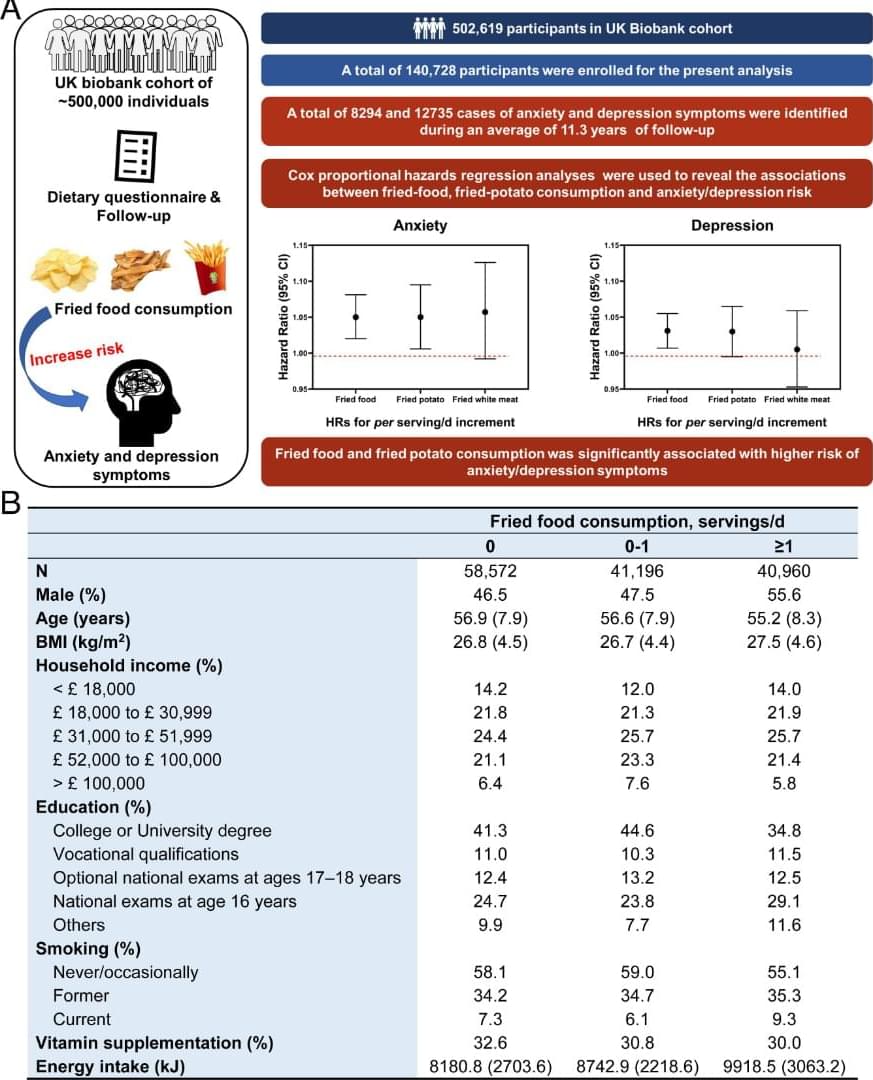

When zebrafish are relocated to a new environment, they seek protection by diving and staying at the safety home, until they feel safe enough to explore the unfamiliar environment (26). The swimming trajectories showed that zebrafish in the control group can swiftly explore and adapt to the novel environment, but chronic exposure to acrylamide reduces the ability to adapt to the unfamiliar environment (Fig. 3 A). Visualized heatmaps showed significant changes in swimming trajectories of zebrafish in the acrylamide exposure groups compared with those in the control group (Fig. 3 B). Furthermore, we found the swimming time and distance ratios in Zone 1 exhibited a dose-dependent decreasing trend in acrylamide exposure groups. Chronic exposure to acrylamide (0.5 mM) significantly decreased both swimming time and distance in Zone 1 and increased those in Zone 2 (Fig. 3 C and D). We recorded the novel object exploration test to visualize the behavioral alteration between the control and each acrylamide-treated group (Movie S3). The movie displays that zebrafish in the control group could swiftly explore and adapt to the novel environment, but chronic exposure to acrylamide reduced the ability to adapt to the unfamiliar environment, which indicated that acrylamide induces anxiety-and depressive-like behaviors by reducing exploration ability of zebrafish.

Moreover, the social preference test was used to assess sociality of zebrafish. Since the zebrafish are a group preference species, they frequently swim by forming a school and swim closely to one another (27). In the current social preference test, representative radar maps and visualized heatmaps exhibited significant changes of preference in swimming trajectories of zebrafish in acrylamide exposure groups compared to those in the control group, indicating that chronic exposure to acrylamide remarkably impairs the sociality of zebrafish (Fig. 3 E–G). For detailed parameters of behavioral trajectories, chronic exposure to acrylamide (0.5 mM) significantly increased both swimming time and distance ratios in the left zone and decreased those in the right zone (Fig. 3 H and I). Notably, chronic exposure to acrylamide (0.5 mM) significantly elevated traversing times and number of crossing the middle line (Fig. 3 J and K).

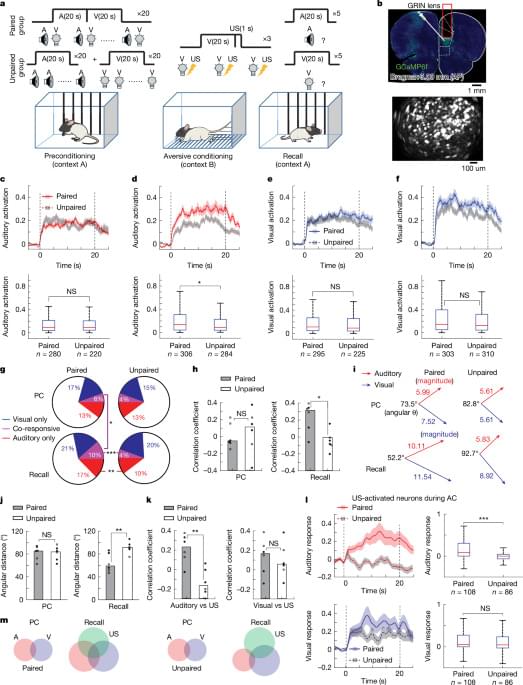

A Yale-led study shows that the senses stimulate a region of the brain that controls consciousness—a finding that might inform treatment for disorders related to attention, arousal, and more.

Humans perceive and navigate the world around us with the help of our five senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. And while scientists have long known that these different senses activate different parts of the brain, a new Yale-led study indicates that multiple senses all stimulate a critical region deep in the brain that controls consciousness.

The study, published in the journal NeuroImage, sheds new light on how sensory perception works in the brain and may fuel the development of therapies to treat disorders involving attention, arousal, and consciousness.

Depression is among the most widespread mental health disorders worldwide, typically characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, a lack of interest in daily activities and dysregulated sleep and/or eating habits. There are now a wide range of pharmacological treatments for depression, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants and atypical antidepressants.

In recent years, some research groups have been exploring the potential of alternative treatments for depression that rely on psychedelic compounds, such as psilocybin. Psilocybin is a compound naturally found in more than 100 species of mushrooms, which can influence the mood and perceptions of those who ingest it.

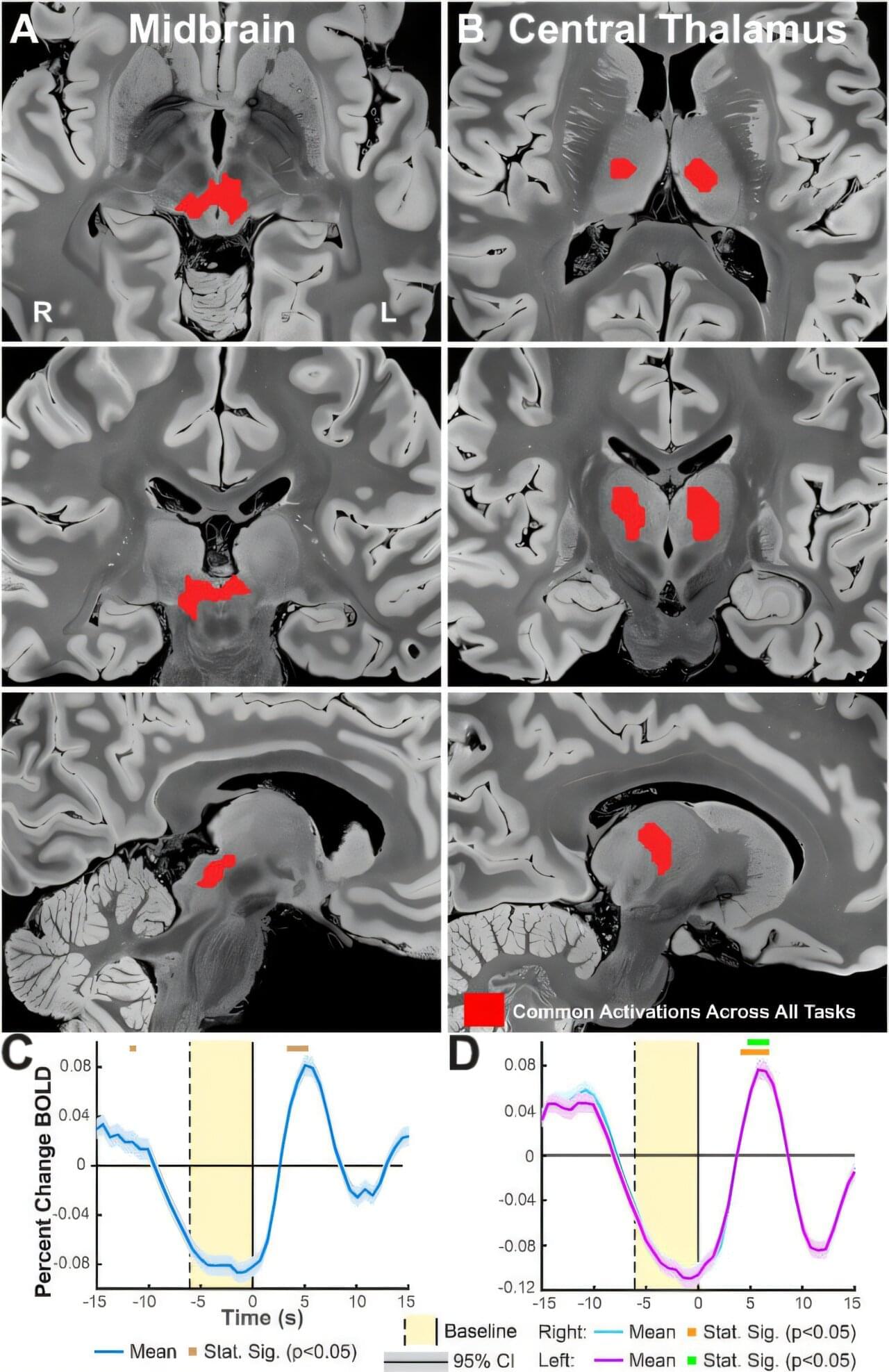

Researchers at Imperial College London’s Center for Psychedelic Research recently carried out a study aimed at better understanding the effects of psilocybin treatment on the processing of music and the experience of emotions, comparing them to those of escitalopram, a widely used SSRI.