Our brains don’t just remember what we see and hear, they fuse the two into cohesive memories.

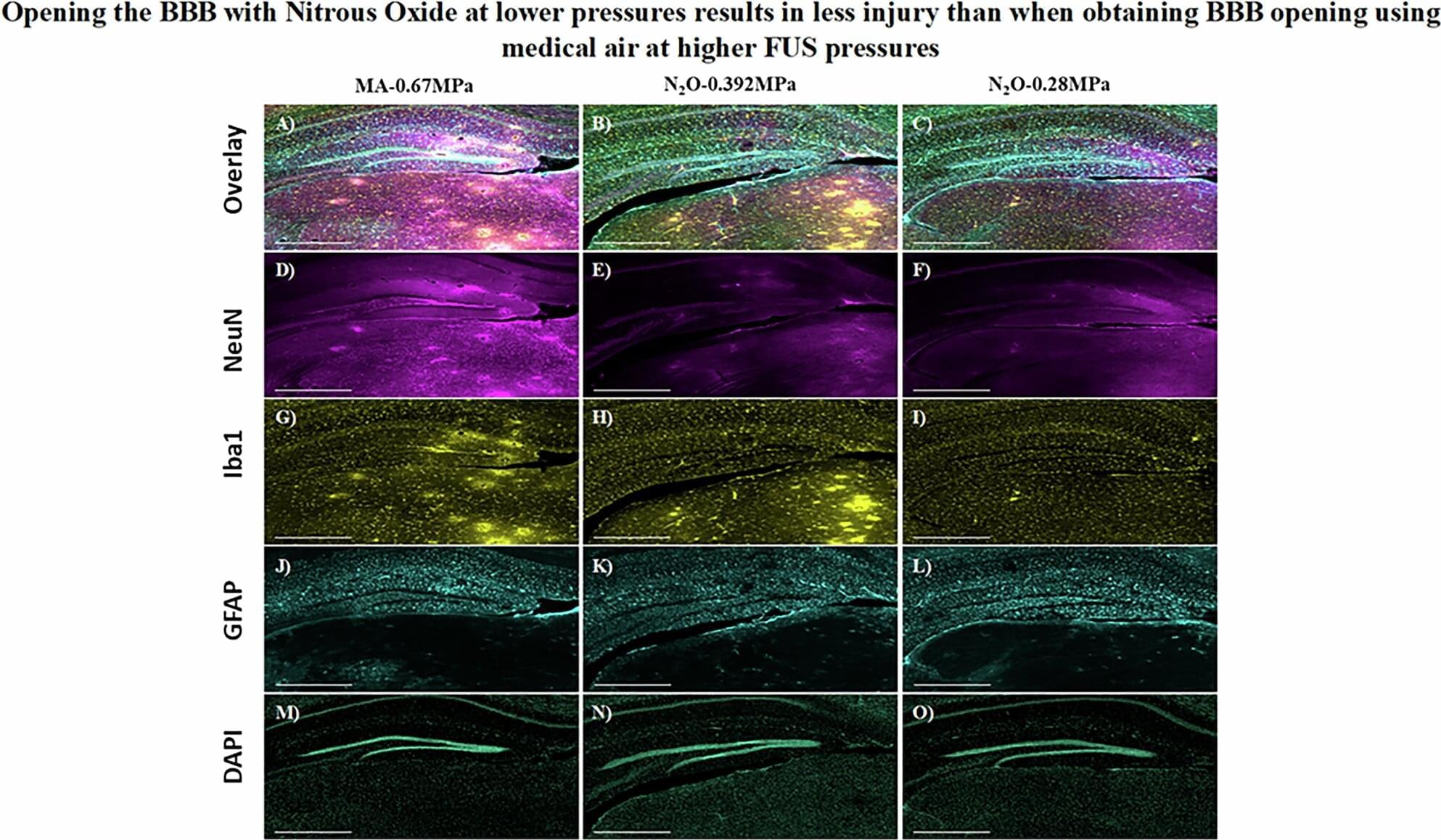

Nitrous oxide, a commonly used analgesic gas, temporarily improved the opening of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to allow gene therapy delivery in mouse models using focused ultrasound (FUS), UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers report in a new study. Their findings, published in Gene Therapy, could eventually lead to new ways to treat a variety of brain diseases and disorders.

“The approach we explored in this study has the potential to advance care for diseases of the brain that can be treated by targeted therapeutic delivery,” said study leader Bhavya R. Shah, M.D., Associate Professor of Radiology, Neurological Surgery, and in the Advanced Imaging Research Center at UT Southwestern. He’s also an Investigator in the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute and a member of the Center for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Deepshikha Bhardwaj, Ph.D., Senior Research Associate at UTSW, was the study’s first author.

The BBB is a highly selective border of semipermeable cells that line tiny blood vessels supplying blood to the brain. It is thought to have developed during evolution to protect the brain from toxins and infections in the blood. However, the BBB also impedes the delivery of drugs that could be used to treat neurologic or neuropsychiatric conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or brain tumors. Consequently, researchers have worked for decades to develop solutions that can temporarily open the BBB to allow treatments to enter.

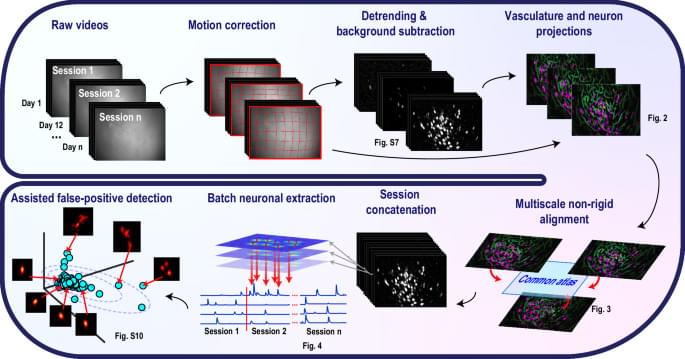

Neural data analysis algorithms capable of tracking neuronal signals from one-photon functional imaging data longitudinally and reliably are still lacking. Here authors developed CaliAli, a tool for extracting calcium signals across multiple days. Validated with optogenetic tagging, dual-color imaging, and place cell data, CaliAli demonstrated stable neuron tracking for up to 99 days.

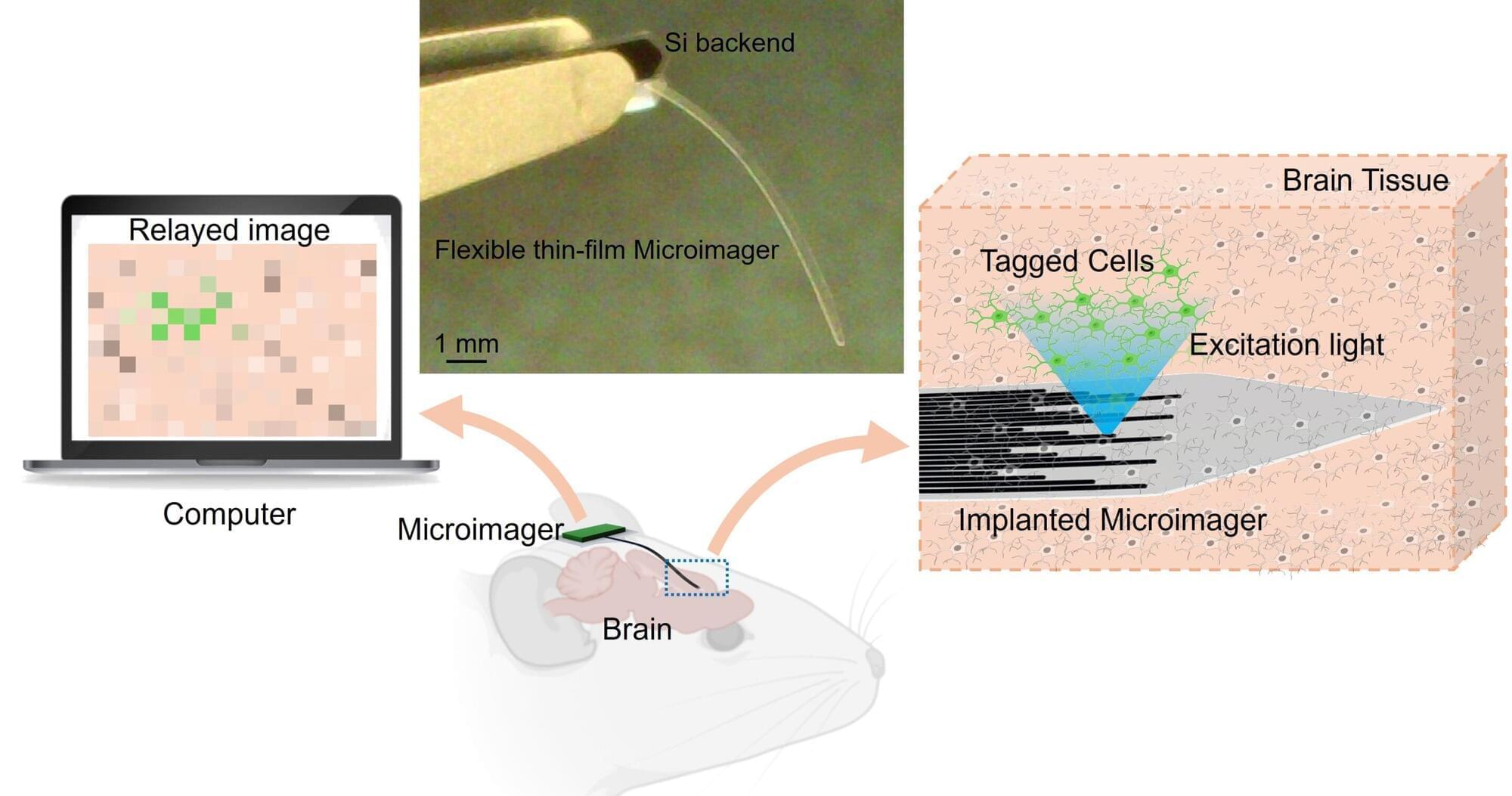

Researchers have developed an extremely thin, flexible imager that could be useful for noninvasively acquiring images from inside the body. The new technology could one day enable early and precise disease detection, providing critical insights to guide timely and effective treatment.

“As opposed to existing prohibitively large endoscopes made of cameras and optical lenses or bulky fiber optic bundles, our microimager is very compact,” said research team leader Maysam Chamanzar from Carnegie Mellon University. “Much thinner than a typical eyelash, our device is ideal for reaching deep regions of the body without causing significant damage to the tissue.”

In the journal Biomedical Optics Express, the researchers showed that the microimager, which is only 7 microns thick—a tenth of an eyelash diameter—and about 10 mm long, can be used in a mouse brain for structural and functional imaging of brain activity. The width of the thin film imager can be customized based on the desired field of view and resolution.

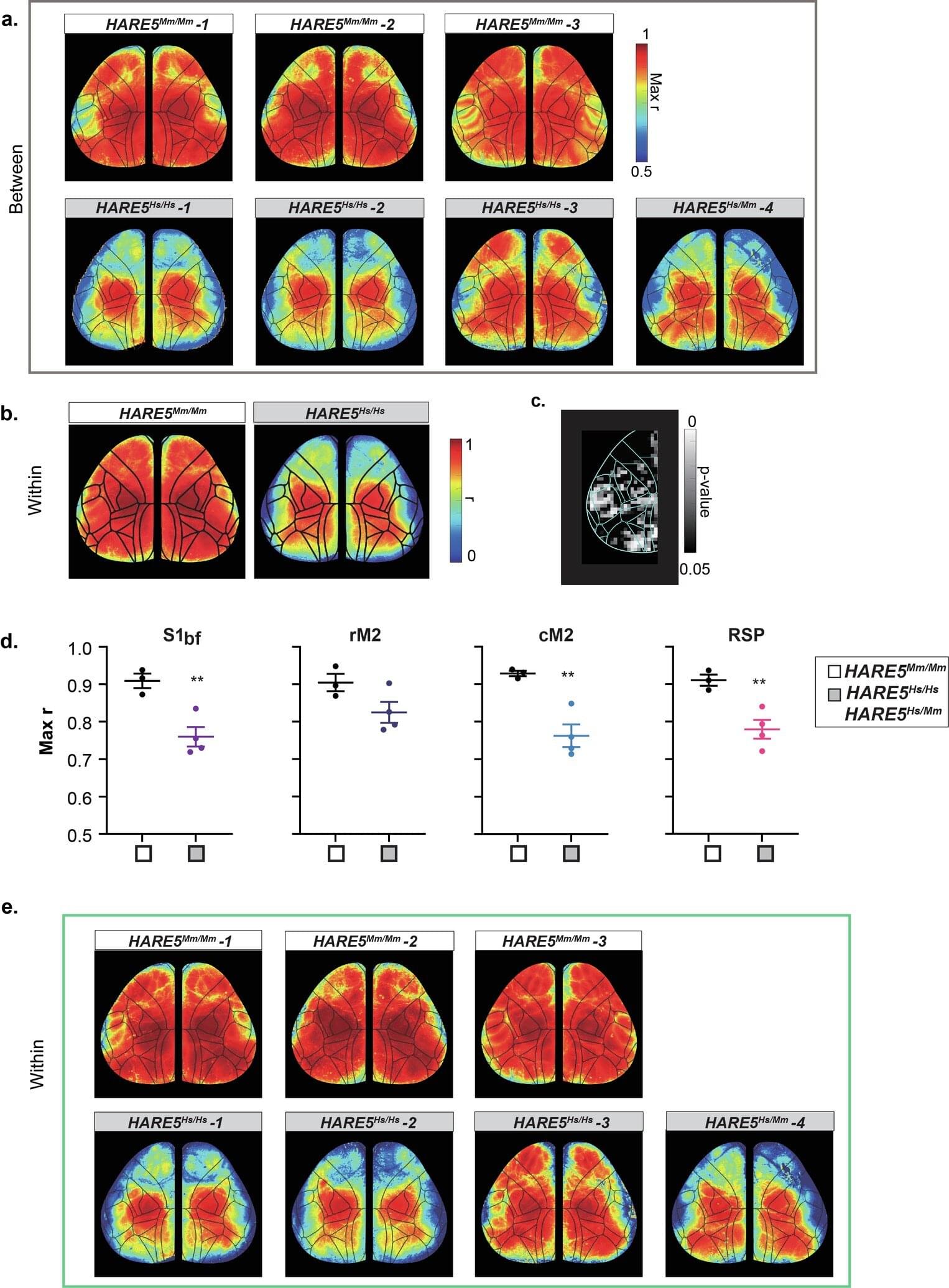

Duke University Medical Center-led research has identified a human-specific DNA enhancer that regulates neural progenitor proliferation and cortical size. Small genetic changes in HARE5 amplify a key developmental pathway, resulting in increased cortical size and neuron number in experimental models. Findings have implications for understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental disorders.

Humans possess a significantly larger and more complex cerebral cortex compared to other species, contributing to advanced cognitive functions. Comparative genomics research has identified Human Accelerated Regions (HARs), segments of non-coding DNA with human-specific genetic changes. Many HARs are located near genes associated with brain development and neural differentiation.

Because thousands of HARs have been identified and linked to brain-related genes, the next critical step is to investigate how these regulatory elements actively shape human brain features.

The study revealed genes and cellular pathways that haven’t been linked to Alzheimer’s before, including one involved in DNA repair. Identifying new drug targets is critical because many of the Alzheimer’s drugs that have been developed to this point haven’t been as successful as hoped.

Working with researchers at Harvard Medical School, the team used data from humans and fruit flies to identify cellular pathways linked to neurodegeneration. This allowed them to identify additional pathways that may be contributing to the development of Alzheimer’s.

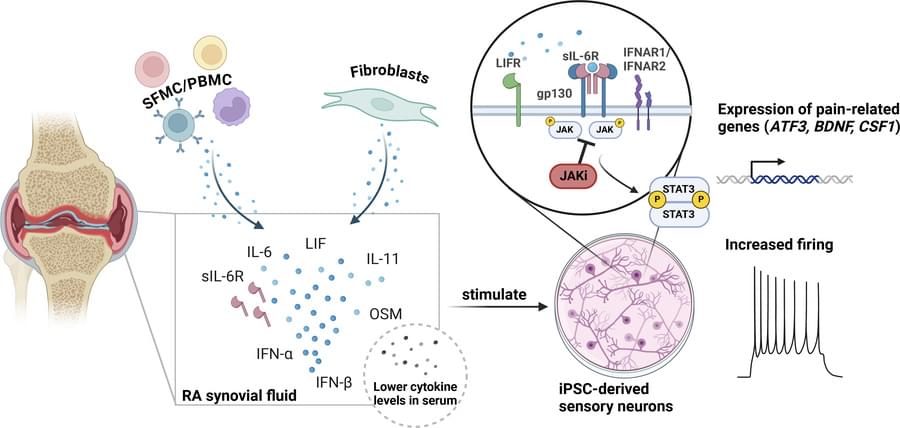

Anti-inflammatory drug JAK inhibitors (JAKi) reduces pain in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) but the mechanism is not clear.

To figure out if JAKi directly acted on human sensory neurons, the authors found they expressed JAK1 and STAT3.

The show that RA synovial fluid addition to human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived sensory neurons led to phosphorylation of STAT3 (pSTAT3), which was completely blocked by the JAKi tofacitinib.

The researchers also discovered that RA synovial fluid was enriched for the STAT3 signalling cytokines IL-6, IL-11, LIF, IFN-alpha and IFN-beta, and their requisite receptors present in peripheral nerves post-mortem.

They observed upregulation of pain-relevant genes with STAT3-binding sites, an effect which was blocked by tofacitinib in cytokine treated iPSCs. LIF also induced neuronal sensitisation, highlighting this molecule as a putative pain mediator.

Tofacitinib reduced the firing rate of sensory neurons stimulated with RA synovial fluid indicating role for JAKi in controlling analgesic properties. https://sciencemission.com/RA-synovial-fluid-induces-JAK-dep…tivation-o