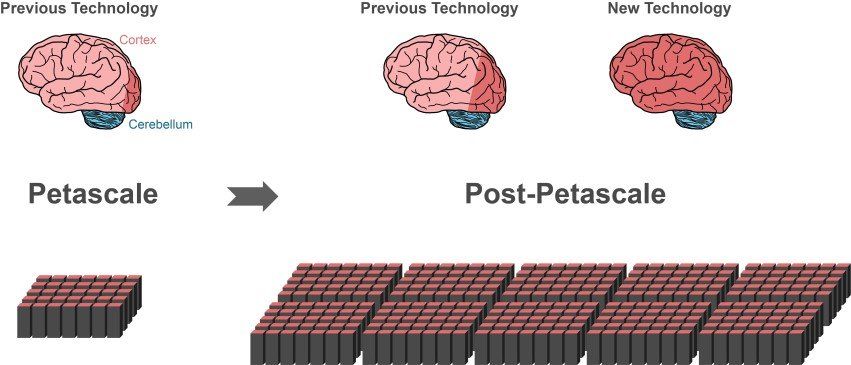

An international group of researchers has made a decisive step towards creating the technology to achieve simulations of brain-scale networks on future supercomputers of the exascale class. The breakthrough, published in Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, allows larger parts of the human brain to be represented, using the same amount of computer memory. Simultaneously, the new algorithm significantly speeds up brain simulations on existing supercomputers.

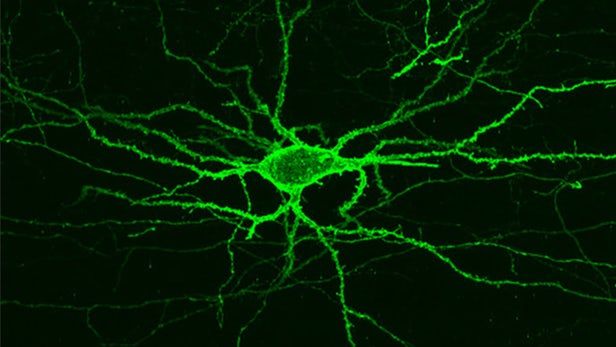

The human brain is an organ of incredible complexity, composed of 100 billion interconnected nerve cells. However, even with the help of the most powerful supercomputers available, it is currently impossible to simulate the exchange of neuronal signals in networks of this size.

“Since 2014, our software can simulate about one percent of the neurons in the human brain with all their connections,” says Markus Diesmann, Director at the Jülich Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine (INM-6). In order to achieve this impressive feat, the software requires the entire main memory of petascale supercomputers, such as the K computer in Kobe and JUQUEEN in Jülich.