Cadmium-based nanostructures are opening new possibilities in near-infrared (NIR) technology, from medical imaging to fiber optics and solar energy.

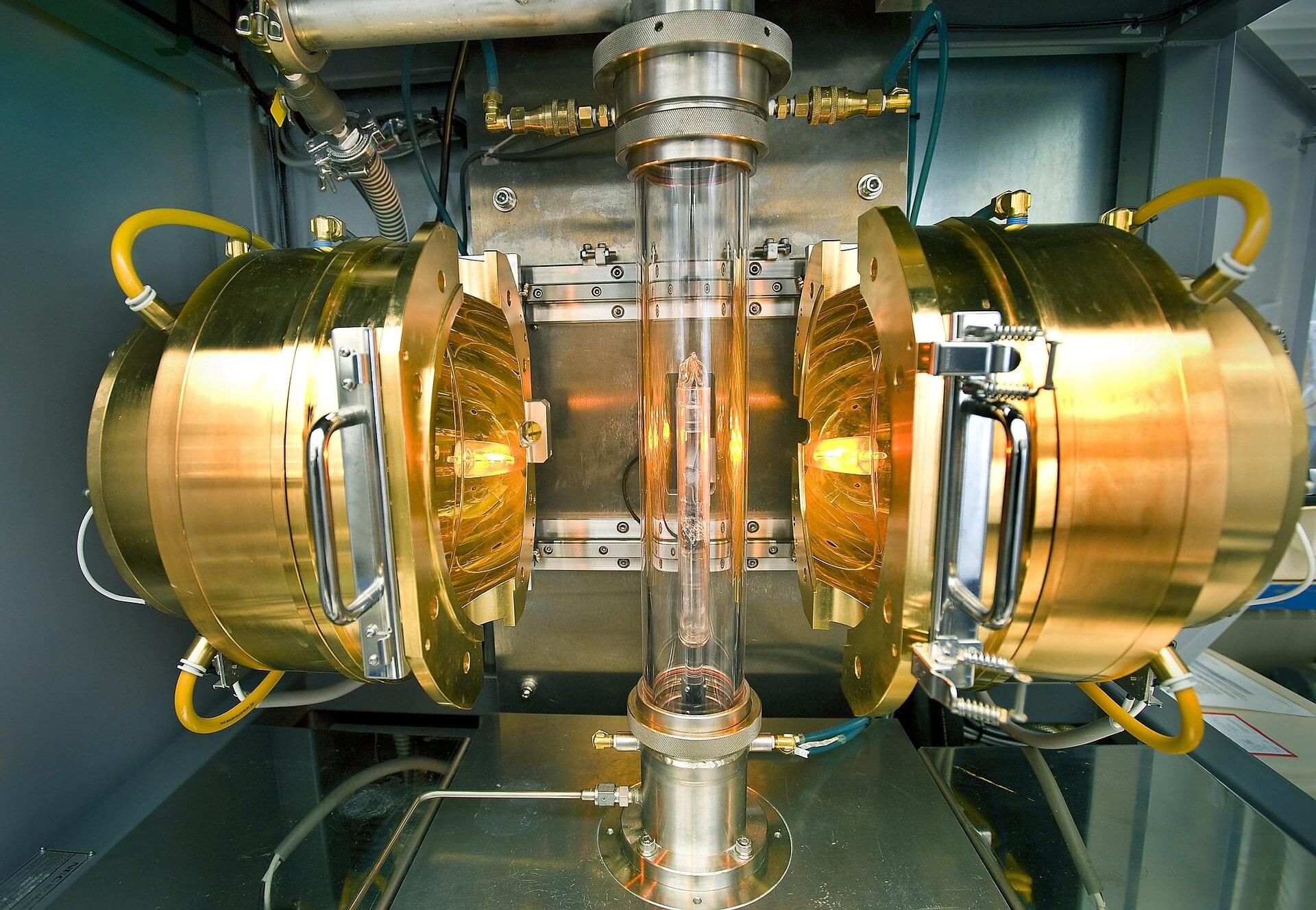

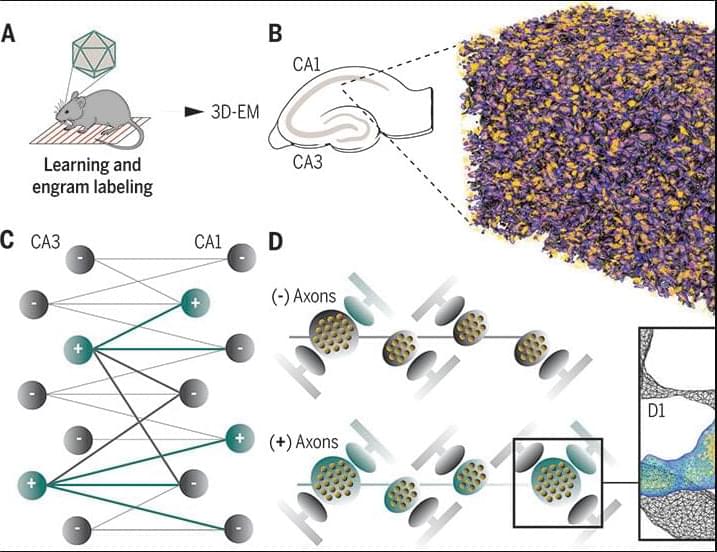

A major challenge in their development is controlling their atomic structure with precision, which researchers at HZDR and TU Dresden tackled using cation exchange. This technique allows for precise manipulation of nanostructure composition, unlocking new optical and electronic properties. The research highlights the crucial role of active corners and defects, which influence charge transport and light absorption. By linking these nanostructures into organized systems, scientists are paving the way for self-assembling materials with advanced functions, from improved sensors to next-generation electronics.

Harnessing Near-Infrared Light with Cadmium-Based Nanostructures.