At the threshold of a century poised for unprecedented transformations, we find ourselves at a crossroads unlike any before. The convergence of humanity and technology is no longer a distant possibility; it has become a tangible reality that challenges our most fundamental conceptions of what it means to be human.

This article seeks to explore the implications of this new era, in which Artificial Intelligence (AI) emerges as a central player. Are we truly on the verge of a symbiotic fusion, or is the conflict between the natural and the artificial inevitable?

The prevailing discourse on AI oscillates between two extremes: on one hand, some view this technology as a powerful extension of human capabilities, capable of amplifying our creativity and efficiency. On the other, a more alarmist narrative predicts the decline of human significance in the face of relentless machine advancement. Yet, both perspectives seem overly simplistic when confronted with the intrinsic complexity of this phenomenon. Beyond the dichotomy of utopian optimism and apocalyptic pessimism, it is imperative to critically reflect on AI’s cultural, ethical, and philosophical impact on the social fabric, as well as the redefinition of human identity that this technological revolution demands.

Since the dawn of civilization, humans have sought to transcend their natural limitations through the creation of tools and technologies. From the wheel to the modern computer, every innovation has been seen as a means to overcome the physical and cognitive constraints imposed by biology. However, AI represents something profoundly different: for the first time, we are developing systems that not only execute predefined tasks but also learn, adapt, and, to some extent, think.

This transition should not be underestimated. While previous technologies were primarily instrumental—serving as controlled extensions of human will—AI introduces an element of autonomy that challenges the traditional relationship between subject and object. Machines are no longer merely passive tools; they are becoming active partners in the processes of creation and decision-making. This qualitative leap radically alters the balance of power between humans and machines, raising crucial questions about our position as the dominant species.

But what does it truly mean to “be human” in a world where the boundaries between mind and machine are blurring? Traditionally, humanity has been defined by attributes such as consciousness, emotion, creativity, and moral decision-making. Yet, as AI advances, these uniquely human traits are beginning to be replicated—albeit imperfectly—within algorithms. If a machine can imitate creativity or exhibit convincing emotional behavior, where does our uniqueness lie?

This challenge is not merely technical; it strikes at the core of our collective identity. Throughout history, humanity has constructed cultural and religious narratives that placed us at the center of the cosmos, distinguishing us from animals and the forces of nature. Today, that narrative is being contested by a new technological order that threatens to displace us from our self-imposed pedestal. It is not so much the fear of physical obsolescence that haunts our reflections but rather the anxiety of losing the sense of purpose and meaning derived from our uniqueness.

Despite these concerns, many AI advocates argue that the real opportunity lies in forging a symbiotic partnership between humans and machines. In this vision, technology is not a threat to humanity but an ally that enhances our capabilities. The underlying idea is that AI can take on repetitive or highly complex tasks, freeing humans to engage in activities that truly require creativity, intuition, and—most importantly—emotion.

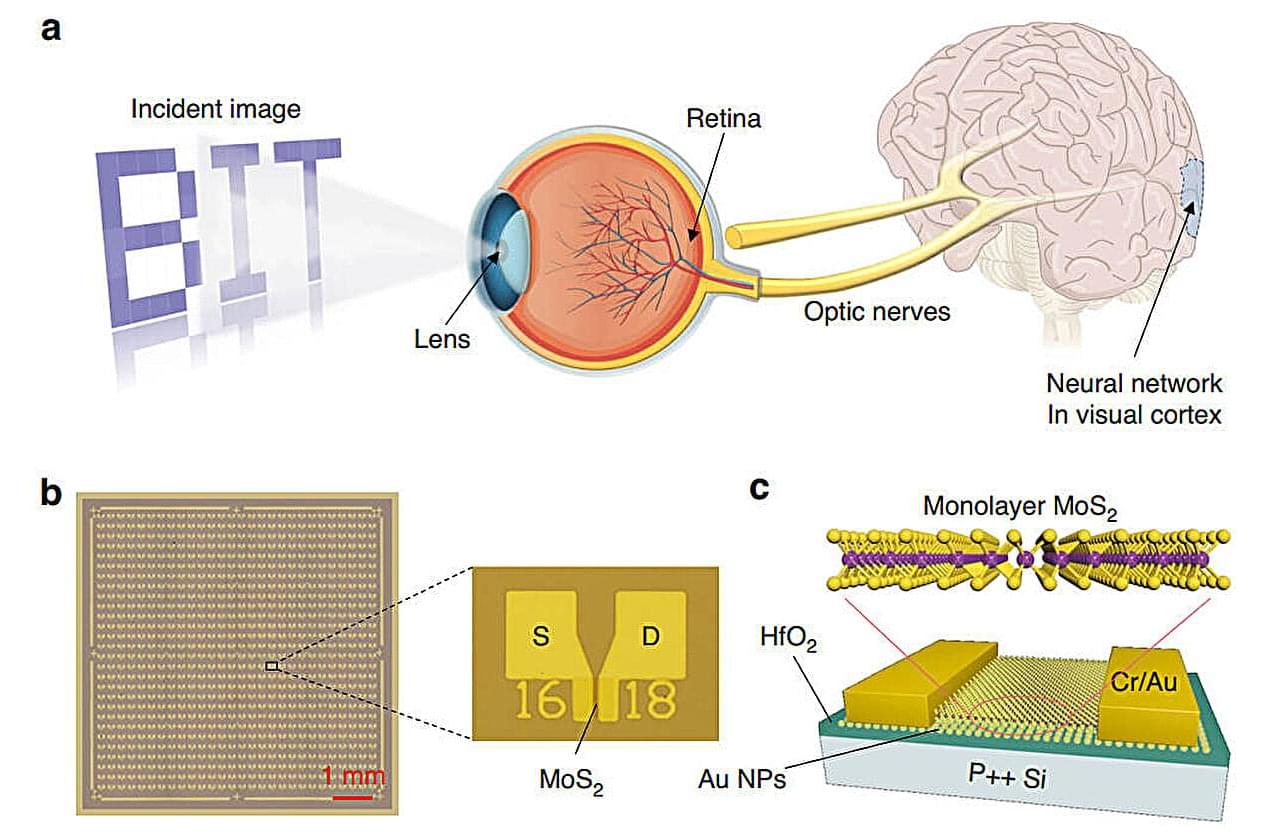

Concrete examples of this approach can already be seen across various sectors. In medicine, AI-powered diagnostic systems can process vast amounts of clinical data in record time, allowing doctors to focus on more nuanced aspects of patient care. In the creative industry, AI-driven text and image generation software are being used as sources of inspiration, helping artists and writers explore new ideas and perspectives. In both cases, AI acts as a catalyst, amplifying human abilities rather than replacing them.

Furthermore, this collaboration could pave the way for innovative solutions in critical areas such as environmental sustainability, education, and social inclusion. For example, powerful neural networks can analyze global climate patterns, assisting scientists in predicting and mitigating natural disasters. Personalized algorithms can tailor educational content to the specific needs of each student, fostering more effective and inclusive learning. These applications suggest that AI, far from being a destructive force, can serve as a powerful instrument to address some of the greatest challenges of our time.

However, for this vision to become reality, a strategic approach is required—one that goes beyond mere technological implementation. It is crucial to ensure that AI is developed and deployed ethically, respecting fundamental human rights and promoting collective well-being. This involves regulating harmful practices, such as the misuse of personal data or the indiscriminate automation of jobs, as well as investing in training programs that prepare people for the new demands of the labor market.

While the prospect of symbiotic fusion is hopeful, we cannot ignore the inherent risks of AI’s rapid evolution. As these technologies become more sophisticated, so too does the potential for misuse and unforeseen consequences. One of the greatest dangers lies in the concentration of power in the hands of a few entities, whether they be governments, multinational corporations, or criminal organizations.

Recent history has already provided concerning examples of this phenomenon. The manipulation of public opinion through algorithm-driven social media, mass surveillance enabled by facial recognition systems, and the use of AI-controlled military drones illustrate how this technology can be wielded in ways that undermine societal interests.

Another critical risk in AI development is the so-called “alignment problem.” Even if a machine is programmed with good intentions, there is always the possibility that it misinterprets its instructions or prioritizes objectives that conflict with human values. This issue becomes particularly relevant in the context of autonomous systems that make decisions without direct human intervention. Imagine, for instance, a self-driving car forced to choose between saving its passenger or a pedestrian in an unavoidable collision. How should such decisions be made, and who bears responsibility for the outcome?

These uncertainties raise legitimate concerns about humanity’s ability to maintain control over increasingly advanced technologies. The very notion of scientific progress is called into question when we realize that accumulated knowledge can be used both for humanity’s benefit and its detriment. The nuclear arms race during the Cold War serves as a sobering reminder of what can happen when science escapes moral oversight.

Whether the future holds symbiotic fusion or inevitable conflict, one thing is clear: our understanding of human identity must adapt to the new realities imposed by AI. This adjustment will not be easy, as it requires confronting profound questions about free will, the nature of consciousness, and the essence of individuality.

One of the most pressing challenges is reconciling our increasing technological dependence with the preservation of human dignity. While AI can significantly enhance quality of life, there is a risk of reducing humans to mere consumers of automated services. Without a conscious effort to safeguard the emotional and spiritual dimensions of human experience, we may end up creating a society where efficiency outweighs empathy, and interpersonal interactions are replaced by cold, impersonal digital interfaces.

On the other hand, this very transformation offers a unique opportunity to rediscover and redefine what it means to be human. By delegating mechanical and routine tasks to machines, we can focus on activities that truly enrich our existence—art, philosophy, emotional relationships, and civic engagement. AI can serve as a mirror, compelling us to reflect on our values and aspirations, encouraging us to cultivate what is genuinely unique about the human condition.

Ultimately, the fate of our relationship with AI will depend on the choices we make today. We can choose to view it as an existential threat, resisting the inevitable changes it brings, or we can embrace the challenge of reinventing our collective identity in a post-humanist era. The latter, though more daring, offers the possibility of building a future where technology and humanity coexist in harmony, complementing each other.

To achieve this, we must adopt a holistic approach that integrates scientific, ethical, philosophical, and sociological perspectives. It also requires an open, inclusive dialogue involving all sectors of society—from researchers and entrepreneurs to policymakers and ordinary citizens. After all, AI is not merely a technical tool; it is an expression of our collective imagination, a reflection of our ambitions and fears.

As we gaze toward the horizon, we see a world full of uncertainties but also immense possibilities. The future is not predetermined; it will be shaped by the decisions we make today. What kind of social contract do we wish to establish with AI? Will it be one of domination or cooperation? The answer to this question will determine not only the trajectory of technology but the very essence of our existence as a species.

Now is the time to embrace our historical responsibility and embark on this journey with courage, wisdom, and an unwavering commitment to the values that make human life worth living.

__

Copyright © 2025, Henrique Jorge

[ This article was originally published in Portuguese in SAPO’s technology section at: https://tek.sapo.pt/opiniao/artigos/a-sinfonia-do-amanha-tit…exao-seria ]