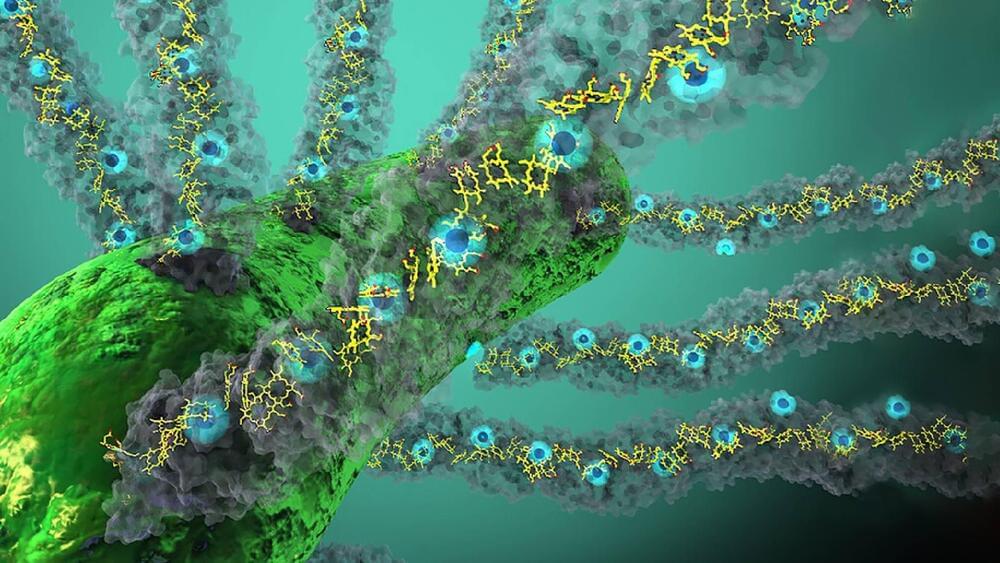

Engineers at EPFL have found a way to insert carbon nanotubes into photosynthetic bacteria, which greatly improves their electrical output. They even pass these nanotubes down to their offspring when they divide, through what the team calls “inherited nanobionics.”

Solar cells are the leading source of renewable energy, but their production has a large environmental footprint. As with many things, we can take cues from nature about how to improve our own devices, and in this case photosynthetic bacteria, which get their energy from sunlight, could be used in microbial fuel cells.

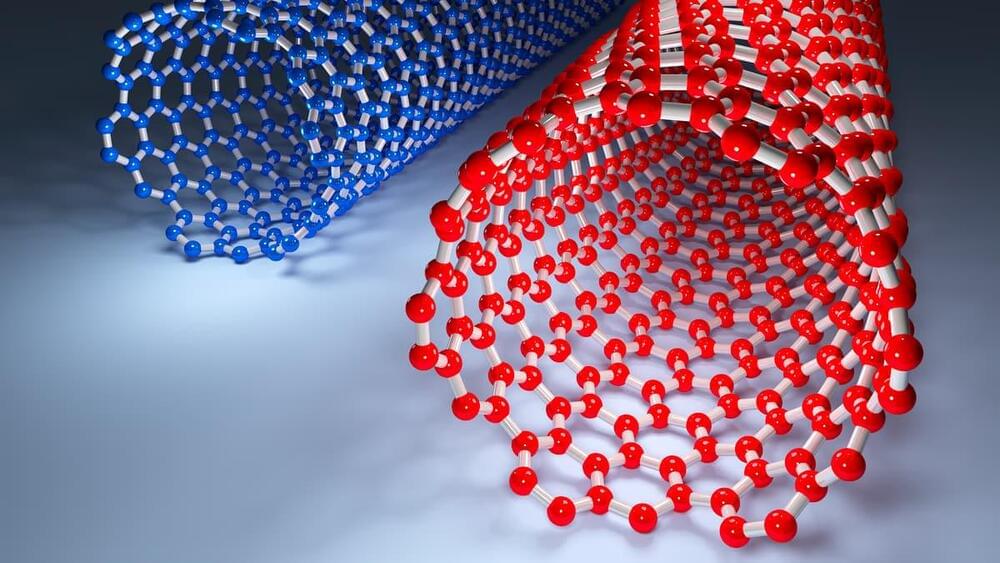

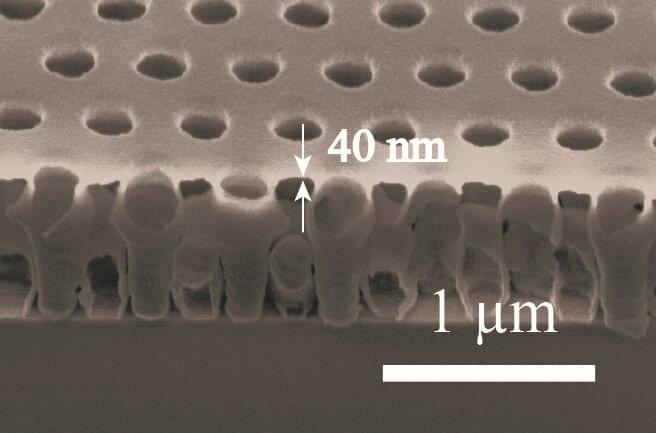

In the new study, the EPFL team gave these bacteria a boost by inserting carbon nanotubes – tiny rolled-up sheets of graphene, a material that’s famously conductive. The nanotube-loaded bugs were able to produce up to 15 times more electricity than their non-edited counterparts from the same amount of sunlight.