The U.S. military is spending millions on an advanced implant that would allow a human brain to communicate directly with computers.

If it succeeds, cyborgs will be a reality.

A cognitive neuroscientist and his team at HRL Laboratories in Malibu, California, seem to have achieved the impossible.

According to a press release, the team “measured the brain activity patterns of six commercial and military pilots, and then transmitted these patterns into novice subjects as they learned to pilot an airplane in a realistic flight simulator.”

Reserve you calendars for March 9th because New America’s Cybersecurity Initiative is hosting its annual Cybersecurity for a New America Conference in Washington, D.C.

On Wednesday, March 9, New America’s Cybersecurity Initiative will host its annual Cybersecurity for a New America Conference in Washington, D.C. This year’s conference will focus on securing the future cyberspace. For more information and to RSVP, visit the New America website.

So, what does cyberwar mean anyway?

At core, when we talk about cyberwar, we’re just talking about warfare conducted through computers and other electronic devices, typically over the Internet. As the very ’90s prefix cyber– (when was the last time you heard someone talk about cyberspace with a straight face?) suggests, it’s been part of our cultural and political conversations since the early ’80s. In recent years, however, such conversations have picked up as those in power become more conscious of our reliance on computers—and our consequent vulnerability. Perhaps more importantly, information like that disclosed by Edward Snowden has demonstrated that governments have already made preparations for virtual conflict, whether or not they’re actively engaging in it now. (Click here for a cheat sheet.)

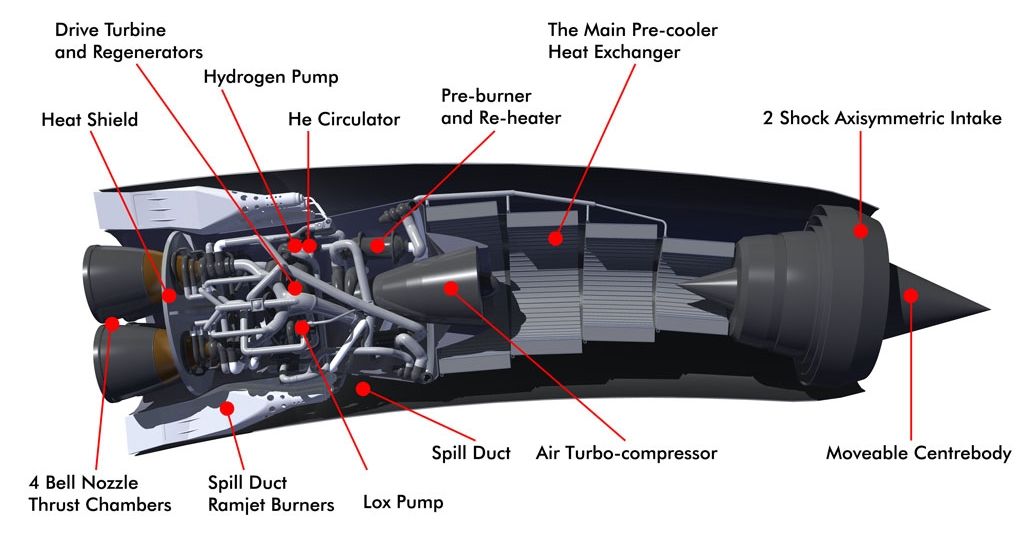

Within the next year, the U.S. Air Force plans to unveil novel spacecraft concepts that would be powered by a potentially revolutionary reusable engine designed for a private space plane.

plans to unveil novel spacecraft concepts that would be powered by a potentially revolutionary reusable engine designed for a private space plane.

Since January 2014, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) has been developing hypersonic vehicle concepts that use the Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine (SABRE), which was invented by England-based Reaction Engines Ltd. and would propel the company’s Skylon space plane.

(AFRL) has been developing hypersonic vehicle concepts that use the Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine (SABRE), which was invented by England-based Reaction Engines Ltd. and would propel the company’s Skylon space plane.

In April 2015, Reaction Engines announced that an AFRL study had concluded that SABRE is feasible. And AFRL is bullish on the technology ; the lab will reveal two-stage-to-orbit SABRE-based concepts either this September, at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics’ (AIAA) SPACE 2016 conference in Long Beach, California, or in March 2017, at the 21st AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies

; the lab will reveal two-stage-to-orbit SABRE-based concepts either this September, at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics’ (AIAA) SPACE 2016 conference in Long Beach, California, or in March 2017, at the 21st AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference in China, said AFRL Aerospace Systems Directorate Aerospace Engineer Barry Hellman. [The Skylon Space Plane in Pictures].

Conference in China, said AFRL Aerospace Systems Directorate Aerospace Engineer Barry Hellman. [The Skylon Space Plane in Pictures].

I hear this author; however, can it pass military basic training/ boot camp? Think not.

Back when Alphabet was known as Google, the company bought Boston Dynamics, makers of the amazingly advanced robot named Atlas. At the time, Google promised that Boston Dynamics would stop taking military contracts, as it often did. But here’s the open secret about Atlas: She can enlist in the US military anytime she wants.

Technology transfer is a two-way street. Traditionally we think of technology being transferred from the public to the private sector, with the internet as just one example. The US government invests in and develops all kinds of important technologies for war and espionage, and many of those technologies eventually make their way to American consumers in one way or another. When the government does so consciously with both military and civilian capabilities in mind, it’s called dual-use tech.

But just because a company might not actively pursue military contracts doesn’t mean that the US military can’t buy (and perhaps improve upon) technology being developed by private companies. The defense community sees this as more crucial than ever, as government spending on research and development has plummeted. About one-third of R&D was being done by private industry in the US after World War II, and two-thirds was done by the US government. Today it’s the inverse.

A new laser tag coming our way; however, this time when you’re tagged, you really are dead.

US officials tout the ‘unprecedented power’ of killing lasers to be released by 2023.

The US Army will deploy its first laser weapons by 2023, according to a recently released report.

Mary J. Miller, Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Technology, speaking before the House Armed Services Committee on Monday, stated that, “I believe we’re very close,” when asked about progress with directed-energy, or laser, weapons.

I see articles and reports like the following about military actually considering fully autonomous missals, drones with missals, etc. I have to ask myself what happened to the logical thinking.

A former Pentagon official is warning that autonomous weapons would likely be uncontrollable in real-world situations thanks to design failures, hacking, and external manipulation. The answer, he says, is to always keep humans “in the loop.”

The new report, titled “ Autonomous Weapons and Operational Risk,” was written by Paul Scharre, a director at the Center for a New American Security. Scharre used to work at the office of the Secretary of Defense where he helped the US military craft its policy on the use of unmanned and autonomous weapons. Once deployed, these future weapons would be capable of choosing and engaging targets of their own choosing, raising a host of legal, ethical, and moral questions. But as Scharre points out in the new report, “They also raise critically important considerations regarding safety and risk.”

As Scharre is careful to point out, there’s a difference between semi-autonomous and fully autonomous weapons. With semi-autonomous weapons, a human controller would stay “in the loop,” monitoring the activity of the weapon or weapons system. Should it begin to fail, the controller would just hit the kill switch. But with autonomous weapons, the damage that be could be inflicted before a human is capable of intervening is significantly greater. Scharre worries that these systems are prone to design failures, hacking, spoofing, and manipulation by the enemy.