Sir Winston Churchill often spoke of World War 2 as the “Wizard War”. Both the Allies and Axis powers were in a race to gain the electronic advantage over each other on the battlefield. Many technologies were born during this time – one of them being the ability to decipher coded messages. The devices that were able to achieve this feat were the precursors to the modern computer. In 1946, the US Military developed the ENIAC, or Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer. Using over 17,000 vacuum tubes, the ENIAC was a few orders of magnitude faster than all previous electro-mechanical computers. The part that excited many scientists, however, was that it was programmable. It was the notion of a programmable computer that would give rise to the  idea of artificial intelligence (AI).

idea of artificial intelligence (AI).

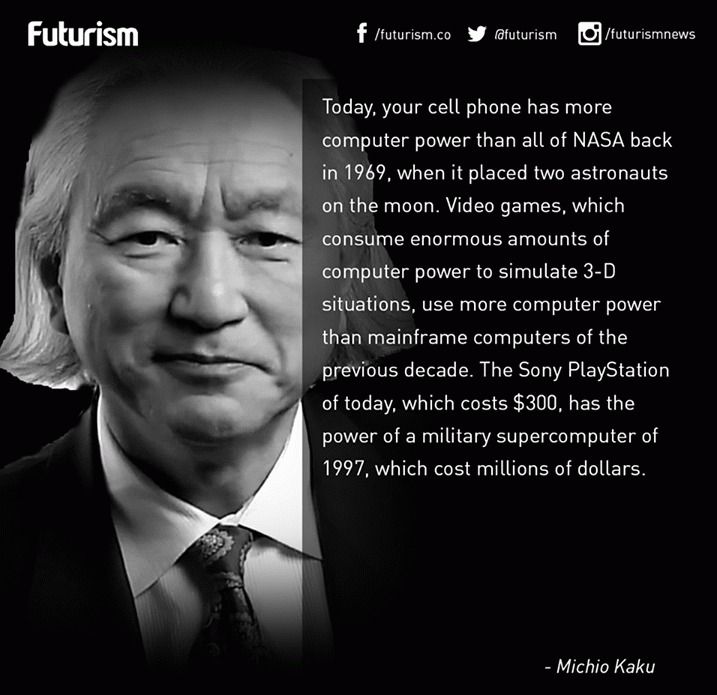

As time marched forward, computers became smaller and faster. The invention of the transistor semiconductor gave rise to the microprocessor, which accelerated the development of computer programming. AI began to pick up steam, and pundits began to make grand claims of how computer intelligence would soon surpass our own. Programs like ELIZA and Blocks World fascinated the public and certainly gave the perception that when computers became faster, as they surely would in the future, they would be able to think like humans do.

But it soon became clear that this would not be the case. While these and many other AI programs were good at what they did, neither they, or their algorithms were adaptable. They were ‘smart’ at their particular task, and could even be considered intelligent judging from their behavior, but they had no understanding of the task, and didn’t hold a candle to the intellectual capabilities of even a typical lab rat, let alone a human.

Read more