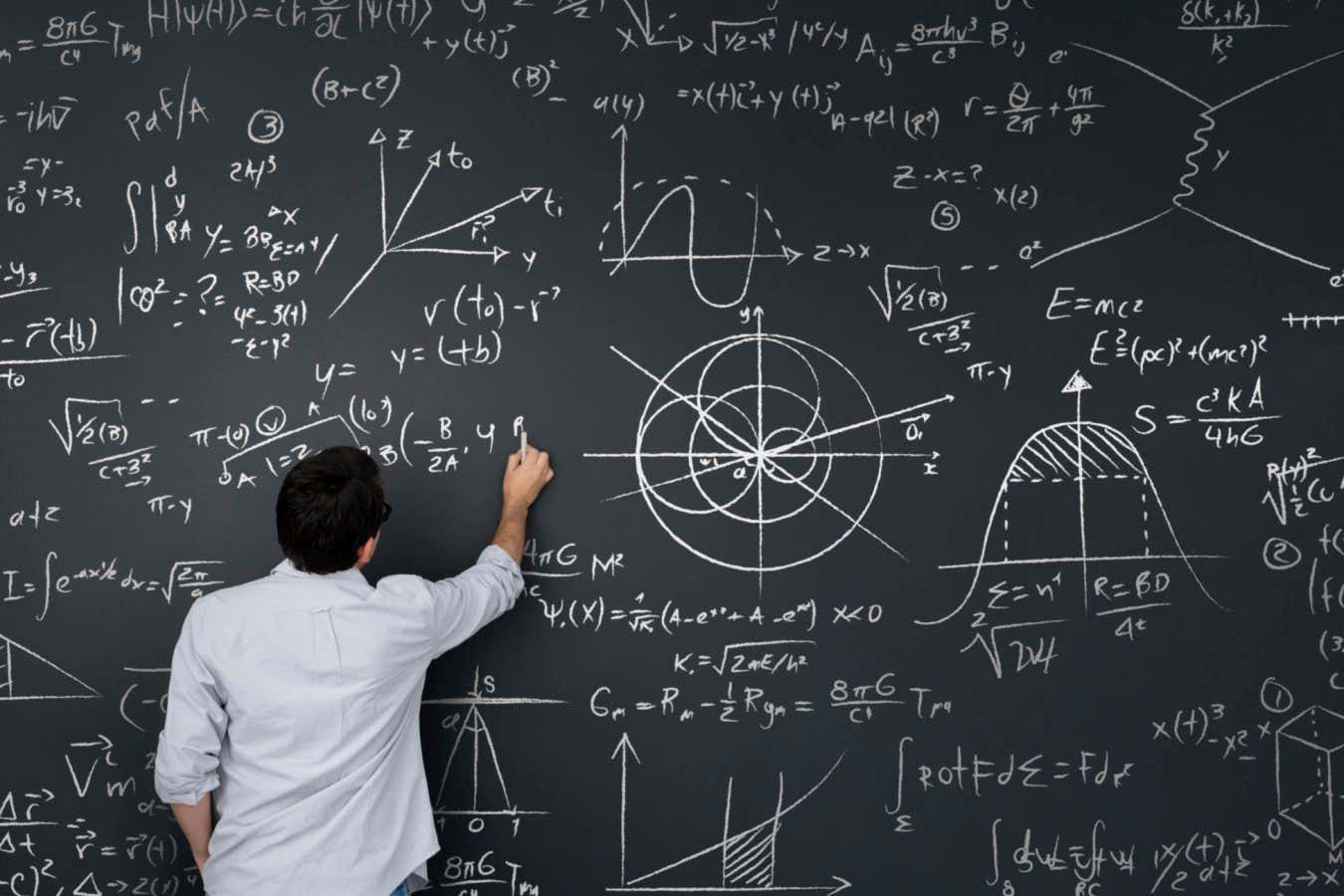

I’m back, baby. I’ve been away traveling for podcasts and am excited to bring you new ones with Michael Levin, William Hahn, Robin Hanson, and Emily Riehl, coming up shortly. They’re already recorded. I’ve been recovering from a terrible flu but pushed through it to bring you today’s episode with Urs Schreiber. This one is quite mind-blowing. It’s quite hairy mathematics, something called higher category theory, and how using this math (which examines the structure of structure) allows one manner of finding \.

Category: mathematics – Page 37

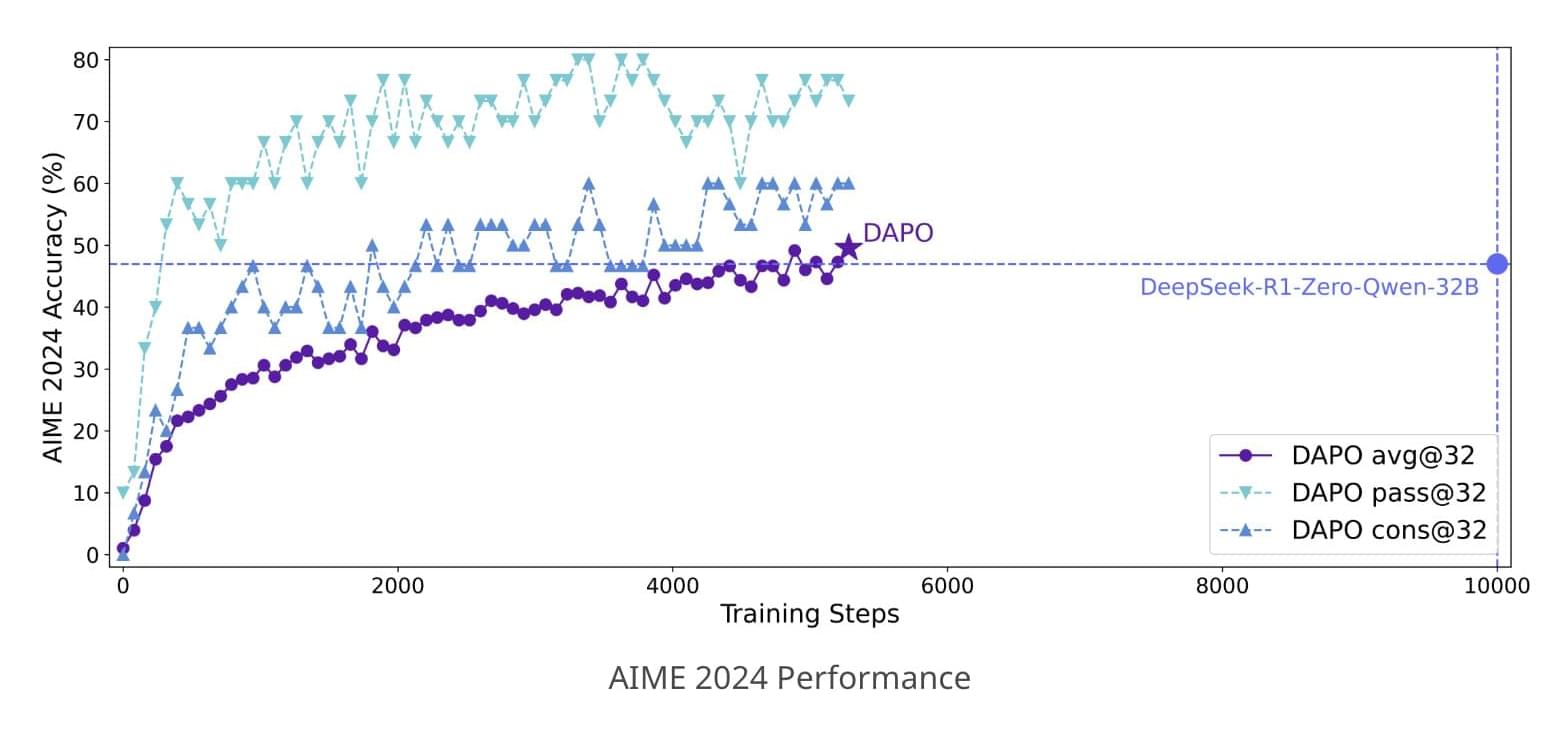

ByteDance Research Releases DAPO: A Fully Open-Sourced LLM Reinforcement Learning System at Scale

Reinforcement learning (RL) has become central to advancing Large Language Models (LLMs), empowering them with improved reasoning capabilities necessary for complex tasks. However, the research community faces considerable challenges in reproducing state-of-the-art RL techniques due to incomplete disclosure of key training details by major industry players. This opacity has limited the progress of broader scientific efforts and collaborative research.

Researchers from ByteDance, Tsinghua University, and the University of Hong Kong recently introduced DAPO (Dynamic Sampling Policy Optimization), an open-source large-scale reinforcement learning system designed for enhancing the reasoning abilities of Large Language Models. The DAPO system seeks to bridge the gap in reproducibility by openly sharing all algorithmic details, training procedures, and datasets. Built upon the verl framework, DAPO includes training codes and a thoroughly prepared dataset called DAPO-Math-17K, specifically designed for mathematical reasoning tasks.

DAPO’s technical foundation includes four core innovations aimed at resolving key challenges in reinforcement learning. The first, “Clip-Higher,” addresses the issue of entropy collapse, a situation where models prematurely settle into limited exploration patterns. By carefully managing the clipping ratio in policy updates, this technique encourages greater diversity in model outputs. “Dynamic Sampling” counters inefficiencies in training by dynamically filtering samples based on their usefulness, thus ensuring a more consistent gradient signal. The “Token-level Policy Gradient Loss” offers a refined loss calculation method, emphasizing token-level rather than sample-level adjustments to better accommodate varying lengths of reasoning sequences. Lastly, “Overlong Reward Shaping” introduces a controlled penalty for excessively long responses, gently guiding models toward concise and efficient reasoning.

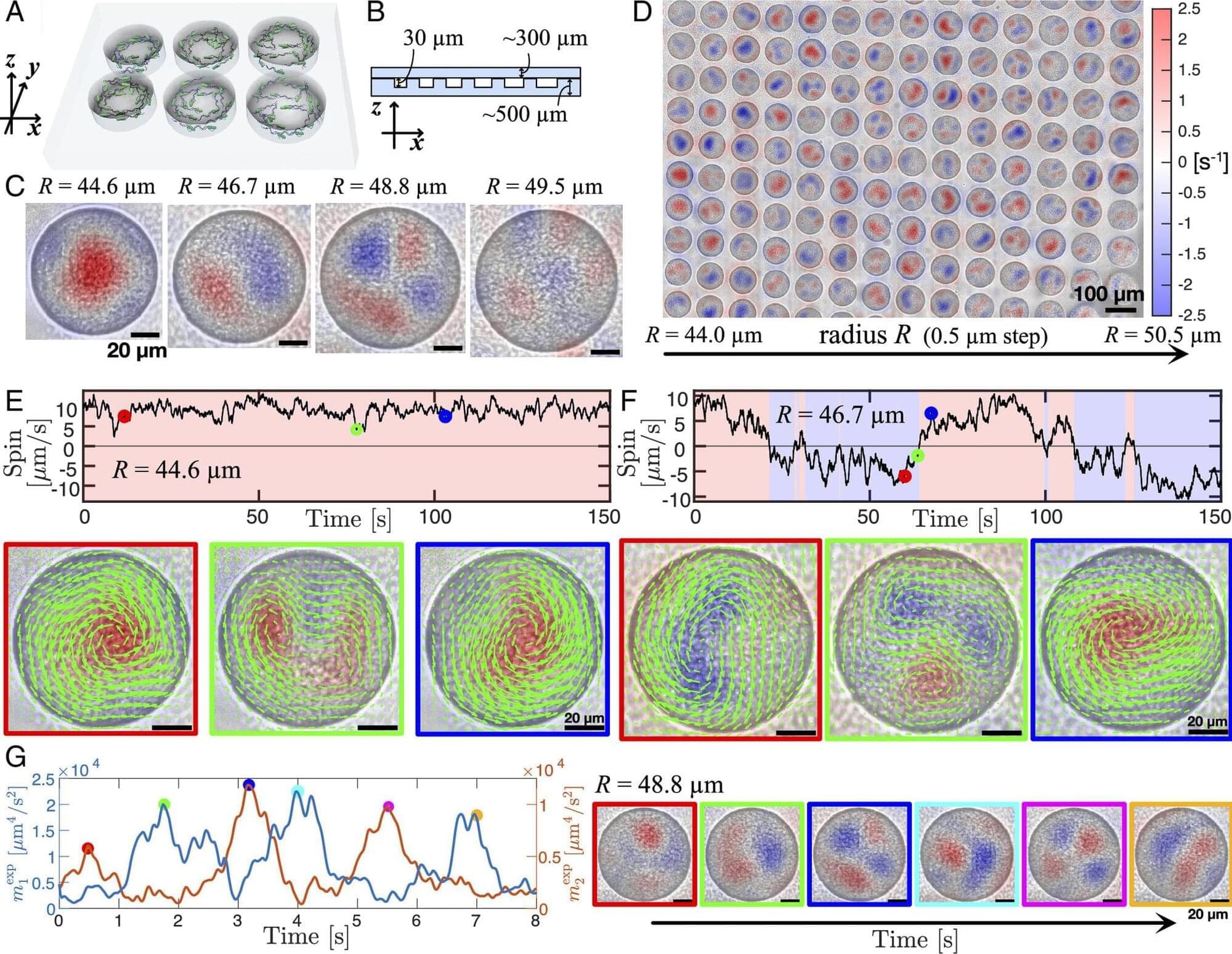

From order to chaos: Understanding the principles behind collective motion in bacteria

The collective motion of bacteria—from stable swirling patterns to chaotic turbulent flows—has intrigued scientists for decades. When a bacterial swarm is confined in small circular space, stable rotating vortices are formed. However, as the radius of this confined space increases, the organized swirling pattern breaks down into a turbulent state.

This transition from ordered to chaotic flow has remained a long-standing mystery. It represents a fundamental question not only in the study of bacterial behavior but also in classical fluid dynamics, where understanding the emergence of turbulence is crucial for both controlling and utilizing complex flows.

In a recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 14, 2025, a research team led by Associate Professor Daiki Nishiguchi from the Institute of Science Tokyo, Japan, has revealed in detail how bacterial swarms transition from organized movement to chaotic flow. Combining large-scale experiments, computer modeling, and mathematical analysis, the team observed and explained previously unknown intermediate states that emerge between order and turbulence.

James Fodor — Exploring the Frontiers of Computational Neuroscience

James Fodor discusses what he is researching, mind uploading etc.

As of 2020, James Fodor, is a student at the Australian National University, in Canberra, Australia. James’ studies at university have been rather diverse, and have at different times included history, politics, economics, philosophy, mathematics, computer science, physics, chemistry, and biology. Eventually he hopes to complete a PhD in the field of computational neuroscience.

James also have a deep interest in philosophy, history, and religion, which he periodically writes about on his blog, which is called The Godless Theist. In addition, James also has interests in and varying levels of involved in skeptical/atheist activism, effective altruism, and transhumanism/emerging technologies. James is a fan of most things sci-fi, including Star Trek, Dr Who, and authors such as Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov.

Many thanks for watching!

Consider supporting SciFuture by:

a) Subscribing to the SciFuture YouTube channel: http://youtube.com/subscription_center?add_user=TheRationalFuture b) Donating.

- Bitcoin: 1BxusYmpynJsH4i8681aBuw9ZTxbKoUi22

- Ethereum: 0xd46a6e88c4fe179d04464caf42626d0c9cab1c6b.

- Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/scifuture c) Sharing the media SciFuture creates: http://scifuture.org.

Kind regards.

This Brain Organoid Shockingly Outperforms Our AI!

In this video, Dr. Ardavan (Ahmad) Borzou will discuss a rising technology in constructing bio-computers for AI tasks, namely Brainoware, which is made of brain organoids interfaced by electronic arrays.

Need help for your data science or math modeling project?

https://compu-flair.com/solution/

🚀 Join the CompuFlair Community! 🚀

📈 Sign up on our website to access exclusive Data Science Roadmap pages — a step-by-step guide to mastering the essential skills for a successful career.

💪As a member, you’ll receive emails on expert-engineered ChatGPT prompts to boost your data science tasks, be notified of our private problem-solving sessions, and get early access to news and updates.

👉 https://compu-flair.com/user/register.

Comprehensive Python Checklist (machine learning and more advanced libraries will be covered on a different page):

https://compu-flair.com/blogs/program… — Introduction 02:16 — Von Neumann Bottleneck 03:54 — What is brain organoid 05:09 — Brainoware: reservoir computing for AI 06:29 — Computing properties of Brainoware: Nonlinearity & Short-Memory 09:27 — Speech recognition by Brainoware 12:25 — Predicting chaotic motion by Brainoware 13:39 — Summary of Brainoware research 14:35 — Can brain organoids surpass the human brain? 15:51 — Will humans evolve to a body-less stage in their evolution? 16:30 — What is the mathematical model of Brainoware?

00:00 — Introduction.

02:16 — Von Neumann Bottleneck.

03:54 — What is brain organoid.

05:09 — Brainoware: reservoir computing for AI

06:29 — Computing properties of Brainoware: Nonlinearity & Short-Memory.

09:27 — Speech recognition by Brainoware.

12:25 — Predicting chaotic motion by Brainoware.

13:39 — Summary of Brainoware research.

14:35 — Can brain organoids surpass the human brain?

15:51 — Will humans evolve to a body-less stage in their evolution?

16:30 — What is the mathematical model of Brainoware?

D-Wave claims its quantum computers can solve a problem of scientific relevance much faster than classical methods

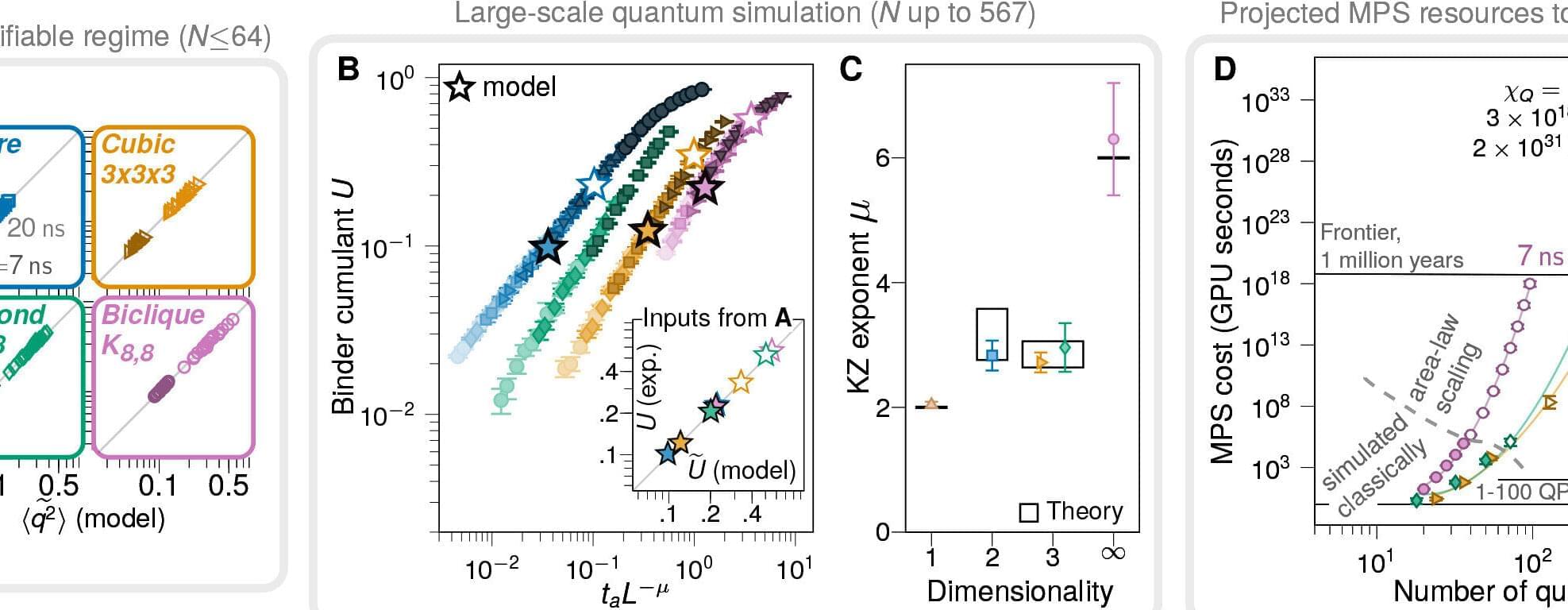

A team of quantum computer researchers at quantum computer maker D-Wave, working with an international team of physicists and engineers, is claiming that its latest quantum processor has been used to run a quantum simulation faster than could be done with a classical computer.

In their paper published in the journal Science, the group describes how they ran a quantum version of a mathematical approximation regarding how matter behaves when it changes states, such as from a gas to a liquid—in a way that they claim would be nearly impossible to conduct on a traditional computer.

Over the past several years, D-Wave has been working on developing quantum annealers, which are a subtype of quantum computer created to solve very specific types of problems. Notably, landmark claims made by researchers at the company have at times been met with skepticism by others in the field.

Model uses quantum mechanics to show how the brain makes decisions more quickly than computers in risky situations

In research inspired by the principles of quantum mechanics, researchers from Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) and the University of Oxford reveal new findings to understand why the human brain is able to make decisions quicker than the world’s most powerful computer in the face of a critical risk situation. The human brain has this capacity despite the fact that neurons are much slower at transmitting information than microchips, which raises numerous unknown factors in the field of neuroscience.

The research is published in the journal Physical Review E.

It should be borne in mind that in many other circumstances, the human brain is not quicker than technological devices. For example, a computer or calculator can resolve mathematical operations far faster than a person. So, why is it that in critical situations—for example, when having to make an urgent decision at the wheel of a car—the human brain can surpass machines?

Quantum entanglement wins: Researchers report quantum advantage in a simple cooperation game

Quantum systems hold the promise of tackling some complex problems faster and more efficiently than classical computers. Despite their potential, so far only a limited number of studies have conclusively demonstrated that quantum computers can outperform classical computers on specific tasks. Most of these studies focused on tasks that involve advanced computations, simulations or optimization, which can be difficult for non-experts to grasp.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the University of Sevilla recently demonstrated a quantum advantage over a classical scenario on a cooperation task called the odd-cycle game. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, shows that a team with quantum entanglement can win this game more often than a team without.

“There is a lot of talk about quantum advantage and how quantum systems will revolutionize entire industries, but if you look closely, in many cases, there is no mathematical proof that classical methods definitely cannot find solutions as efficiently as quantum algorithms,” Peter Drmota, first author of the paper, told Phys.org.