Category: life extension – Page 618

Why Are These People Eating Pills of Poop? (Medical Fecal Transplants)

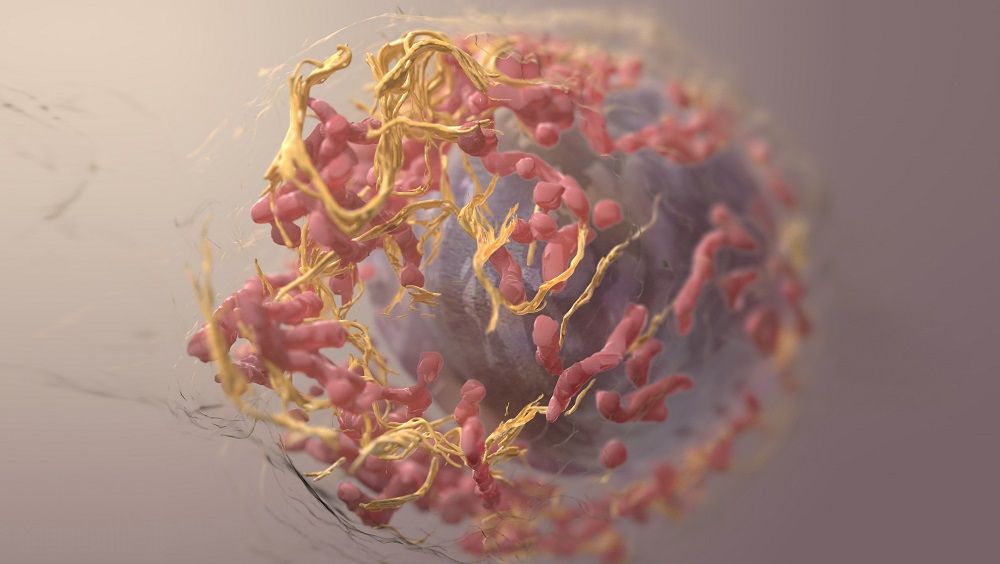

The straight poop on fecal transplants. Scientists think fecal transplants help us live longer, healthier lives.

Quote: “Seres Therapeutics is one of the more promising names in poop.”

Here’s the straight poop on fecal transplants, a new medical procedure which physicians use to treat infections. Geroscientists suspect that fecal transplants could help us live longer, healthier lives by giving us a microbiome upgrade. [This report was originally published on LongevityFacts.com. Author: Brady Hartman]

The human microbiome is an invisible world that is only recently coming into focus. The collection of bacteria that inhabit your body is a delicate ecosystem that can crash as you age, travel, or even take a new medication. When it collapses, it can lead to all sorts of distress.

The Business End Of The Poop Industry

Seres Therapeutics is one of the more promising names in poop. The Cambridge biotech company has been trying to transform medicine by harnessing the billions of bacteria in our intestines.

Preventing Type 2 Diabetes

Summary: People can delay or prevent type 2 diabetes with a healthy diet and exercise. Medications also work but are less effective than lifestyle changes. [This article first appeared on the LongevityFacts.com website. Author: Brady Hartman.]

According to the CDC, the ways to delay or prevent type 2 diabetes include diet, exercise, and in some cases, medications. Don’t take risks with your health – all three of these tactics should only be carried out under the supervision of a qualified physician.

Research shows that some prevention strategies are more successful than others in preventing type 2 diabetes.

Hunting Breakthrough Cures for Dementia (Best of 2017 Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Reports)

Summary: A wrap-up of the 2017 reports on the search for breakthrough treatments for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, and other forms of dementia, showing the advancements made in understanding, treating and preventing these neurodegenerative diseases, including promising therapies in the pipeline. [This article first appeared on the website LongevityFacts.com. Author: Brady Hartman. ]

During 2017, researchers made advances towards understanding what causes Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other forms of dementia. During the year, brain scientists announced they have many promising treatments for dementia in the pipeline. Moreover, researchers have suggested ways to prevent these disabling neurodegenerative diseases.

Here’s a wrap-up of advancements made in understanding, treating and preventing dementia.

Coffee Improves Brain Health, Prevents Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Say Researchers

Summary: Researchers say coffee prevents Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s for those consuming 3 cups daily. The brain health benefits of the beverage seem to differ between decaf and regular coffee. [Author: Brady Hartman. This article first appeared on LongevityFacts.com.]

Perhaps you’ve heard the latest news – the evidence on coffee’s health benefits is increasing every day.

In fact, new research shows that coffee protects your brain, and recent studies show that daily coffee drinkers have a significantly reduced risk of both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

New Breakthrough Drug Canakinumab Slashes Heart Attack and Cancer in Clinical Trial

In last years CANTOS trial, the anti-inflammatory drug Canakinumab reduced heart attacks 25% and cancer by 50%.

(Part of the look back at the best of 2017)

Summary: The drug Canakinumab reduced heart attacks by 25% and cancer by 50% by reducing chronic inflammation, according to the authors of the recent CANTOS trial. [This report was originally published on LongevityFacts on Aug 27, 2017, and has been updated. Author: Brady Hartman]

In late August, researchers announced that they had found a breakthrough drug which reduces heart attack risk by one-fourth while cutting the risk of cancer in half. The researchers announced that the new medicine can prevent tens of thousands of deaths from heart attack and cancer.

Biggest Breakthrough Since Statins

Harvard researchers said the discovery promises to “usher in a new era” of treatment. Presenting their findings at one of the largest gatherings of heart experts, doctors hail the new drug as the “biggest breakthrough since statins.”

New RNA Telomere Therapy Reverses Aging

(Part of the look back at the best of 2017)

Summary: Doctors lengthen telomeres with RNA therapy to reverse aging in human cells, according to a new research report. Telomere attrition is one of the nine hallmarks of aging. [Author: Brady Hartman] This article first appeared on LongevityFacts.]

Dr. John Cooke is department chair of cardiovascular sciences at Houston Methodist Research Institute and is the lead author of a recent paper published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Dr. Cooke’s team used RNA therapy to lengthen the telomeres of patients’ cells, making them younger in the process. In a video statement accompanying the report, the lead author remarked:

“We can make aged cells younger.”

Fifty years frozen: The world’s first cryonically preserved human’s disturbing journey to immortality

“Yes, Mr. Bedford is here.”

That’s what Marji Klima, executive assistant at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, told me over email this week. She was referring to Dr. James Hiram Bedford, a former University of California-Berkeley psychology professor who died of renal cancer on Jan. 12, 1967. Bedford was the first human to be cryonically preserved—that is, frozen and stored indefinitely in the hopes that technology to revive him will one day exist. He’s been at Alcor since 1991.

His was the first of 300 bodies and brains currently preserved in the world’s three known commercial cryonics facilities: Alcor; the Cryonics Institute in Clinton Township, Michigan; and KrioRus near Moscow. Another 3,000 people still living have arranged to join them upon what cryonicists call “deanimation.” In other words, death.