If you’ve ever watched a glass blower at work, you’ve seen a material behaving in a very special way. As it cools, the viscosity of molten glass increases steadily but gradually, allowing it to be shaped without a mold. Physicists call this behavior a strong glass transition, and silica glass is the textbook example. Most polymer glasses behave very differently, and are known as fragile glass formers. Their viscosity rises much more steeply as temperature drops, and therefore they cannot be processed without a mold or very precise temperature control.

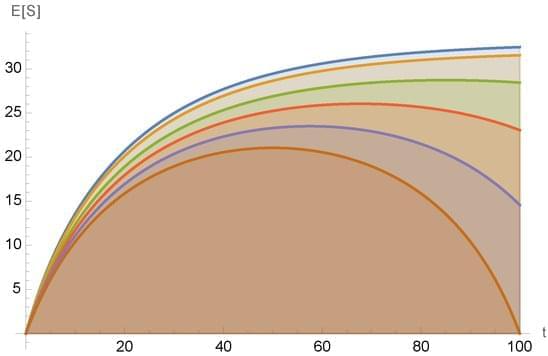

There are other interesting differences between different glass formers. Most glasses exhibit relaxation behavior that deviates strongly from a single-exponential decay; this means that their relaxation is characterized by a broad spectrum of relaxation times, and is often associated with dynamic heterogeneities or cooperative rearrangements.

A long-standing empirical rule links the breadth of the relaxation spectrum to the fragility of the glass: strong glass formers such as silica tend to have a narrow relaxation spectrum, while fragile glass formers such as polymers have a much broader relaxation spectrum.