Algorithm set for deployment in Japan could identify giant temblors faster and more reliably.

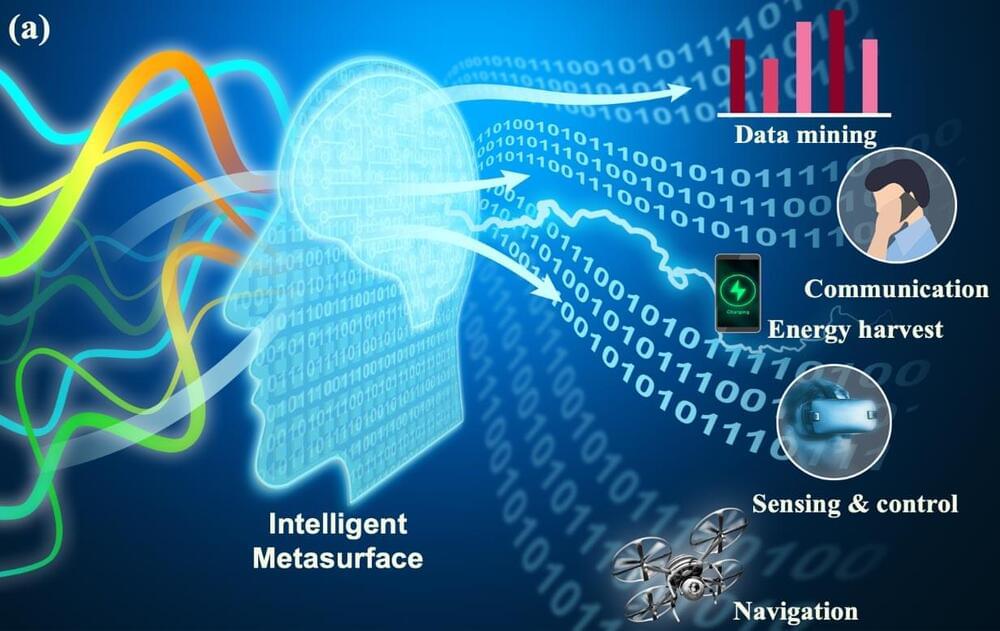

Two minutes after the world’s biggest tectonic plate shuddered off the coast of Japan, the country’s meteorological agency issued its final warning to about 50 million residents: A magnitude 8.1 earthquake had generated a tsunami that was headed for shore. But it wasn’t until hours after the waves arrived that experts gauged the true size of the 11 March 2011 Tohoku quake. Ultimately, it rang in at a magnitude 9—releasing more than 22 times the energy experts predicted and leaving at least 18,000 dead, some in areas that never received the alert. Now, scientists have found a way to get more accurate size estimates faster, by using computer algorithms to identify the wake from gravitational waves that shoot from the fault at the speed of light.

“This is a completely new [way to recognize] large-magnitude earthquakes,” says Richard Allen, a seismologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. “If we were to implement this algorithm, we’d have that much more confidence that this is a really big earthquake, and we could push that alert out over a much larger area sooner.”

Scientists typically detect earthquakes by monitoring ground vibrations, or seismic waves, with devices called seismometers. The amount of advance warning they can provide depends on distance between the earthquake and the seismometers, and the speed of the seismic waves, which travel less than 6 kilometers per second. Networks in Japan, Mexico, and California provide seconds or even minutes of advance warning, and the approach works well for relatively small temblors. But beyond magnitude 7, the earthquake waves can saturate seismometers. This makes the most destructive earthquakes, like Japan’s Tohoku quake, the most challenging to identify, Allen says.