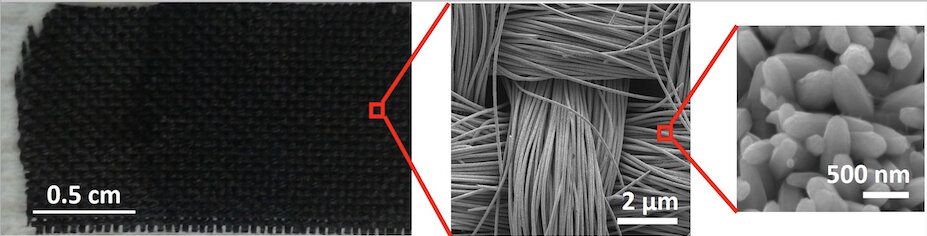

In an effort to make highly sensitive sensors to measure sugar and other vital signs of human health, Iowa State University’s Sonal Padalkar figured out how to deposit nanomaterials on cloth and paper.

Feedback from a peer-reviewed paper published by ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering describing her new fabrication technology mentioned the metal-oxide nanomaterials the assistant professor of mechanical engineering was working with—including zinc oxide, cerium oxide and copper oxide, all at scales down to billionths of a meter—also have antimicrobial properties.

“I might as well see if I can do something else with this technology,” Padalkar said. “And that’s how I started studying antimicrobial uses.”