#Hackers are seeking to exploit the roll-out of government financial relief plans to fill their own pockets at the expense of businesses and affected workers, Israeli cyber researchers have revealed.

Hackers are exploiting the rollout of governmental financial relief to fill their pockets at the expense of businesses and affected workers, according to Israeli cyber researchers.

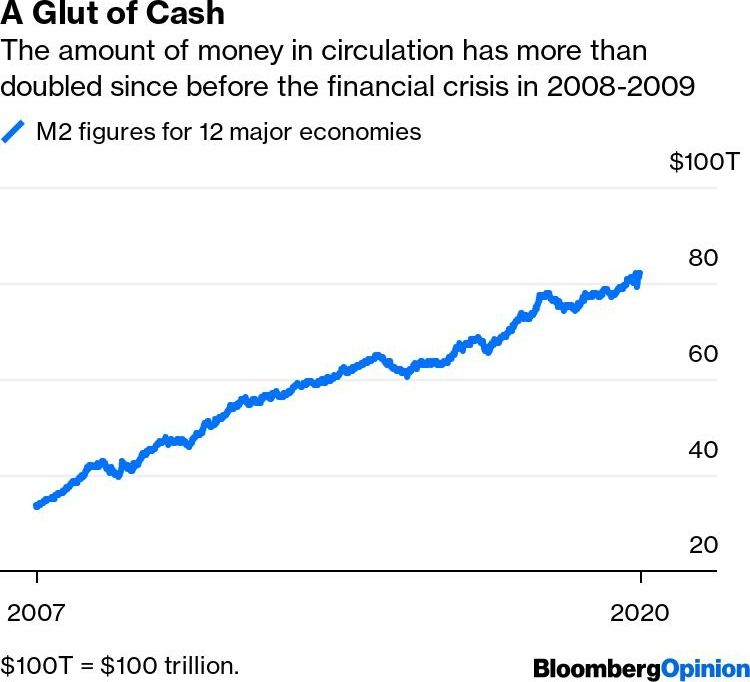

In recent weeks, governments have sought to ease cash-flow shortages and avoid a recession with ambitious stimulus packages and grants to households, including a massive $2 trillion economic package in the United States.

According to researchers at Israeli cybersecurity giant Check Point, a major increase in malicious and suspicious domains related to relief packages has been registered in recent weeks. The hackers aim to scam individuals into providing personal information, thereby stealing money or committing fraud.

“To do this, they are evolving the scam and phishing techniques that they have been using successfully since the start of the pandemic in January,” the researchers wrote in a recent report.