But the practical challenges of breeding and maintaining unconventional lab animals persist.

Researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory have created the largest simulation to date of an entire gene of DNA, a feat that required one billion atoms to model and will help researchers to better understand and develop cures for diseases like cancer.

“It is important to understand DNA at this level of detail because we want to understand precisely how genes turn on and off,” said Karissa Sanbonmatsu, a structural biologist at Los Alamos. “Knowing how this happens could unlock the secrets to how many diseases occur.”

Modeling genes at the atomistic level is the first step toward creating a complete explanation of how DNA expands and contracts, which controls genetic on/off switching.

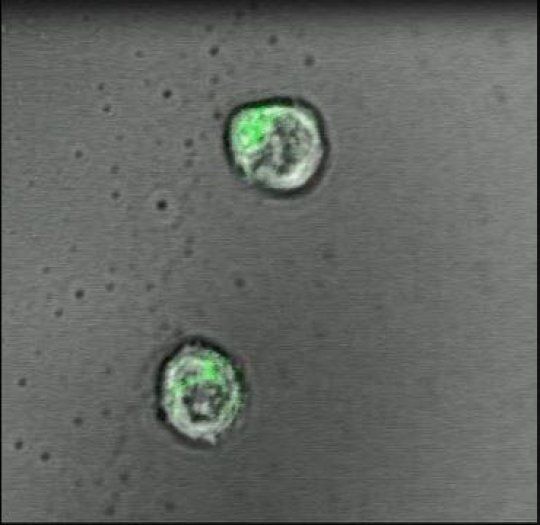

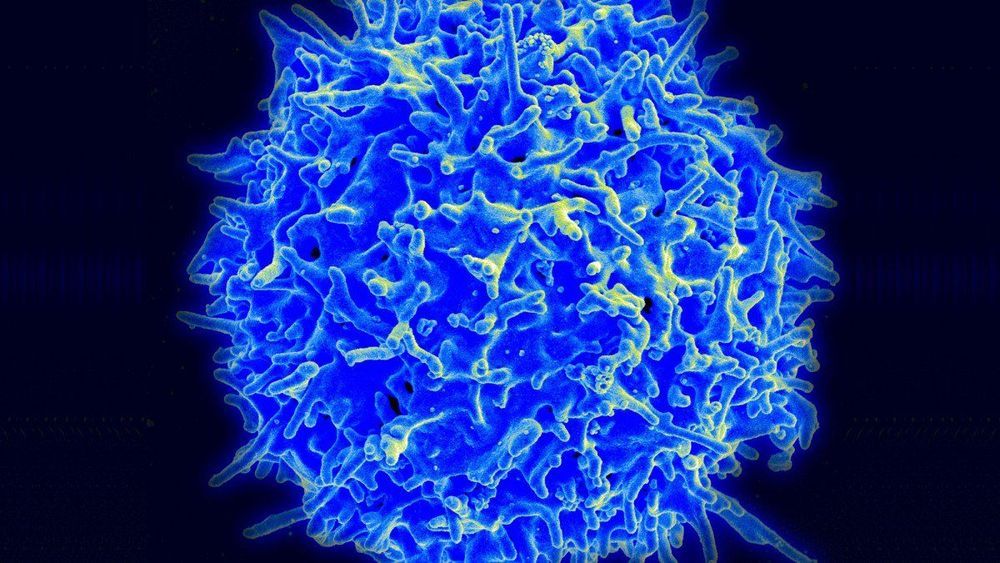

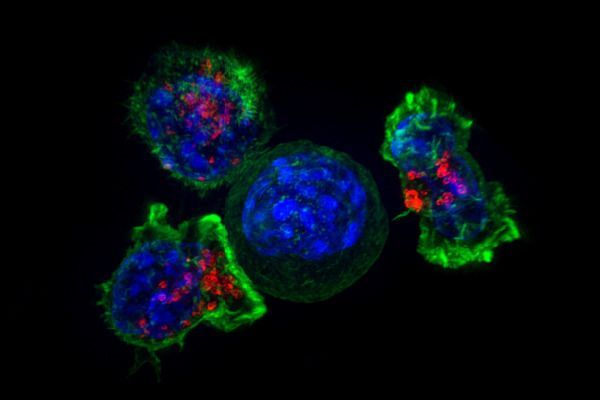

In a proof-of-principle study in mice, scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine report the creation of a specialized gel that acts like a lymph node to successfully activate and multiply cancer-fighting immune system T-cells. The work puts scientists a step closer, they say, to injecting such artificial lymph nodes into people and sparking T-cells to fight disease.

In the past few years, a wave of discoveries has advanced new techniques to use T-cells – a type of white blood cell – in cancer treatment. To be successful, the cells must be primed, or taught, to spot and react to molecular flags that dot the surfaces of cancer cells. The job of educating T-cells this way typically happens in lymph nodes, small, bean-shaped glands found all over the body that house T-cells. But in patients with cancer and immune system disorders, that learning process is faulty, or doesn’t happen.

To address such defects, current T-cell booster therapy requires physicians to remove T-cells from the blood of a patient with cancer and inject the cells back into the patient after either genetically engineering or activating the cells in a laboratory so they recognize cancer-linked molecular flags.

Circulation and cellular activity were restored in a pig’s brain four hours after its death, a finding that challenges long-held assumptions about the timing and irreversible nature of the cessation of some brain functions after death, Yale scientists report April 18 in the journal Nature.

The brain of a postmortem pig obtained from a meatpacking plant was isolated and circulated with a specially designed chemical solution. Many basic cellular functions, once thought to cease seconds or minutes after oxygen and blood flow cease, were observed, the scientists report.

“The intact brain of a large mammal retains a previously underappreciated capacity for restoration of circulation and certain molecular and cellular activities multiple hours after circulatory arrest,” said senior author Nenad Sestan, professor of neuroscience, comparative medicine, genetics, and psychiatry.

The gene-editing tool has been used in a trial to enhance the blood cells of two patients with cancer.

The trial: The experimental research, under way at the University of Pennsylvania, involves genetically altering a person’s T cells so that they attack and destroy cancer. A university spokesman confirmed it has treated the first patients, one with sarcoma and one with multiple myeloma.

Slow start: Plans for the pioneering study were first reported in 2016, but it was slow to get started. Chinese hospitals, meanwhile, have launched a score of similar efforts. Carl June, the famed University of Pennsylvania cancer doctor, has compared the Chinese lead in employing CRISPR to a genetic Sputnik.

Oral cancer is known for its high mortality rate in developing countries, but an international team of scientists hope its latest discovery will change that.

Researchers from the University of Otago and the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), Kolkata, have discovered epigenetic markers that are distinctly different in oral cancer tissues compared to the adjacent healthy tissues in patients.

Co-author Dr. Aniruddha Chatterjee, of Otago’s Department of Pathology, says finding these biomarkers is strongly associated with patient survival.

Researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) have discovered that gene mutations that once helped humans survive may increase the possibility for diseases, including cancer.

The findings were recently the cover story in the journal Genome Research.

The team of researchers from BGU’s National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev (NIBN) set out to look for mutations in the genome of the mitochondria, a part of every cell responsible for energy production that is passed exclusively from mothers to their children. The mitochondria are essential to every cell’s survival and our ability to perform the functions of living.