Recently, we had the opportunity to interview Professor George Church, a well-known geneticist and rejuvenation expert whom we have previously interviewed. Prof. Church’s company, Rejuvenate Bio, will be launching a clinical trial to test a rejuvenation therapy in dogs this fall.

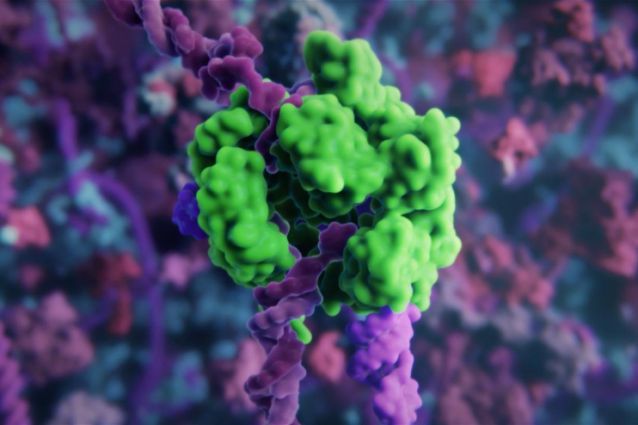

In your recent paper on enabling large-scale genome editing, you talked about manipulating endogenous transposable elements with the help of dead Cas9 base editors. At Ending Age-Related Diseases, Andrei Gudkov spoke about the super mutagenic phenotype that arises from the expression of LINE1 reverse transcriptase. In this context, he mentioned the possibility of the retrobiome (as he referred to it) being the main driver of all types of cellular damage, which is consequently improperly addressed due to immunosenescence. Do you share his views on the contribution of LINEs and SINEs in aging? If not, why?

Yes. That is one of the reasons why we explored the tech for editing of repeats. We are now extending this to the germline engineering of repeats.