Scientists like Prof Sinclair have evidence of speeding up, slowing, and even reversing aging.

Thanks to LastPass for sponsoring this video. Click here to start using LastPass: https://ve42.co/VeLP

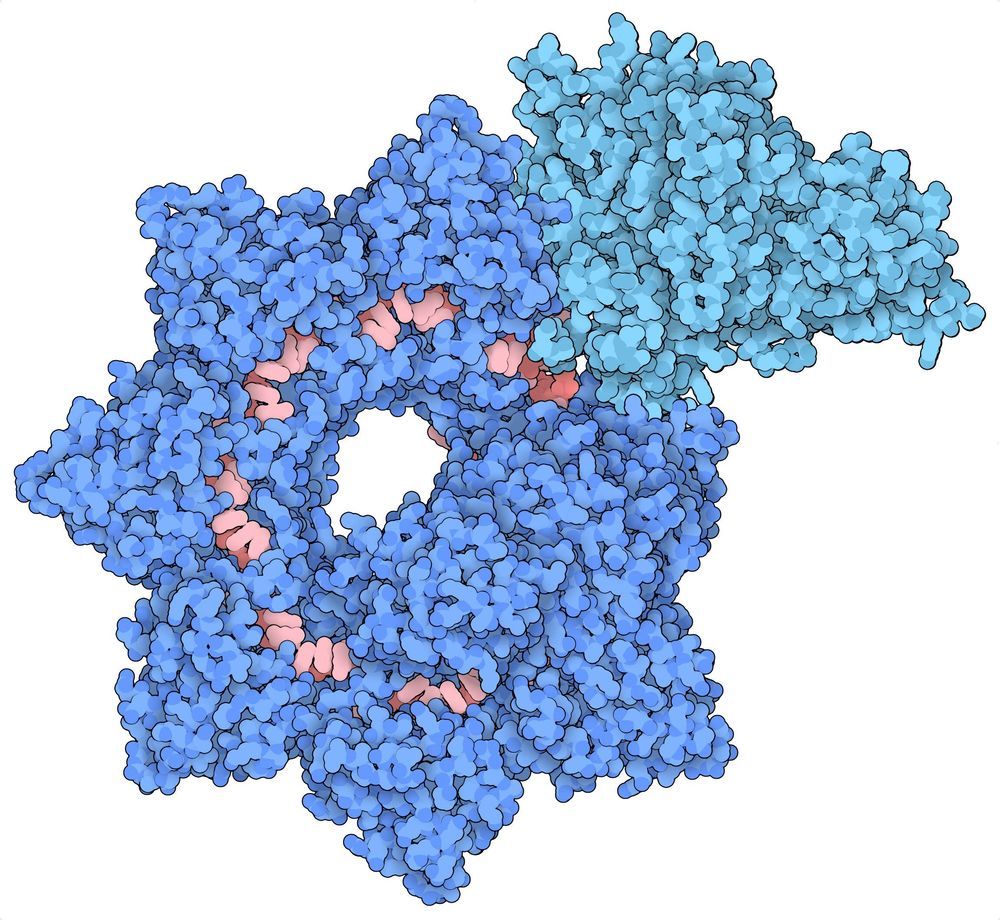

What causes aging? According to Professor David Sinclair, it is a loss of information in our epigenome, the system of proteins like histones and chemical markers like methylation that turn on and off genes. Epigenetics allow different cell types to perform their specific functions — they are what differentiate a brain cell from a skin cell. Our DNA is constantly getting broken, by cosmic rays, UV radiation, free radicals, x-rays and regular cell division etc. When our cells repair that damage, the epigenome is not perfectly reset. And hence over time, noise accumulates in our epigenome. Our cells no longer perform their functions well.

To counter this decline, we can activate the body’s own defenses against aging by stressing the body. Eat less, eat less protein, engage in intense exercise, experience uncomfortable cold. When the body senses existential threats it triggers longevity genes, which attempt to maintain the body to ensure its survival until good times return. This may be the evolutionary legacy of early bacteria, which established these two modes of living (repair and protect vs grow and reproduce). Scientists are uncovering ways to mimic stresses on the body without the discomfort of fasting. Molecules like NMN also trigger sirtuins to monitor and repair the epigenome. This may slow aging.

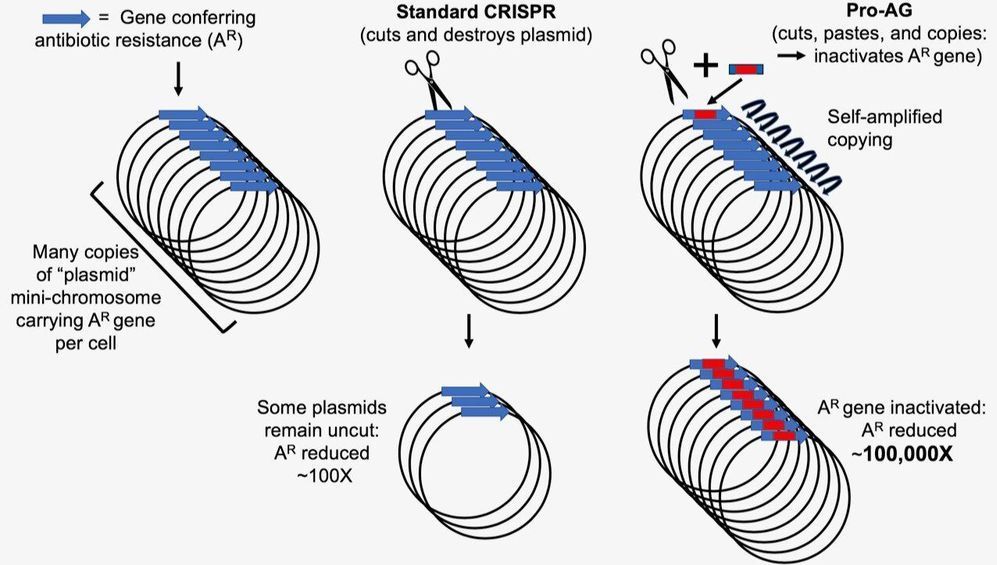

Reversing aging requires an epigenetic reset, which may be possible using Yamanaka factors. These four factors can revert an adult cell into a pluripotent stem cell. Prof. Sinclair used three of the four factors to reverse aging in the retinal cells of old mice. He found they could see again after the treatment.

Special thanks to:

Professor David Sinclair, check out his book “Lifespan: Why We Age & Why We Don’t Have To“

Assistant Professor David Gold

Noemie Sierra (for polyp images)

Genepool Productions for telomere animations from Immortal: https://ve42.co/immortal

Epigenetics animations (DNA, histones, methylation etc) courtesy of: http://wehi.tv

Animation: Etsuko Uno

Art and Technical Direction: Drew Berry

Sound Design: Francois Tetaz & Emma Bortignon

Scientific Consultation: Marnie Blewitt

Courtesy of Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

Filming, editing and animation by Jonny Hyman and Derek Muller.