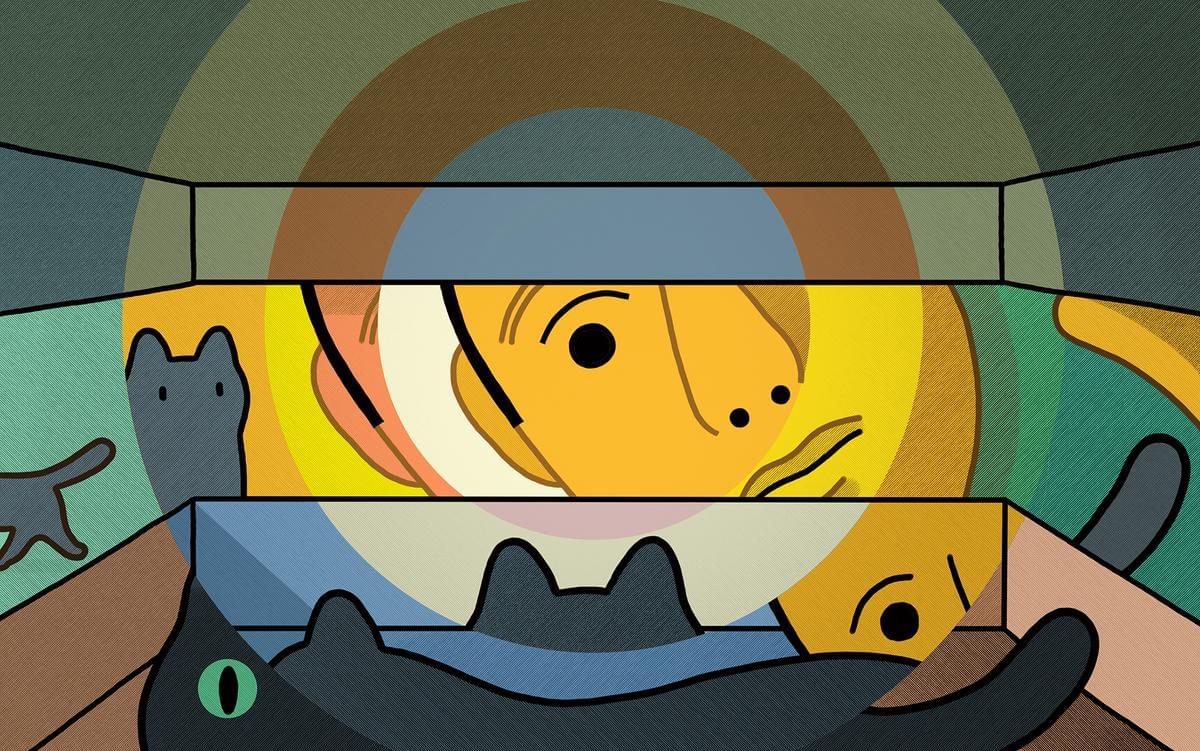

In recent years, a substantial number of established journals have received buyout offers from obscure entities, with some journals being acquired. Despite mounting circumstantial evidence of irregular behaviour exhibited by these journals post-acquisition, comprehensive analyses on this matter are lacking. To address this gap, this article examines the practices of Oxbridge Publishing House Ltd., a company registered in the UK in 2022. Through an analysis of publicly available documentation, it becomes apparent that this entity is part of a complex network of recently established companies. Since 2020 this network has acquired, with the help of intermediary firms, at least 36 scholarly journals originally published in countries such as Spain , United Kingdom , USA , India , Turkey , among others. Targeting journals indexed in prestigious scientific databases like Web of Science and Scopus, many of these journals see significant transformations upon acquisition, such as the introduction or substantial escalation of publication fees, often coupled with increases in publication volumes. This increase stems from a surge in contributions originating outside the journal’s original academic community. Their disregard for proper publishing standards is evident in their widespread use of fake DOIs or the appropriation of DOIs from unrelated documents. Drawing parallels to the film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, we refer to journals caught in this predicament as pod journals. This type of predatory publishing practice not only contributes to over-publication but also disenfranchises legitimate academic communities and poses a threat to academic bibliodiversity.