Pharma giant Novartis is developing drugs that could prevent cancer before patients get it. One big question: how will we pay for them?

What if woolly mammoths could walk the planet once again? De-extinction – or the process of creating an organism which is a member of, or closely resembles, an extinct species – was once a sci-fi fantasy only imaginable in films like “Jurassic Park.” But recent biological and technological breakthroughs indicate that reviving extinct creatures could become a reality. Even if advancements get us there, should we do it?

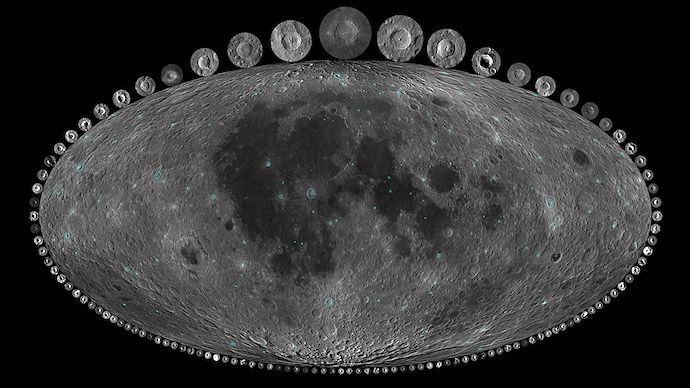

Dinosaurs never stood a chance once asteroid impacts more than doubled some 290 million years ago.

By studying the Moon, an international team of scientists revealed that the number of asteroids crashing into Earth and its satellite increased by two to three times toward the end of the Paleozoic era.

Contrary to popular belief, most of the planet’s more primitive asteroid-produced craters were not erased by erosion and other geologic processes.

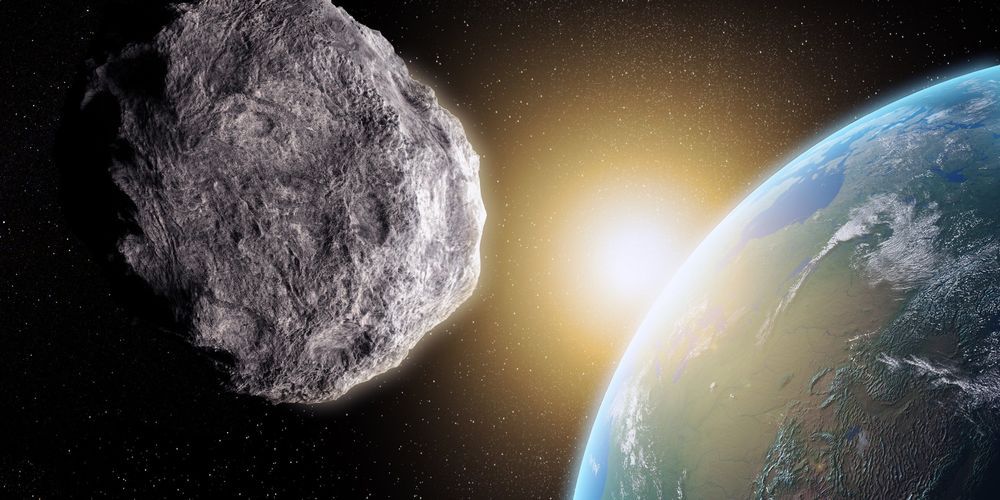

If an asteroid were to head towards Earth, we would be quite defenceless as we have not successfully developed a method that could reduce the impact of — or entirely avert — a devastating collision.

However, that may be about to change. NASA has approved a project called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), the aim of which is to throw a “small” asteroid off course in October 2022.

Saying farewell to coffee isn’t that easy. According to research about three-fifths of all our beloved coffee species are going to go extinct. This is a phenomenal amount of coffee that we risk losing.

Here’s something to think about as you sip that morning mochaccino:?Deforestation, climate change and the proliferation of pests and fungal pathogens are putting most of the world’s wild coffee species at risk of extinction.

At least 60 percent of wild coffee species are considered “threatened,” according to a study published this week in Science Advances. And fewer than half of all the wild species are safeguarded in so-called germplasm collections—banks for seed and living plants kept in protected areas as backups.

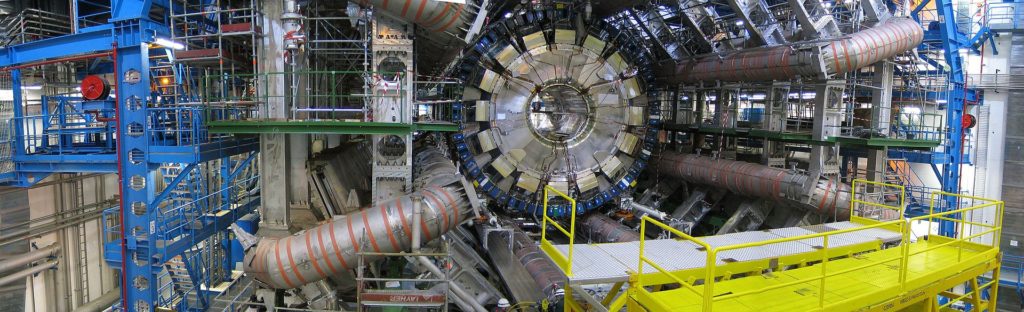

CERN has revealed plans for a gigantic successor of the giant atom smasher LHC, the biggest machine ever built. Particle physicists will never stop to ask for ever larger big bang machines. But where are the limits for the ordinary society concerning costs and existential risks?

CERN boffins are already conducting a mega experiment at the LHC, a 27km circular particle collider, at the cost of several billion Euros to study conditions of matter as it existed fractions of a second after the big bang and to find the smallest particle possible – but the question is how could they ever know? Now, they pretend to be a little bit upset because they could not find any particles beyond the standard model, which means something they would not expect. To achieve that, particle physicists would like to build an even larger “Future Circular Collider” (FCC) near Geneva, where CERN enjoys extraterritorial status, with a ring of 100km – for about 24 billion Euros.

Experts point out that this research could be as limitless as the universe itself. The UK’s former Chief Scientific Advisor, Prof Sir David King told BBC: “We have to draw a line somewhere otherwise we end up with a collider that is so large that it goes around the equator. And if it doesn’t end there perhaps there will be a request for one that goes to the Moon and back.”

“There

This was the first part in an interview series with Scott Aaronson — this one is on quantum computing — other segments are on Existential Risk, consciousness (including Scott’s thoughts on IIT) and thoughts on whether the universe is discrete or continuous.

First part in an interview series with Scott Aaronson — this one is on quantum computing — future segments will be on Existential Risk, consciousness (including Scott’s thoughts on IIT) and thoughts on whether the universe is discrete or continuous.

See ‘Complexity-Theoretic Foundations of Quantum Supremacy Experiments’

https://www.scottaaronson.com/papers/quantumsupre.pdf

Bio : Scott Aaronson is a theoretical computer scientist and David J. Bruton Jr. Centennial Professor of Computer Science at the University of Texas at Austin. His primary areas of research are quantum computing and computational complexity theory.

He blogs at Shtetl-Optimized: https://www.scottaaronson.com/blog/

Ok, the new version of my global risk prevention map is up (pdf link is in comments) and now it is accompanied by recently the published article “Approaches to the Prevention of Global Catastrophic Risks.”

Abstract: Many global catastrophic and existential risks (X-risks) threaten the existence of humankind. There are also many ideas for their prevention, but the meta-problem is that these ideas are not structured. This lack of structure means it is not easy to choose the right plan(s) or to implement them in the correct order. I suggest using a “Plan A, Plan B” model, which has shown its effectiveness in planning actions in unpredictable environments. In this approach, Plan B is a backup option, implemented if Plan A fails. In the case of global risks, Plan A is intended to prevent a catastrophe and Plan B to survive it, if it is not avoided. Each plan has similar stages: analysis, planning, funding, low-level realization and high-level realization. Two variables—plans and stages—provide an effective basis for classification of all possible X-risks prevention methods in the form of a two-dimensional map, allowing the choice of optimal paths for human survival. I have created a framework for estimating the utility of various prevention methods based on their probability of success, the chances that they will be realized in time, their opportunity cost, and their risk. I also distinguish between top-down and bottom-up approaches.

Throughout human history, doomsayers — people predicting the end of the world — have lived largely on the fringes of society. Today, a doomsday industry is booming thanks to TV shows, movies, hyper-partisan politics and the news media. With the country’s collective anxiety on the rise, even the nation’s wealthiest people are jumping on board, spending millions of dollars on survival readiness in preparation for unknown calamities. We sent Thomas Morton to see how people across the country are planning to weather the coming storm.

Check out VICE News for more: http://vicenews.com

Follow VICE News here:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/vicenews

Twitter: https://twitter.com/vicenews

Tumblr: http://vicenews.tumblr.com/

Instagram: http://instagram.com/vicenews

More videos from the VICE network: https://www.fb.com/vicevideo