In his new book, to be published in September, neuroscientist Francisco Aboitiz links consciousness back to the earliest days of biological life.

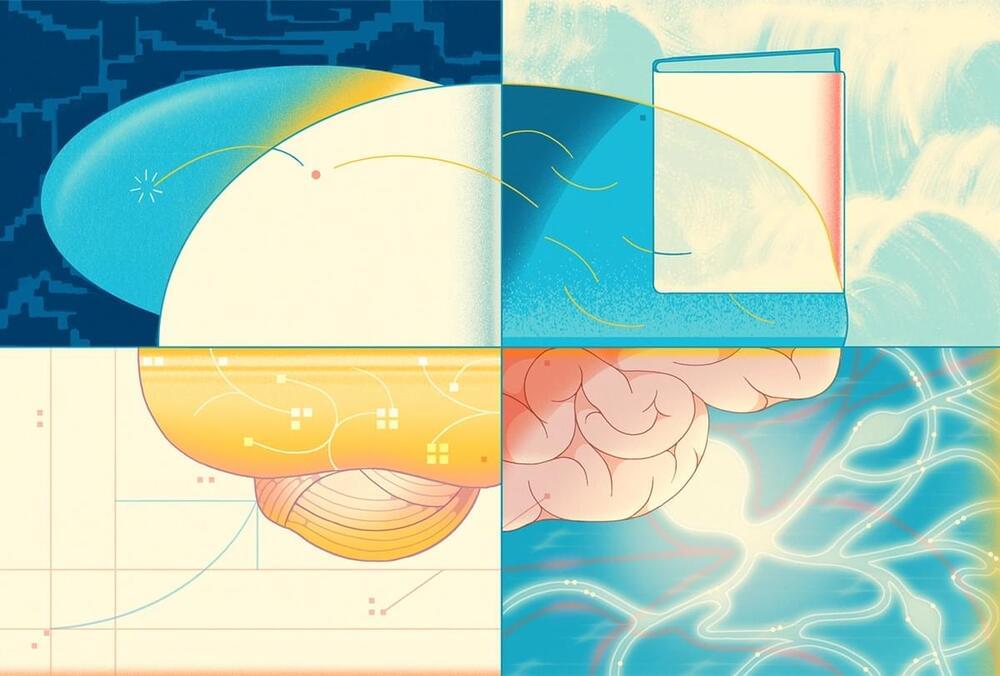

What were galaxies like in the early universe? This is what a recent study published in The Astronomical Journal hopes to address as an international team of researchers investigated the formation and evolution of galaxies in the early universe, as recent studies have suggested they were much larger than cosmology models had simulated. This study holds the potential to help researchers better understand the conditions in the early universe and how life came to be.

“We are still seeing more galaxies than predicted, although none of them are so massive that they ‘break’ the universe,” said Katherine Chworowsky, who is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author of the study.

For the study, the researchers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to peer deep into the universe’s past and observe some of the earliest galaxies to ascertain their sizes and whether they are as massive as recent studies have suggested. After analyzing the data, the researchers discovered that black holes residing at the center of these galaxies are creating false brightness and sizes, meaning these galaxies are much smaller than previously thought, thus reducing the panic within the scientific community regarding cosmological models. However, this study does suggest further research is necessary regarding star formation and evolution within these galaxies.

Berkeley scientists have discovered a new choanoflagellate species in Mono Lake that forms multicellular colonies and hosts a microbiome, offering new perspectives on the evolution of multicellular organisms.

The salty, arsenic-and cyanide-laced waters of the Eastern Sierra Nevada’s Mono Lake is an extremely hostile environment. Aside from the abundant brine shrimp and black clouds of alkali flies, very few organisms live there.

Now, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley have discovered a new creature lurking in the lake’s briny shallows — one that could tell scientists about the origin of animals more than 650 million years ago.

“Those tiny objects with masses comparable to giant planets may themselves be able to form their own planets,” said Dr. Aleks Scholz.

What can rogue planets teach us about the formation and evolution of stars and planets? This is what a recent study published in The Astronomical Journal hopes to address as an international team of researchers investigated NGC 1,333, which is a star-forming cluster located just under 1,000 light-years from Earth. This study holds the potential to help scientists better understand the formation and evolution of stars and planets while challenging previous hypotheses about these processes.

“We are probing the very limits of the star forming process,” said Dr. Adam Langeveld, who is an assistant research scientist at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the study. “If you have an object that looks like a young Jupiter, is it possible that it could have become a star under the right conditions? This is important context for understanding both star and planet formation.”

For the study, the researchers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to observe brown dwarfs that comprise NGC 1,333 in hopes of learning more about how stars form. in the end, the researchers discovered six new rogue planet candidates—officially called free-floating planetary-mass objects (FFPMOs)—with masses ranging between 5–10 Jupiters and that exhibit dusty disks orbiting them. This indicates they are some of the smallest objects formed from processes that are traditionally responsible for creating stars and brown dwarfs, the latter of which never reach appropriate sizes to produce nuclear fusion in their cores.

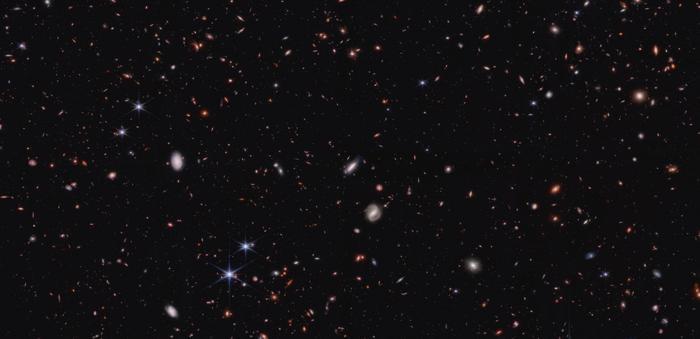

What did NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft on the asteroid moon, Dimorphos, teach astronomers about altering the trajectory of asteroids and asteroids’ formation and evolution? This is what a recent study published in The Planetary Science Journal hopes to address as an international team of researchers investigated the potential geological changes made to Dimorphos, which orbits its parent asteroid, Didymos, when DART impacted the former in September 2022. This study holds the potential to help scientists better understand the formation and evolution of asteroids throughout, and potentially beyond, the solar system, which could hold implications for the early history of the solar system, as well.

“For the most part, our original pre-impact predictions about how DART would change the way Didymos and its moon move in space were correct,” said Dr. Derek Richardson, who is a professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, a DART investigation working group lead, and lead author on the study. “But there are some unexpected findings that help provide a better picture of how asteroids and other small bodies form and evolve over time.”

For the study, the researchers analyzed post-impact data of the DART spacecraft on Dimorphos based on predictions made prior to the impact, which could help in planning for the European Space Agency’s upcoming Hera spacecraft mission to Didymos, which is slated to launch in October 2024 and arrive at Didymos in December 2026. In the end, the researchers found that along with Dimorphos’ orbital parameters being influenced by the impact, its physical shape was altered, as well. This resulted in the small asteroid moon becoming elongated towards its poles, whereas its poles were squished prior to impact. This indicates varying formation and evolutionary processes regarding its geologic composition.

Dark matter remains one of the most enigmatic components of our universe. In this episode of Cosmology 101, we explore the evidence for dark matter and its critical role in shaping the cosmos. From galaxy rotations to cosmic web structures, discover how dark matter’s invisible hand influences the universe’s evolution and our understanding of fundamental physics.

Join Katie Mack, Perimeter Institute’s Hawking Chair in Cosmology and Science Communication, on an incredible journey through the cosmos in our new series, Cosmology 101.

Sign up for our newsletter and download exclusive cosmology posters at: https://landing.perimeterinstitute.ca…

Follow the edge of theoretical physics on our social media:

/ pioutreach.

https://twitter.com/perimeter.

/ perimeterinstitute.

/ perimeter-institute.

Follow our host \.

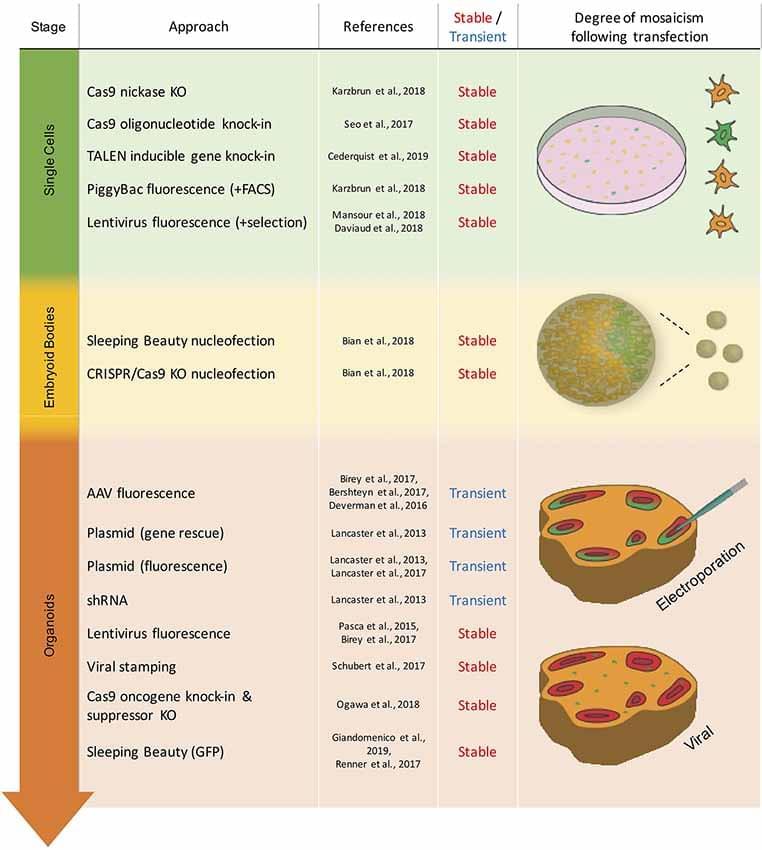

To be able to make full use of these modeling systems, researchers have developed a growing toolkit of genetic modification techniques. These techniques can be applied to mature brain organoids or to the preceding embryoid bodies (EBs) and founding cells. This review will describe techniques used for transient and stable genetic modification of brain organoids and discuss their current use and respective advantages and disadvantages. Transient approaches include adeno-associated virus (AAV) and electroporation-based techniques, whereas stable genetic modification approaches make use of lentivirus (including viral stamping), transposon and CRISPR/Cas9 systems. Finally, an outlook as to likely future developments and applications regarding genetic modifications of brain organoids will be presented.

The development of brain organoids (Kadoshima et al., 2013; Lancaster et al., 2013) has opened up new ways to study brain development and evolution as well as neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain organoids are multicellular 3D structures that mimic certain aspects of the cytoarchitecture and cell-type composition of certain brain regions over a particular developmental time window (Heide et al., 2018). These structures are generated by differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) into embryoid bodies followed by, or combined, with neural induction (Kadoshima et al., 2013; Lancaster et al., 2013). In principle, two different classes of brain organoid protocols can be distinguished, namely: (i) the self-patterning protocols which produce whole-brain organoids; and (ii) the pre-patterning protocols which produce brain region-specific organoids (Heide et al., 2018).

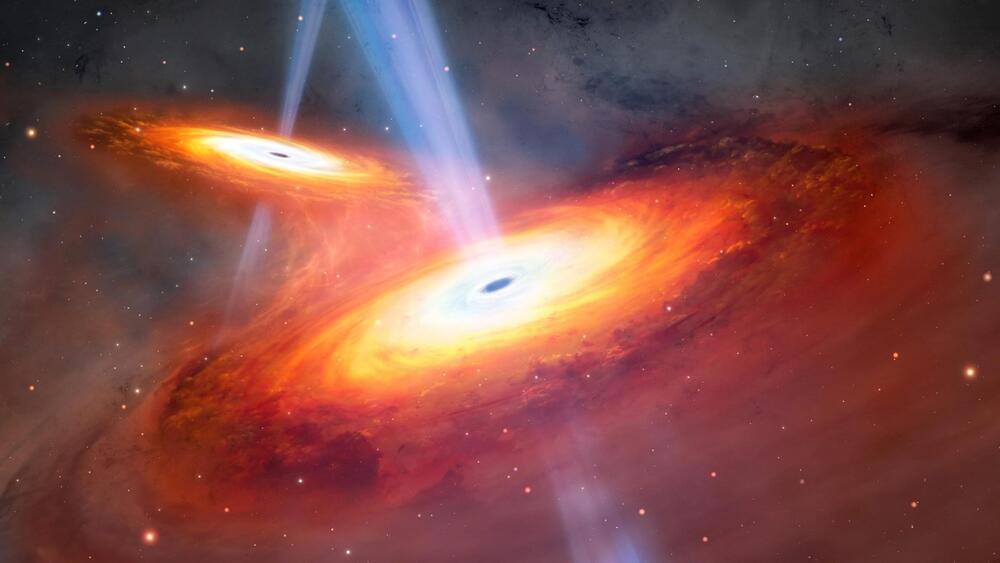

Astronomers have identified the earliest pair of quasars, shining 900 million years post-Big Bang, revealing insights into galaxy mergers and the reionization era of the Universe.

An international team of astronomers, including members from the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU, WPI), has discovered the earliest known pair of quasars using the Subaru Telescope and Gemini North telescope, both situated on Maunakea in Hawai’i. These quasars, powered by actively feeding supermassive black holes, emit intense radiation. This significant discovery will provide insights into the early evolution of the Universe.

About 400 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang, something, possibly a combination of sources, unleashed enough radiation to strip the electrons from most of the hydrogen atoms, completely altering the nature of the Universe. Quasars are one potential source of the radiation that caused this “reionization” of the Universe. When matter falls into the supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, the matter heats up and releases radiation in a phenomenon known as a quasar.

The Earth’s rotation has been decelerating throughout its history due to tidal dissipation, but the variation of the rate of this deceleration through time has not been established. We present a detailed analysis of eight geological datasets to constrain the Earth’s rotational history from 650 to 240 Mya. The results allow us to test physical tidal models and point to a staircase pattern in the Earth’s deceleration from 650 to 280 Mya. During this time interval, the Earth–Moon distance increased by approximately 20,000 km and the length of day increased by approximately 2.2 h. Specifically, there are two intervals with high Earth rotation deceleration, 650 to 500 Mya and 350 to 280 Mya, separated by an interval of stalled deceleration from 500 to 350 Mya. The interval with stalled deceleration is attributed mainly to reduced tidal dissipation due to the continent-ocean configuration at the time, not to changes in Earth’s dynamical ellipticity from continental assembly or glaciation. Modeling indicates that, except for the very recent time, tidal dissipation is the main driver for decelerating Earth rotation. One potential implication of our findings is that the Earth’s tidal dissipation, along with Earth’s rotation deceleration, may play a role in the evolving Earth.