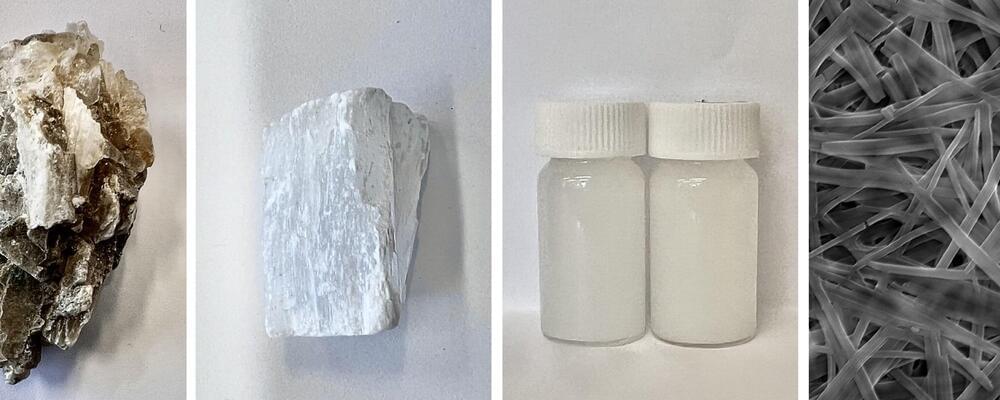

Scientists have discovered a new class of materials, carbon nitrides, which could rival diamonds in hardness. This discovery, the result of international collaboration and decades of research, opens up possibilities for various industrial applications due to their durability and other properties like photoluminescence and high energy density. Funded by international grants and published in Advanced Materials, this breakthrough marks a significant advancement in material science.

Scientists have solved a decades-long puzzle and unveiled a near unbreakable substance that could rival diamond, as the hardest material on earth, a study says.

Researchers found that when carbon and nitrogen precursors were subjected to extreme heat and pressure, the resulting materials – known as carbon nitrides – were tougher than cubic boron nitride, the second hardest material after diamond.