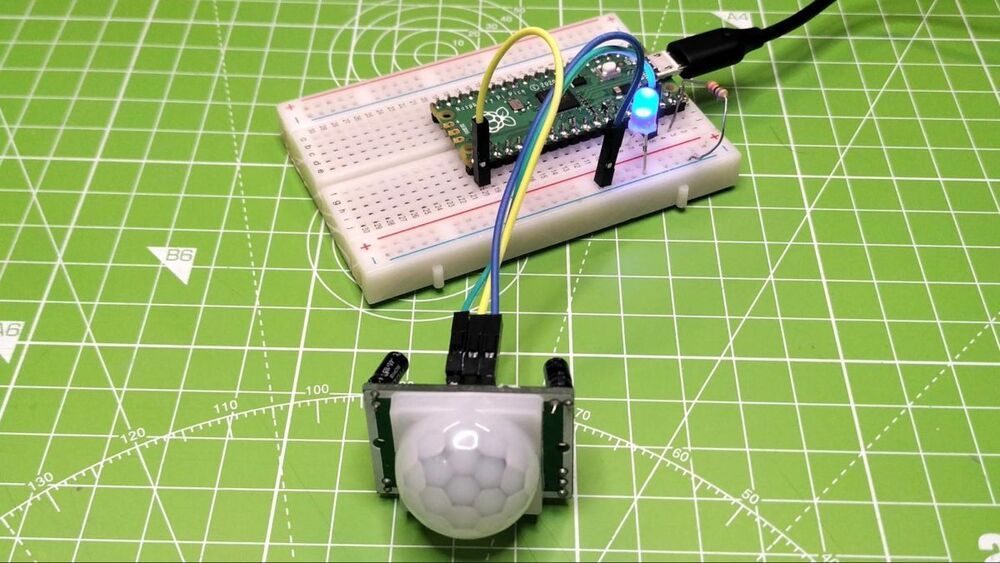

“The Murakami Corporation has partnered with Parity Innovations, a startup that developed a holographic display technology, the Parity Mirror, which breaks up a projected image using a series of tiny mirrors and then refocuses them into a reconstituted image that appears to float in mid-air. What the Murakami Corporation brings to the table is its infrared sensors, which are able to detect the presence of fingers without them having to make physical contact. The result is a series of glowing buttons that don’t actually exist but can still be activated by touching them.”

Japanese smart toilets already provide a luxe experience, but this high-tech upgrade will take them to the next level.