The suit relies on kinetic energy from the user to mirror every move they make. In a demo held at Haneda Innovation City, a man demonstrated some of what the suit is capable of.

The Force was strong in him. One of Enzo Romero’s favorite activities is playing the guitar, which he effortlessly does with his bright blue hand. Initially, it used to hurt, as he used his handless right arm to press down on chords. But now, with fingers on the end, he can play music painlessly.

Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back, marketed as simply The Empire Strikes Back, is a 1980 film directed by Irvin Kershner and written by Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan from a story by George Lucas. It is the second part of the Star Wars original trilogy.

The film concerns the continuing struggles of the Rebel Alliance against the Galactic Empire. During the film, Han Solo, Chewbacca, and Princess Leia Organa are being pursued across space by Darth Vader and his elite forces. Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker begins his major Jedi training with Yoda, after an instruction from Obi-Wan Kenobi’s spirit. In an emotional and near-fatal confrontation with Vader, Luke is presented with a horrific revelation and must face his destiny.

Though controversial upon release, the film has proved to be the most popular film in the series among fans and critics and is now widely regarded as one of the best sequel films of all time, as well as one of the greatest films of all time. It was re-released with changes in 1997 and on DVD in 2004. The film was re-released on Blu-ray format in September of 2011. A radio adaptation was broadcast on National Public Radio in the U.S.A. in 1983. The film was selected in 2010 to be preserved by the Library of Congress as part of its National Film Registry.

The researchers were inspired by actual skin. Researchers have been working on robot dexterity for several years now trying to give the machines human-like sensitivity. This has been no easy task as even the most advanced machines struggle with this concept.

Now the team is working on making the artificial fingertip as sensitive to fine detail as the real thing. Currently, the 3D-printed skin is thicker than real skin which may be hindering this process. As such, Lepora’s team is now working on 3D-printing structures on the microscopic scale of human skin.

“Our aim is to make artificial skin as good – or even better — than real skin,” concluded Professor Lepora. The end result could have many applications in soft robotics including in the Metaverse.

R/IntelligenceSupernova — dedicated to techno-optimists, singularitarians, transhumanist thinkers, cosmists, futurists, AI researchers, cyberneticists, crypto enthusiasts, VR creators, artists, philosophers of mind. Accelerating now towards the Cybernetic Singularity with unprecedented advances in AI & Cybernetics, VR, Biotechnology, Nanotechnology, Bionics, Genetic Engineering, Optogenetics, Neuroengineering, Robotics, and other IT fields.

Join now: https://www.reddit.com/r/IntelligenceSupernova.

#Subreddit #IntelligenceSupernova

An advanced bionic arm can be life-changing for a person with an upper limb amputation. But in India, with a population of nearly 1.4 billion and average income of just $2,000 a year, advanced prosthetics are financially out of reach for many amputees.

So the Indian startup Makers Hive developed one that’s not only 90% cheaper, but also more functional.

Advanced prosthetics: A bionic arm contains sensors that press against the skin of the wearer’s residual limb to detect electrical signals from their nerves.

The 3D-printed, lightweight KalArm is the result of those efforts. It features 16 grips, customizable panels, and a companion app, which can be used to monitor the arm’s performance, as well as install firmware updates.

Indian startup Makers Hive has developed a bionic arm that’s not only 90% cheaper than most, but also more functional.

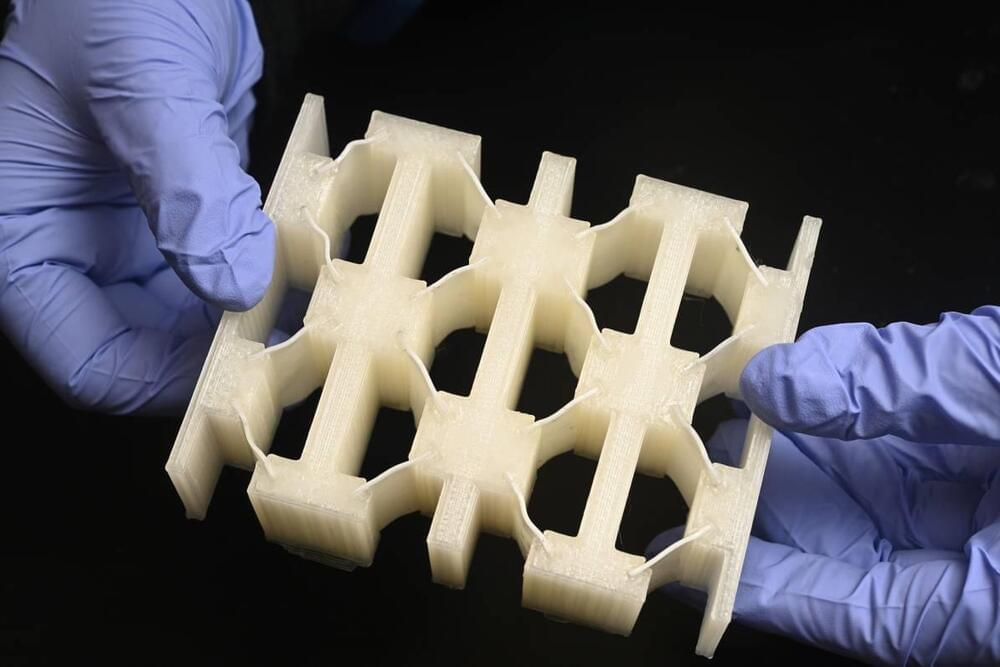

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have developed a new shock-absorbing material that is super lightweight, yet offers the protection of metal. The stuff could make for helmets, armor and vehicle parts that are lighter, stronger and, importantly, reusable.

The key to the new material is what are known as liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs). These are networks of elastic polymers in a liquid crystalline phase that give them a useful combination of elasticity and stability. LCEs are normally used to make actuators and artificial muscles for robotics, but for the new study the researchers investigated the material’s ability to absorb energy.

The team created materials that consisted of tilted beams of LCE, sandwiched between stiff supporting structures. This basic unit was repeated over the material in multiple layers, so that they would buckle at different rates on impact, dissipating the energy effectively.

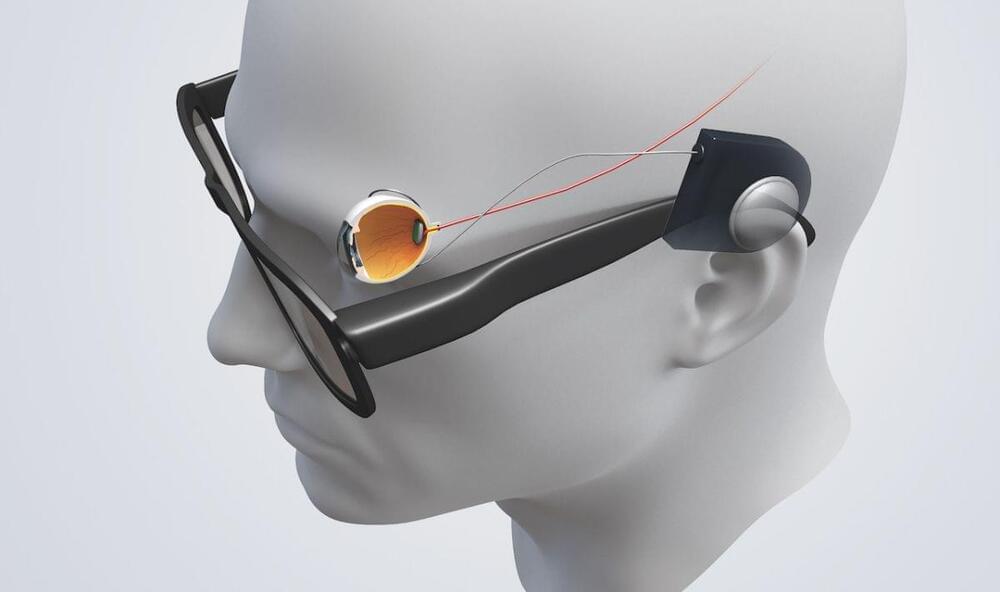

This technology has to translate images into something the human brain can understand. Click the numbers in the interactive image below to find read about how this works.

There are a whole range of conditions, some which are picked up due to the aging process and others which may be inherited, that can cause sight deterioration.

Bionic eyes work by ‘filling in the blanks’ between what the retina perceives and how it is processed in the brain’s visual cortex, that breakdown occurs in conditions which impact the retina. It is largely these conditions which bionic eyes could help treat.

http://www.homomimeticus.eu/

Part of the ERC-funded project Homo Mimeticus, the Posthuman Mimesis conference (KU Leuven, May 2021) promoted a mimetic turn in posthuman studies. In the first keynote Lecture, Prof. Kevin Warwick (U of Coventry) argued that our future will be as cyborgs – part human, part technology. Kevin’s own experiments will be used to explain how implant and electrode technology can be employed to create cyborgs: biological brains for robots, to enable human enhancement and to diminish the effects of neural illnesses. In all cases the end result is to increase the abilities of the recipients. An indication is given of a number of areas in which such technology has already had a profound effect, a key element being the need for an interface linking a biological brain directly with computer technology. A look will be taken at future concepts of being, for posthumans this possibly involving a click and play body philosophy. New, much more powerful, forms of communication will also be considered.

HOM Videos is part of an ERC-funded project titled Homo Mimeticus: Theory and Criticism, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement n°716181)

Follow HOM on Twitter: https://twitter.com/HOM_Project.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/HOMprojectERC