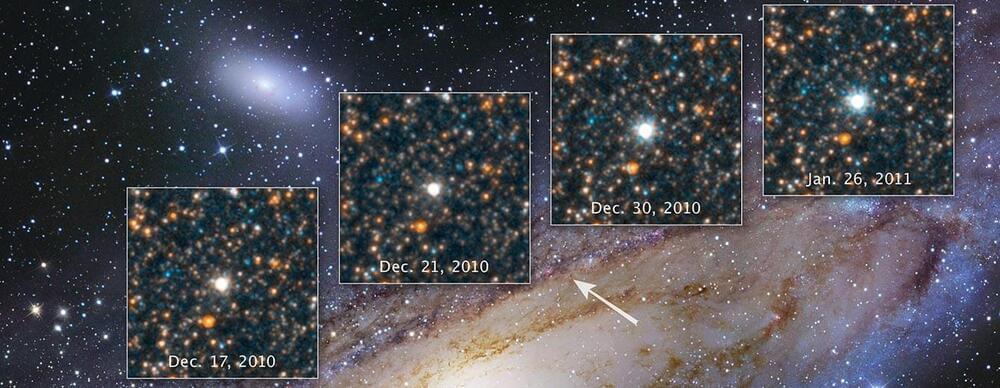

Across cosmic history, powerful forces have acted on matter, reshaping the universe into an increasingly complex web of structures. Now, new research led by Joshua Kim and Mathew Madhavacheril at the University of Pennsylvania and their collaborators at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests our universe has become “messier and more complicated” over the roughly 13.8 billion years it’s been around, or rather, the distribution of matter over the years is less “clumpy” than it should be expected.

“Our work cross-correlated two types of datasets from complementary, but very distinct, surveys,” says Madhavacheril, “and what we found was that, for the most part, the story of structure formation is remarkably consistent with the predictions from Einstein’s gravity. We did see a hint for a small discrepancy in the amount of expected clumpiness in recent epochs, around four billion years ago, which could be interesting to pursue.”

The data, which was published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics and the preprint server arXiv, comes from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope’s (ACT) final data release (DR6) and the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument’s (DESI) Year 1.