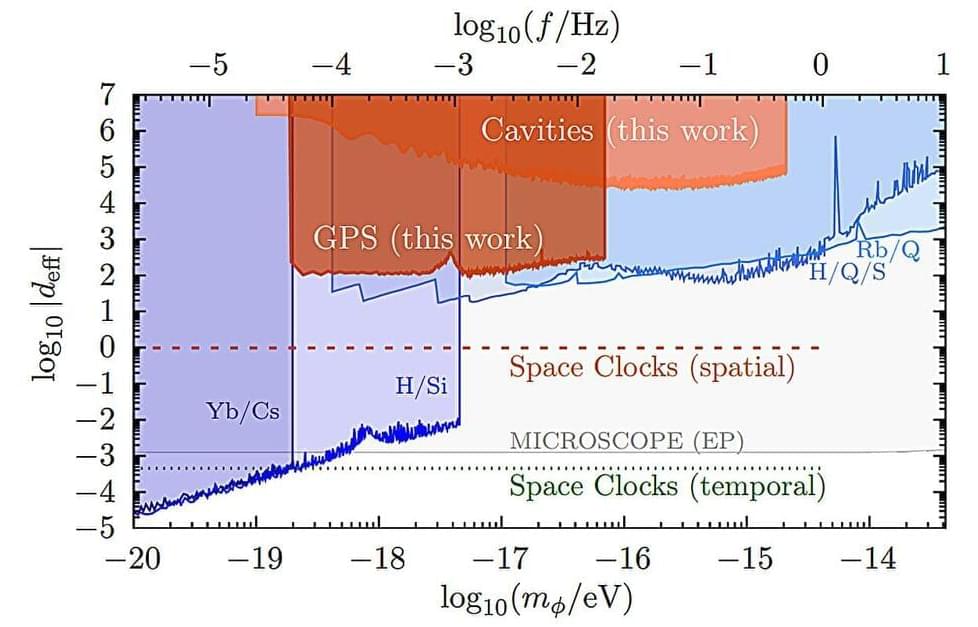

A team of international researchers has developed an innovative approach to uncover the secrets of dark matter. In a collaboration between the University of Queensland, Australia, and Germany’s metrology institute (Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, PTB), the team used data from atomic clocks and cavity-stabilized lasers located far apart in space and time to search for forms of dark matter that would have been invisible in previous searches.

This technique will allow the researchers to detect signals from dark matter models that interact universally with all atoms, an achievement that has eluded traditional experiments.

The team analyzed data from a European network of ultra-stable lasers connected by fiber optic cables (previously reported in a 2022 article), and from the atomic clocks aboard GPS satellites. By comparing precision measurements across vast distances, the analysis became sensitive to subtle effects of oscillating dark matter fields that would otherwise cancel out in conventional setups.