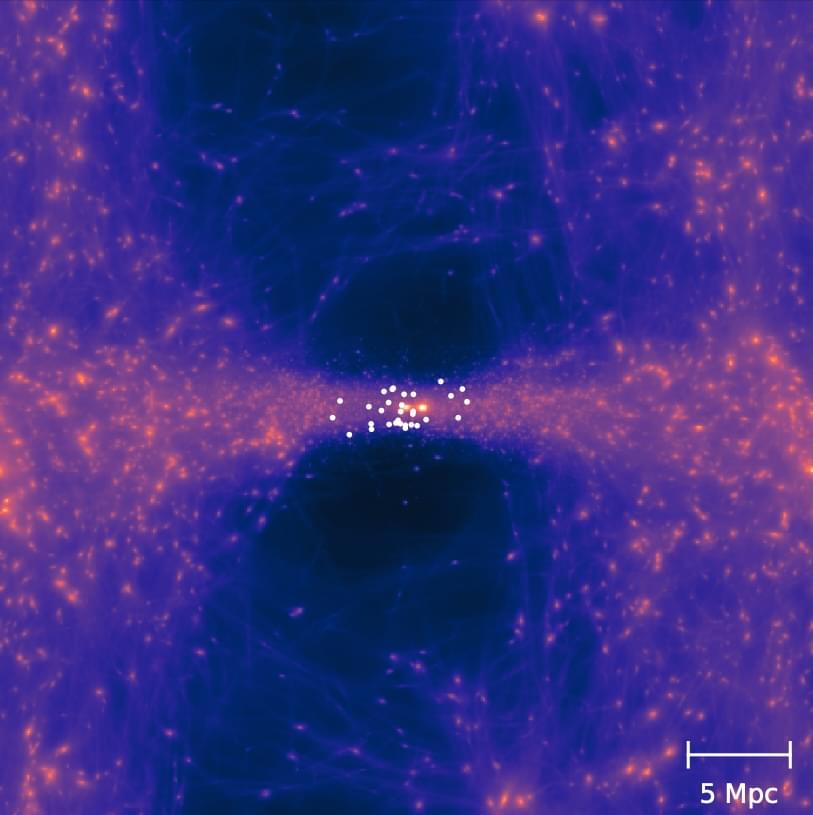

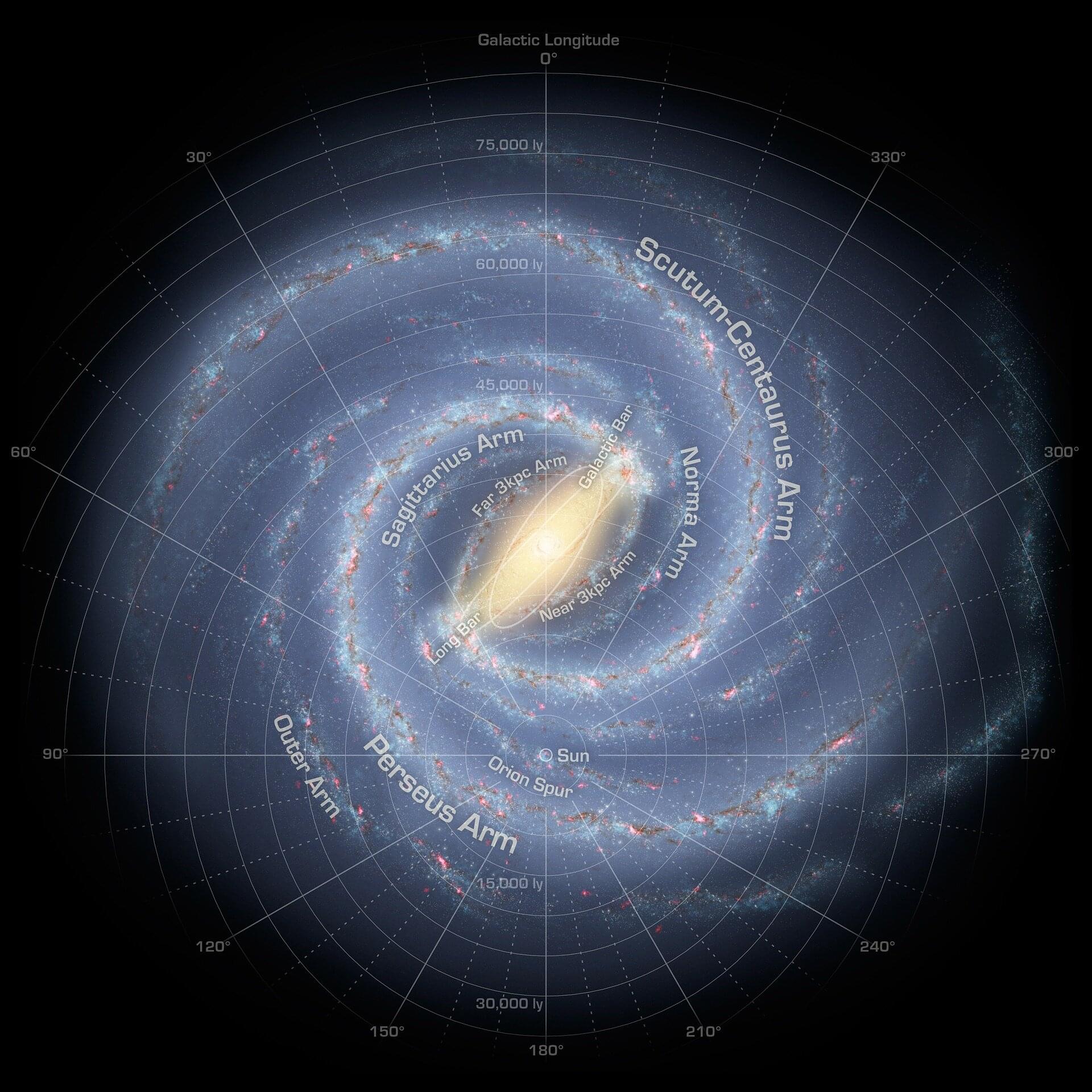

Computer simulations carried out by astronomers from the University of Groningen in collaboration with researchers from Germany, France and Sweden show that most of the (dark) matter beyond the Local Group of galaxies (which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy) must be organised in an extended plane. Above and below this plane are large voids. The observed motions of nearby galaxies and the joint masses of the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy can only be properly explained with this ‘flat’ mass distribution. The research, led by PhD graduate Ewoud Wempe and Professor Amina Helmi, was published today in Nature Astronomy.

Almost a century ago, astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that virtually all galaxies are moving away from the Milky Way. This is important evidence for the expansion of the universe and for the Big Bang. But even in Hubble’s time, it was clear that there were exceptions. For example, our neighbouring galaxy, Andromeda, is moving towards us at a speed of about 100 kilometres per second.

In fact, for half a century, astronomers have been wondering why most large nearby galaxies – with the exception of Andromeda – are moving away from us and do not seem to be affected by the mass and gravity of the so-called Local Group (the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy and dozens of smaller galaxies).