An old theory of dark matter may be gaining ground thanks to new analysis of LIGO’s historic gravitational wave discovery.

A new study published in Nature presents one of the most complete models of matter in the universe and predicts hundreds of massive black hole mergers each year observable with the second generation of gravitational wave detectors.

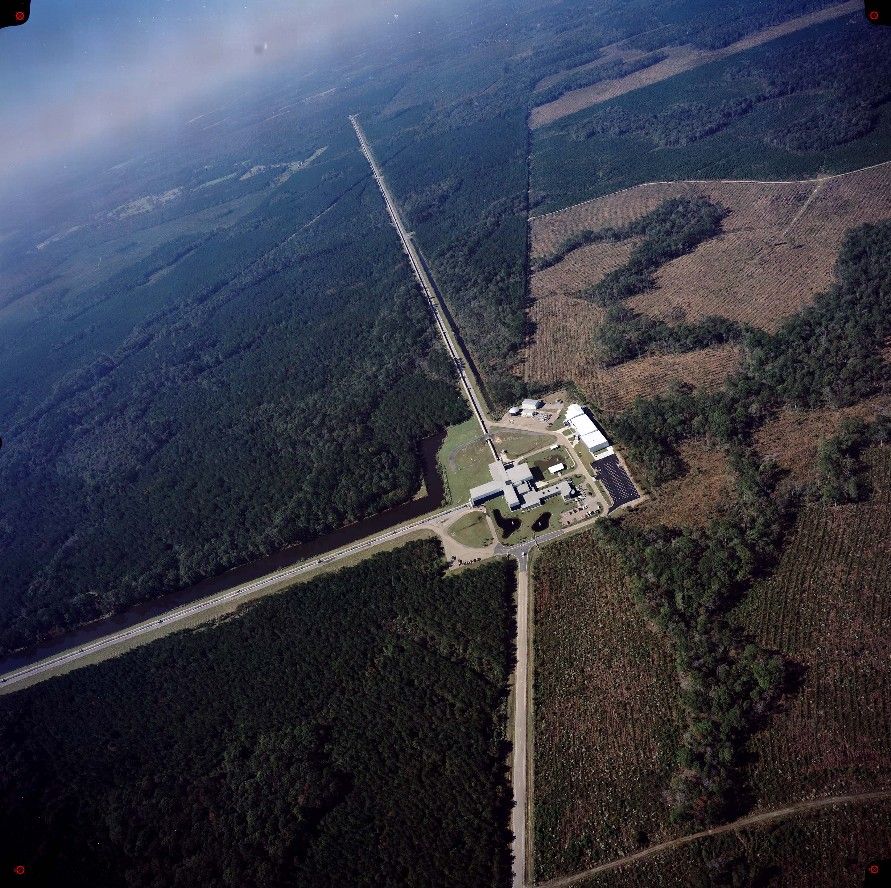

The model anticipated the massive black holes observed by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory. The two colliding masses created the first directly detected gravitational waves and confirmed Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

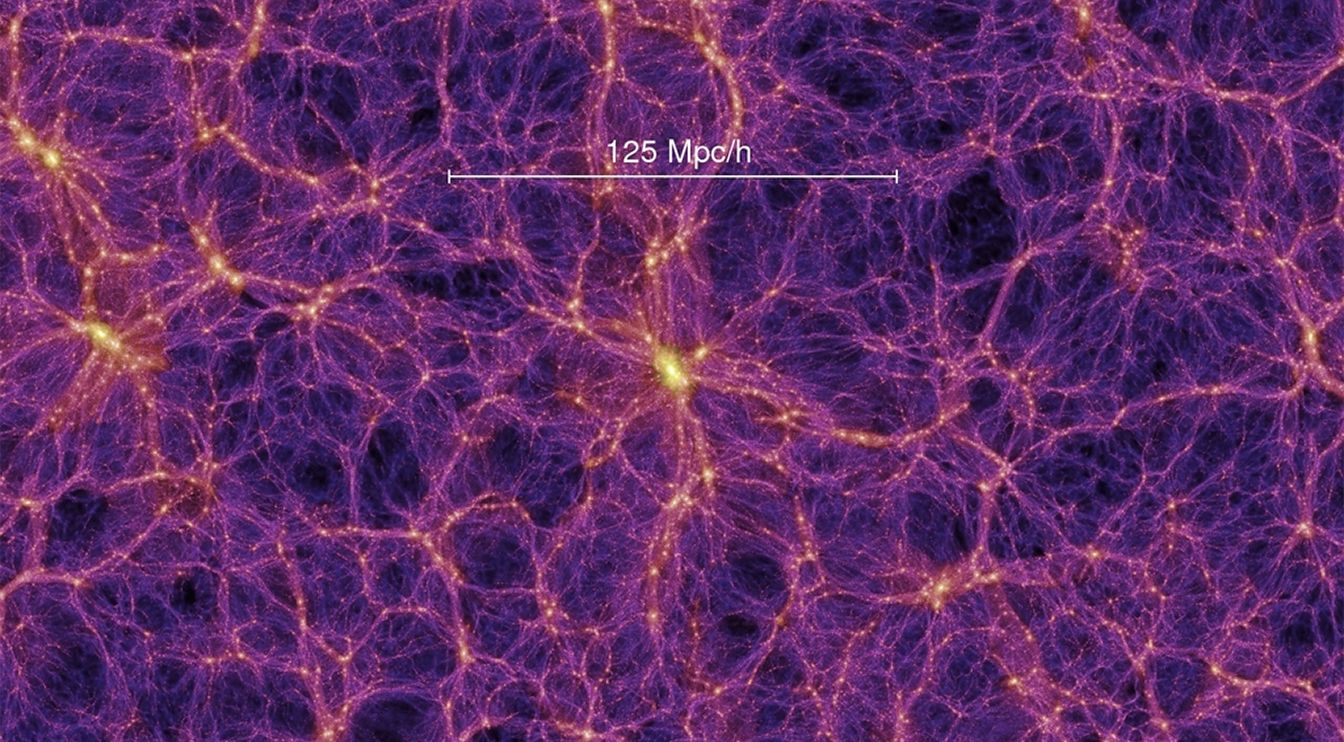

“The universe isn’t the same everywhere,” said Richard O’Shaughnessy, assistant professor in RIT’s School of Mathematical Sciences, and co-author of the study led by Krzysztof Belczynski from Warsaw University. “Some places produce many more binary black holes than others. Our study takes these differences into careful account.”

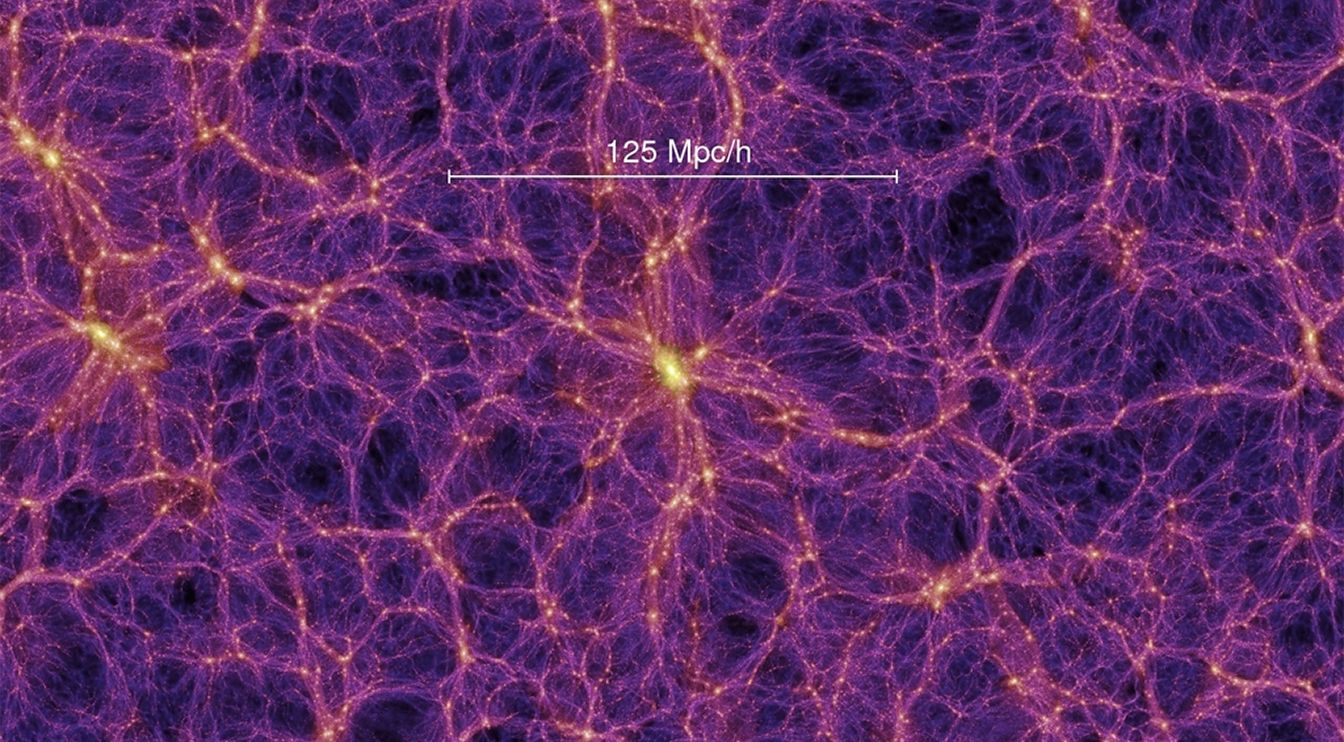

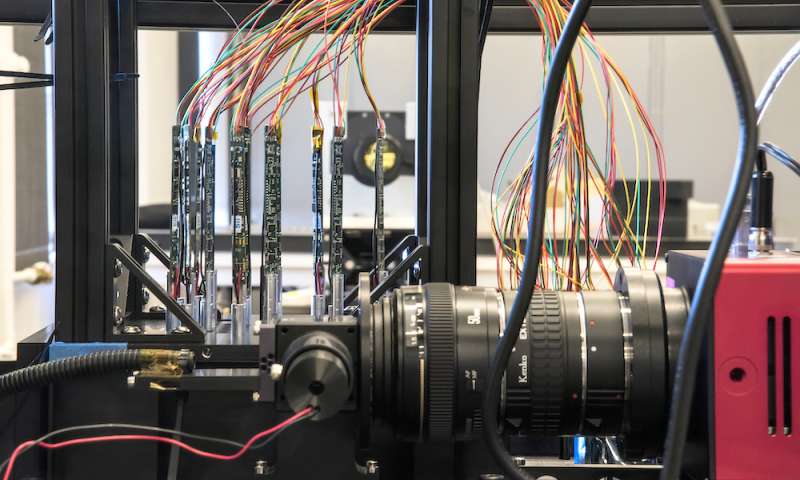

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Australian National University have developed new technology that aims to make the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) even more sensitive to faint ripples in space-time called gravitational waves.

Scientists at Advanced LIGO announced the first-ever observation of gravitational waves earlier this year, a century after Albert Einstein predicted their existence in his general theory of relativity. Studying gravitational waves can reveal important information about cataclysmic astrophysical events involving black holes and neutron stars.

In The Optica l Society’s journal for high impact research, Optica, the researchers report on improvements to what is called a squeezed vacuum source. Although not part of the original Advanced LIGO design, injecting the new squeezed vacuum source into the LIGO detector could help double its sensitivity. This would allow detection of gravitational waves that are far weaker or that originate from farther away than is possible now.

Dr Alexander Tchekhovskoy from the University of California, Berkeley and Dr Omer Bromberg from Hebrew University came up with a simulation demonstrating the powerful jets generated by supermassive black holes at the centres of the largest galaxies.

The simulation explains why some black holes burst forth as bright beacons visible across the universe, while others fall apart and never pierce the halo of the galaxy.

One tenth of all galaxies with active nuclei, presumed to have supermassive black holes, have jets of gas spurting in opposite directions from the core.

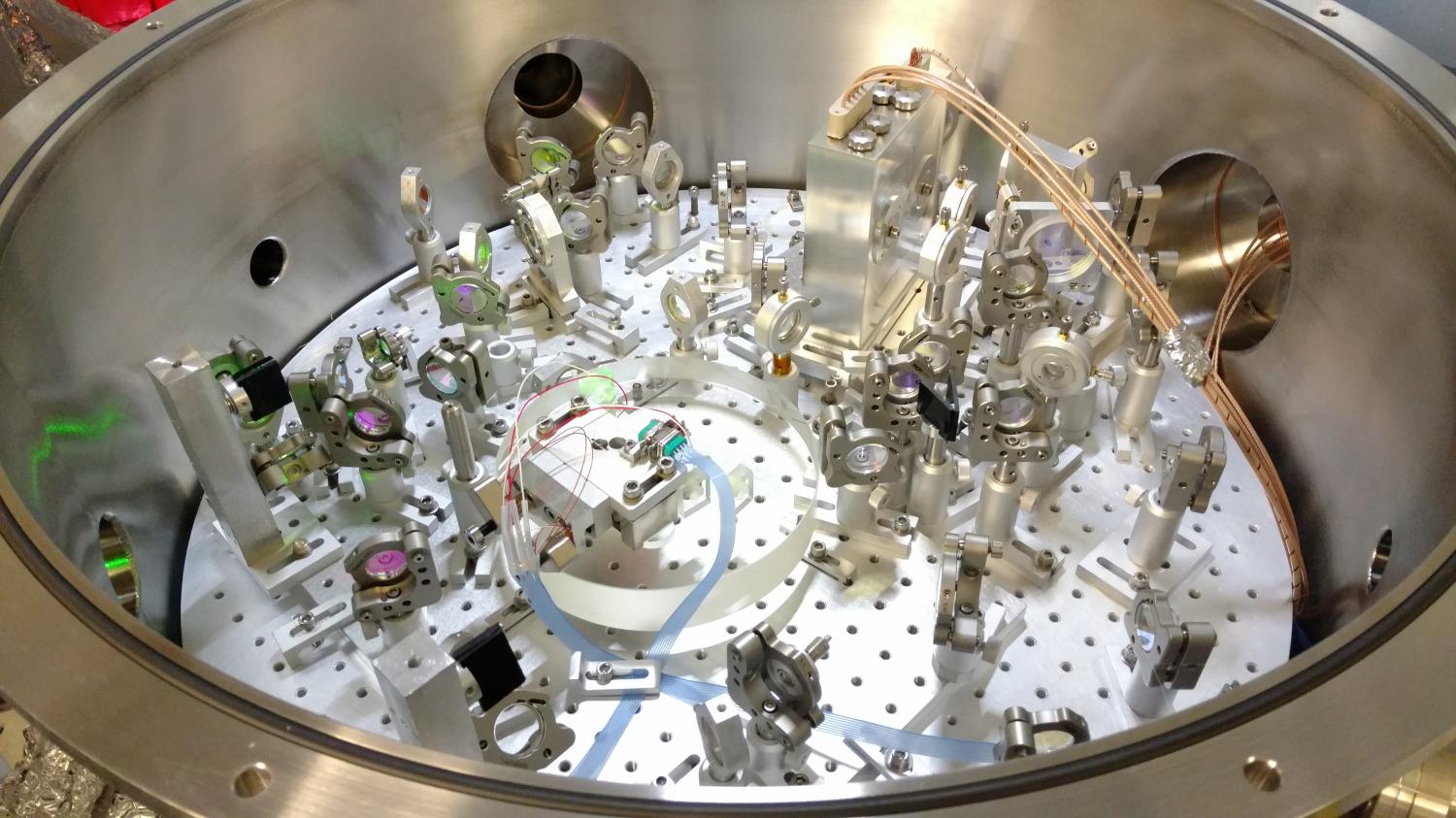

Physicists have come up with a new way to predict what lies beyond the event horizon of a black hole, and it could give us a more accurate idea of their mysterious internal structures.

Thanks to the first — and now second — direct observation of gravitational waves emanating from what scientists think are black hole mergers, we’re starting to get our first real evidence that black holes do actually exist in reality, not just theory.

But even if we can prove they really do physically exist, there’s no getting around the fact that, thanks to their enormous gravitational pull, black holes swallow up anything that falls beyond their event horizon.

When an astronomical observatory detected two black holes colliding in deep space, scientists celebrated confirmation of Einstein’s prediction of gravitational waves. A team of astrophysicists wondered something else: Had the experiment found the “dark matter” that makes up most of the mass of the universe?

The eight scientists from the Johns Hopkins Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy had already started making calculations when the discovery by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) was announced in February. Their results, published recently in Physical Review Letters, unfold as a hypothesis suggesting a solution for an abiding mystery in astrophysics.

“We consider the possibility that the black hole binary detected by LIGO may be a signature of dark matter,” wrote the scientists in their summary, referring to the black hole pair as a “binary.” What follows are five pages of annotated mathematical equations showing how the researchers considered the mass of the two objects LIGO detected as a point of departure, suggesting that these objects could be part of the mysterious substance known to make up about 85 percent of the mass of the universe.

Scientists have seen two black holes crash into each other and merge for the second time, proving Albert Einstein was right and showing the first observation was no fluke.

Ultra-sensitive instruments called the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected the ripple in gravitational waves that came across space and time to Earth last December, the team reported Wednesday.

LIGO detects gravitational waves for the second time, from another pair of merging black holes. This time they were smaller and provided a longer-duration signal of their final moments. Two events within four months suggests that such detections will soon be giving astronomers a wealth of new information about previously invisible events in the Universe.

“A prototype system, designed as a test for a planned array of 5,000 galaxy-seeking robots, is taking shape at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).”