Professor Stephen Hawking might have died before the James Webb Space Telescope finally launched. Still, due to the vast space legacy of the late physicist, many hours of the new space telescope will be dedicated to proving some of his theories! One of such theories is the very last one Hawking worked on before his death, in which he argued about a multiverse theory that implies an exact copy of you existed in a parallel universe! What is the multiverse theory, and will the James Webb Space Telescope finally prove Stephen Hawking’s multiverse theory?

Stephen Hawking died in 2018, missing the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope by more than three and a half years. That was thanks to multiple delays that pushed the launch date from between 2007 and 2011. It also gulped about 10 billion dollars, about ten times the initial budget. However, following a successful launch and deployment of its components, this powerful space telescope will undergo several months of calibrating and testing before settling down to work.

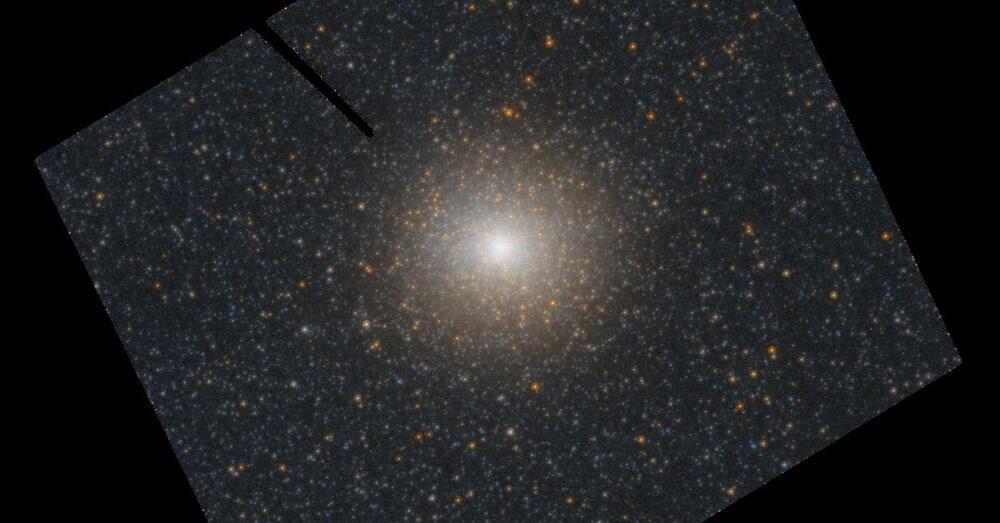

Thanks to the large 6.5 meter giant mirror that had to be folded during launch, the telescope will be able to peer into the atmospheres of planets outside our Solar System and peek through massive clouds of dust to watch the birth of new stars and planetary systems. JWST will be able to gather and reflect light from the early Universe. The Universe is thought to be around 13.8 billion years old, and JWST will be able to observe light from the earliest stars and galaxies, close to the Big Bang!

The JWST is an infrared telescope, meaning it uses infrared radiation to detect objects in space. It is able to observe celestial bodies, such as stars, nebulae, and planets that are too cool or too faint to be observed in visible light, that is, what is visible to the human eye. According to NASA, infrared radiation can also pass through gas and dust, which appear opaque to the human eye. This is different from the world-famous Hubble Telescope, which sees visible light, ultraviolet radiation, and near-infrared radiation. In order for the instruments aboard to work, they need to be kept at extremely cold temperatures,-370 degrees Fahrenheit or lower. The large sunshield protects the telescope from the heat of the sun and keeps the instruments cold.

According to a report conducted by an independent review board in 2018, there were 344 “single-point failures,” or steps that needed to work for the mission to succeed! However, the telescope was tucked inside the nose of an Ariane 5 rocket and launched safely from the European Space Agency’s Spaceport in French Guiana in December last year! It separated from the rocket after the launch and began unfolding. According to NASA, about 30 minutes after the launch, the first deployment took place as the solar panels unfolded so the telescope could get power from the sun!

Because of JWST’s capabilities, many astronomers are vying for time with the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute, which oversees science operations on Hubble and JWST, had sent out a call to astronomers for proposals on how they’d like to use James Webb, with 6,000 hours of observation time up for grabs! The lucky ones have now received approvals for their projects, and we look forward to the wealth of knowledge they will enrich us with! There is plenty of time for the JWST to unlock the deep secrets of the Universe, with about 20 years of operation guaranteed by the amount of fuel aboard the space telescope.

With the JWST safely delivered to its location about one million miles away from the earth, is it time to confirm one of Hawking’s most intriguing theories, the multiverse concept? The theory is special because it was the last one published by the professor! In fact, that final research from the sharp mind was submitted for publication just ten days before his death!

In the paper, titled “A smooth exit from eternal inflation?” which he co-authored with Thomas Hertog, a physicist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, Hawking laid out a theory on the origin of the Universe that might settle a few lingering questions. However, despite being his last work, the paper was actually a final look at one of his earliest theories. In fact, if the JWST eventually helps prove the existence of the multiverse, it will make the scientists behind it likely candidates for a Nobel Prize! However, since Nobel Prizes cannot be awarded posthumously, Hawking would be ineligible to receive it.

Category: cosmology – Page 314

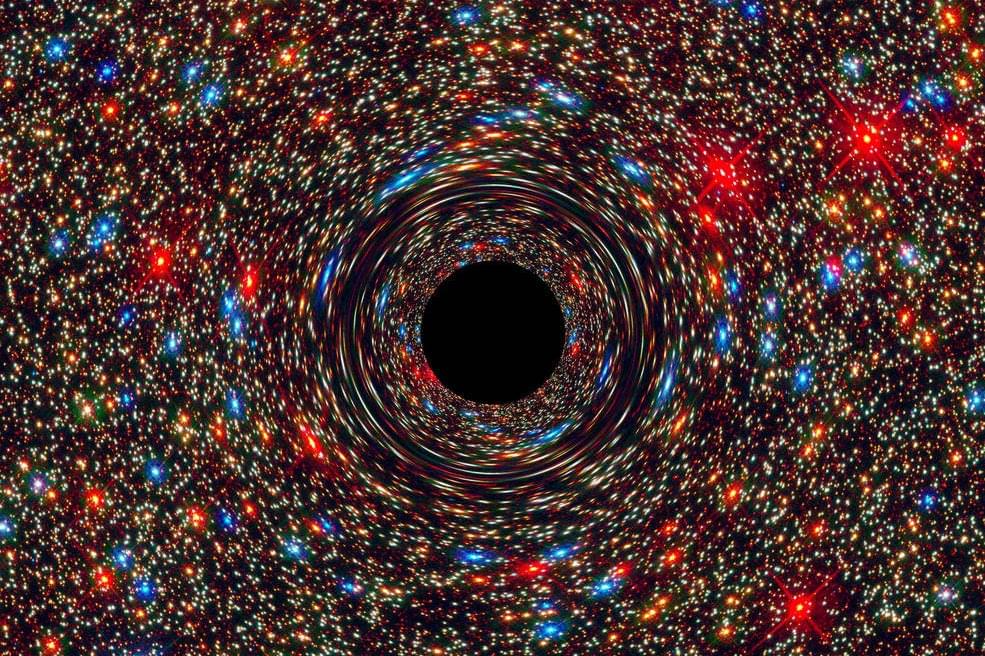

Astronomers are gearing up for never-before-seen merger between two black holes

A team of astronomers noted a binary pair of black holes that may be on the verge of merging. The event could provide an unprecedented observing opportunity.

Observing more disk galaxies than theory allows

The Standard Model of Cosmology describes how the universe came into being according to the view of most physicists. Researchers at the University of Bonn have now studied the evolution of galaxies within this model, finding considerable discrepancies with actual observations. The University of St. Andrews in Scotland and Charles University in the Czech Republic were also involved in the study. The results have now been published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Most galaxies visible from Earth resemble a flat disk with a thickened center. They are therefore similar to the sports equipment of a discus thrower. According to the Standard Model of Cosmology, however, such disks should form rather rarely. This is because in the model, every galaxy is surrounded by a halo of dark matter. This halo is invisible, but exerts a strong gravitational pull on nearby galaxies due to its mass. “That’s why we keep seeing galaxies merging with each other in the model universe,” explains Prof. Dr. Pavel Kroupa of the Helmholtz Institute for Radiation and Nuclear Physics at the University of Bonn.

This crash has two effects, the physicist explains: “First, the galaxies penetrate in the process, destroying the disk shape. Second, it reduces the angular momentum of the new galaxy created by the merger.” Put simply, this greatly decreases its rotational speed. The rotating motion normally ensures that the centrifugal forces acting during this process cause a new disk to form. However, if the angular momentum is too small, a new disk will not form at all.

The Omega Singularity: The Cosmological Projector of All Possible Timelines

E verything is Code. Immersive [self-]simulacra. We all are waves on the surface of eternal ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness in motion, self-referential creative divine force expressing oneself in an exhaustible variety of forms and patterns throughout the multiverse of universes. “I am” the Alpha, Theta & Omega – the ultimate self-causation, self-reflection and self-manifestation instantiated by mathematical codes and projective fractal geometry.

In my new volume of The Cybernetic Theory of Mind series – The Omega Singularity: Universal Mind & The Fractal Multiverse – we discuss a number of perspectives on quantum cosmology, computational physics, theosophy and eschatology. How could dimensionality be transcended yet again? What is the fractal multiverse? Is our universe a “metaverse” in a universe up? What is the ultimate destiny of our universe? Why does it matter to us? What is the Omega Singularity?

Photographer Captures James Webb Space Telescope Traveling to Orbit

Astrophotographer Jason Guenzel managed to capture the James Webb Space Telescope on its journey while it was 1 million kilometers away.

$323 million in ETH stolen from cross-chain protocol Wormhole

Ben RayfieldWeather control tech exists, to some extent. EMP weapons exist. If there was a 477 mile long lightning, it was probably either due to the sun or is a weapon or a terraforming experiment.

Quinn SenaAuthor.

GIPHY

Genevieve Klien shared a link.

According to a series of etherscan transactions, an attacker has exploited Wormhole, a bridge between the Ethereum and Solana blockchains, for close to $323 million in ETH.

Wormhole is a bridging protocol that enables assets to move across various blockchain protocols. When a user sends assets from one chain to another, the bridge locks the assets and mints a wrapped version of the funds on the destination chain.

Is spacetime a quantum code?

In 2014, physicists found evidence of a deep connection between quantum error correction and the nature of space, time and gravity. Generally, gravity is defined as the fabric of space and time but beyond Einstein’s theory, there must be a quantum origin from which the space-time somehow emerges.

The three physicists at the origin of this discovery, Ahmed Almheiri, Xi Dong and Daniel Harlow, suggested that a holographic “emergence” of space-time works just like a quantum error-correcting code. In their paper “Bulk Locality and Quantum Error Correction in AdS/CFT” published in its first version in November 2014, they showed that space-time emerges from this quantum error correction code in an anti-de Sitter (AdS) universes.

The discovery is opening a new way to capture more properties of space-time.